There has been a great deal of ink spilled about antisemitism among Muslims in the last few months since the Hamas attack on southern Israel. This prompted me to pick up the threads of a post I started writing a few years ago, about the history of relations between Jews and Islam since its emergence in 7th century Arabia. I had grown up with the notion of some intractable religious/ideological dispute or inexplicable hatred between Jews and Muslims seared into my mind by the news media and popular culture. When I started researching this subject years ago I was surprised to learn that this was not the case, that this specific animosity (such as it is) is mainly a 20th century phenomenon. Given that systematic persecution of Jews was largely a European phenomenon, culminating in the horrors of the Nazi Holocaust, it has also been somewhat galling to see Europeans lecturing Arabs on antisemitism.

Germans in particular have been unstinting in their support for Israel’s genocidal campaign of revenge against Gaza’s population as a whole, which has to date (early April 2024) taken the lives of over 32,000 victims, the vast majority of them innocent civilians, women and children. This pontificating seems weird to me, given their past. Much of the current racist discourse dominating the public sphere in Germany is accompanied by empty sloganeering. It seems to me that many of the people behind the ‘Nie Wieder Ist Jetzt : Never Again is Now’ mantra are the ones cheering ‘it’ on…again. How can so many educated, apparently-reasonable people not merely countenance this doublethink with a straight face, but actively advocate it? Partly because they are not as educated and reasonable as they imagine themselves to be. Because a profound distortion of historical truth has been taking shape in the western imagination in recent years, in which antisemitism is primarily seen as a Muslim phenomenon, with the Christian west seeing itself as the defenders of Jews/Israel (the two are often, dangerously, conflated). Not to labour the point, but given the terrible things European societies inflicted upon Jews over more than a millennium, and how deep-rooted antisemitism has been in Christian European culture (by no means confined to Germany) this seems a grotesque distortion and reason enough to look at the matter from a historical perspective, with the focus as much as possible on bald historical facts rather than what we would like to believe.

I also thought it would be good to combine a more general short history of Jews as a minority in Muslim lands with a more focused, local study of Jews in Palestine up until the eve of Israel’s creation. You can find a lot of work written about the history of ancient Israel and Judea up to the time of the Roman occupation, but from the early middle ages onwards, when Jews became a minority in Palestine, I have noticed it is not all that easy to find decent, concise accounts of these centuries in which they were, demographically, barely hanging on, up until the arrival of the first Zionist colonists at the end of the 19th century. So the focus will be on this, less well-known period for the most part. There will be an emphasis on comparisons with the fate of Jews in Europe in what follows. This is partly because comparisons can be generally instructive, but also because I want to examine the thesis that there is some particular enmity between Jews and Muslims stretching back centuries or that Islam has been particularly hostile to Judaism, compared to Christianity.

The first mention of a population identifying as ‘Israel’ is in an ancient Egyptian inscription known as the Merneptah Stele (c.1207 BCE). It is still unclear in what way this community distinguished itself from the other Canaanite peoples that had long inhabited the highland area centered around Jerusalem. It may have been primarily ethnic in nature, or religious, but there is insufficient evidence one way or another to say for sure. Nor is there any evidence that indicates the existence of an organised state until later on. Traditionally, the first state of Israel was believed to have been the so-called ‘United Monarchy’ which was postulated to have lasted from the mid-eleventh to mid-tenth centuries B.C. It should be noted, however, that there is no conclusive archaeological evidence for the existence of such a kingdom during this time, nor are there any references to it in contemporary sources outside the Bible. Even less-attested is the Biblical origin-story of the patriarch Abraham and his wife Sarah, their sons Isaac and Jacob (later called Israel) and so on, once believed to have been historical figures who lived in the second millennium. Consensus now is that these were stories—the elements of a national foundation myth—that their origins a thousand years later.

This points to a danger in relying too heavily on the Bible as a historical source. As Paula McNutt has put it, this risks ‘engaging in a kind of circular reasoning—that is, generating a cultural and historical “reality” from a text and then turning around and trying to understand the same text in relation to the background that was reconstructed from it’. (McNutt 3) So, if we’re talking about solid evidence, the first Jewish states were the southern Kingdom of Judah and a northern Kingdom of Israel, both of which were in existence by around 930 BCE. In ridiculously-broad strokes, the northern kingdom was conquered by the Assyrians in 722 BCE, while Judah suffered the same fate at the hands of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE. This event involved the exile to Babylon of a significant portion of the population, in particular of priests and ruling elite figures. The following period of Babylonian captivity was seminal for the history of the Jews and their religion. The exiled community was responsible for important sections and elements of the Bible and the experience strengthened and solidified Jewish identity-formation with respect to other peoples.

Babylon was conquered by the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great in 538 BCE and the Jews were allowed to return to Judah. The area remained under Persian rule for the following two centuries, until the conquests of Alexander the Great rolled into town, ushering in a period in which the Jews inhabited the frontier between the Seleucid Empire on the one hand and Ptolemaic Egypt on the other, both Hellenistic successor states of the empire Alexander founded. While Seleucid rulers were initially tolerant of the Jews’ religious traditions, tensions eventually emerged which led to the Maccabean Revolt of 167–160 BCE resulting in the establishment of a dynasty of indigenous rulers, the Hasmonean dynasty. This was gradually brought into the sphere of Roman influence to the point where Judea became a Roman vassal state. The Roman Senate eventually appointed a new ruler in 40 BCE, Herod the Great, who oversaw the further erosion of Judean autonomy until the point at which it became a Roman province in 6 CE. The crushing of Jewish revolt against Roman rule (66–70 CE) was an important chapter in the destruction of a coherent Jewsish polity and religious organisation in the area. Jews nevertheless probably remained in the majority until the period of Byzantine rule, beginning in the 4th century, after which Palestine was part of the Eastern Roman Empire. An increasingly-intolerant Christian community imposed harsher and harsher restrictions on Jews during this period. This, added to increased Christian immigration to the area, meant that Jews probably numbered less than 20% of the population on the eve of the Arab conquest of the 7th century.

Okay, so that’s almost two millenia of Jewish history summed up in a couple of paragraphs. The Muslim Arabs began their conquest of Byzantine Levant in 634, just two years after the death of Muhammad. The region was primarily Christian at the time, but Islam had already come into contact with Judaism during the Prophet’s lifetime. The conflicts that occured in Medina between his followers and the Jewish community are sometimes cited as setting the tone for a future history of enmity between the two religions, but this is deeply misleading. What really occured after the Hijra (Muhammad’s departure from Mecca to settle in Medina) was that he sought support from influential Jewish tribes against his enemies in Mecca. An alliance was made, but this broke down in successive stages, leading to bitterness and hostility as some of the Jews he had allied with went over to his enemies’ side. The frustration of these diplomatic ambitions were allied to the frustration of hopes that the Jews (as monotheists awaiting a prophet) would accept Muhammad as the real deal. When this failed to transpire, the tone of condemnation grows more apparent in the Qur’an and expulsion and (in at least one case) massacre was the fate awaiting those Jews who failed to help the Muslims as they gathered adherents in their fight against Mecca and pagans generally. These events need to be seen in their historic context, however, as reflecting the politics of a particular historical moment rather than reflective of some intractable hostility towards Judaism grounded in Islamic theology.

As Mark Cohen has noted, the harsh treatment of the Jewish Banu Qurayza tribe for example, far from representing a turn from initial toleration to hostility towards the Jews, actually did not represent a precedent. (Cohen in Meddeb and Stora 61) If anything, the early history of relations between the two religions speaks to a state of affairs which, if it cannot be described as ‘tolerance’ in the modern sense of the word, represented a kind of contract between the dominant religious community and non-Muslims, in which the latter’s subjugated status was regulated, but at the same time many of their rights in terms of personal safety/property and freedom of belief were guaranteed. Jews, Christians and all other people ‘of the book’ (i.e. monotheists; pagans were beyond the pale) were known as dhimmi or ‘protected people’ and the normal course of affairs throughout the middle ages and the early-modern period was for these dhimmi to be guaranteed protection from arbitrary oppression and forced conversion if they accepted the formal impositions imposed on them, such as the payment of a tax imposed on non-Muslims, the jizya, and restrictions on the building of places of worship.

This was pretty much as close as the middle ages came to ‘toleration’, and far closer to toleration than the situation of Jews in Christendom. It should also be noted for historical perspective that the idea of ‘tolerance’ as a virtuous trait is a fairly recent invention. Any self-respecting Christian or Muslim until the modern period generally viewed tolerance of other faiths as a neglect of their duty to propagate their own. Criticism of other religions was based on the premise that its tenets were false, not that its adherents were intolerant. (Lewis 3-4) Any talk of ‘toleration’ in that sense must therefore be tempered by an recognition that this is not what was being aspired to. Glaring differences are nevertheless apparent in the lot of Jews in Christian Europe and the Dar al-Islam. There was nothing in the Islamic world analogous to the specific law targeting Jews that were enacted in many European countries. (Cohen in Meddeb and Stora 65) It has been argued that conquest by Islam may have been relatively less onerous for Jews compared to Christians and Zoroastrians. While these had enjoyed a privileged status in the Byzantine empire and Sasanian Iran respectively, Jews had lived as a minority in these realms already; domination by an overbearing religious community was just more of the same for them. (Rustow in Meddeb and Stora 77)

Either way, in Islam, Jews were just another group of dhimmi, subjected to generalised discriminatory legislation as non-Muslims, but not as Jews. The converse—that in many parts of Europe, Jews were the only significant religious minority—may partly explain why Christian Europe was comparatively less tolerant. There are other factors that plausibly explain this difference (Meddeb and Stora 30-32) of course, among them the proselytising impulse in Christianity that could not fully accept Jews until they had converted to Christianity. Whereas the dhimmi system allotted a place (albeit an inferior one) to non-Muslims within Islamic society and left them to it, there was simply no place for non-Christians in a Christian society until ideas of secularism and religious freedom began to take root in the 18th century. Islam on the other hand, contained injunctions against compelling others to convert in the text of the Qur’an itself (Sura 2:256), although once again this should not be mistaken for ‘tolerance’ of other faiths, but was merely a warning against compelling an insincere or superficial conversion.

Ultimately, judging two religions in some kind of competition for who was more ‘tolerant’ is a bit silly and not an exercise in serious history. Any black and white depiction of a tolerant Islam contrasted with an intolerant Christendom would be a simplification. Both in time and place, conditions deviated from any generalisation. There were periods of persecution under the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim (996–1021) and by the Almohads in North Africa in the 1140s, in which thousands of Jews and Christians were killed and thousands subjected to forced conversion. But again it must be noted that these atrocities were inflicted upon all non-Muslims, not directed specifically at Jews. The Almohads, indeed, persecuted Muslims they regarded as insufficiently zealous. Even these dark periods cannot be interpreted, therefore, as instances of hatred towards Jews as Jews or inchoate antisemitism.

What about Palestine then? As noted above, Jews were likely already a minority in Palestine by the coming of Islam, at which time the Christianity of the eastern Byzantine empire was ascendant and the area divided up into the provinces of Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda and (later) Palaestina Tertia (see map above), these in turn being a part of the larger ‘Diocese of the East’, which stretched from modern-day Turkey, through the Levant and all the way to Egypt. The position of Judaism in early Christianity was ambiguous, and the degree of persecution which they suffered ebbed and flowed over time as political exigencies, religious fervour and the state’s ability to enforce its will waxed and waned. While not as systematic and relentless as that meted out to pagans, Jews were excluded from government service and subject to periods of forced conversion, destruction of synagogues and other forms of persecution, especially under Justinian I (527-565). On the other hand, they enjoyed certain legal guarantees during some periods at least, that were not unlike the dhimmi system in Islam. One curious feature of Christian thought was that the Jews should be kept around as a living reminder of the punishment God imposed on those who refused to acknowledge Jesus as their messiah.

That the Jews of Palestine chafed under the yoke of Byzantine power is suggested by the fact that they took advantage of the empire’s war during the reign of Heraclius (610-641) with the neighbouring Sasanian Empire (Iran) in 613 to join forces with the invaders in an attempt to carve out some kind of autonomous polity for themselves. Under Persian occupation, the Jews were reportedly given control over Jerusalem from 614 to 617, but this ended badly when the Persians changed policy and abandoned their allies. When Heraclius recaptured Palestine in 628, despite promises of a pardon, a general massacre of Jews occurred at the instigation of his priests and monks. Legend records was that Heraclius’ astrologers freaked him out with predictions that his empire would fall to a nation of circumcised people. Mistakenly believing this meant the Jews, the emperor unleashed a campaign of forced conversion to forestall the danger, not realising the prophesised danger was incubating to the south, in Arabia. (Falk 353-4)

It would not be surprising then to find that the Muslim conquest of Palestine was welcomed by the Jews. Evidence for the response of the population is thin on the ground. The Hebrew scholar David ben Abraham al-Fasi (who lived in a later period) is sometimes cited as noting that the Muslims allowed the Jews to pray on the Temple Mount, a practice that had been forbidden them under Christian rule, indicating some improvement in conditions. It seems likely in any case that Jews had been forbidden from settling permanently in Jerusalem under Christian rule, a prohibition which would eventually be lifted under Islamic rule. (Rustow in Meddeb and Stora 82) At the same time, however, the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (685–705) undertook major building projects on sites that had been sacred to the Jews, most notably the Dome of the Rock, situated on the Temple Mount. Any perceived toleration of the Jews’ presence, therefore, must incorporate the fact that the Muslims clearly saw their own faith as having superseded Judaism.

On the whole it may be that—beyond the imposition of the jizya and the fact that the Christians joined the ranks of the non-privileged—Muslim rule in the early period at least did not bring any immediate revolutionary changes for the indigenous population. Lacking traditions of highly-developed state institutions and urban development, the Arabs retained the existing Byzantine civil service and its personnel, and Greek would remain the language of administration for decades after nominal Arab conquest. A willingness to assimilate and incorporate the culture and personnel of the conquered extended to entrusting positions of high office to Jews in various Islamic states. This was particularly true in al-Andalus, the areas of Iberia conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate in the early 8th century. Often described as a Golden Age of Jewish culture, historians debate the extent to which Muslim Spain was an inter-faith utopia, but at the very least it can be said that Jews enjoyed a freedom to practice their faith and advance socially in a way that was unthinkable in the other medieval kingdoms of Europe.

This is attested to by the migration of Jews from around Europe to al-Andalus and by the prominence of Jewish individuals in trade, art and politics. Hasdai ibn Shaprut, for example, was a Jew who rose to the rank of vizier (a high-ranking advisor somewhat analogous to a prime minister) to Abd al-Rahman III, Umayyad Emir and then Caliph of Córdoba in the 10th century. Samuel ibn Naghrillah, likewise held a similar position in the kingdom of Granada in the next century, as did his son, although the latter’s success provoked such jealously and suspicion from the population that he was assassinated, followed by a general massacre of the Jews in 1066. Maimonides (1138–1204), a Sephardic rabbi and philosopher, could likewise be cited as an example of the prominence and status of Jews in this period. He was, however, expelled from Córdoba by the puritanical Almoravids for refusing to convert to Islam, symptomatic of a decline in tolerance that signalled the end of the Golden Age.

This period also witnessed a deterioration in the position of Jews in Christendom. Even under Justinian, whose legal code saw an intensification of repression, Judaism had at least been recognised as a religion, albeit an inferior one, and its subordination regulated in a manner not dissimilar in principle to Islam. As the middle ages progressed, however, the reality as opposed to the legal theory became harsher for Jews (and Muslims) as religious minorities in Europe. This is partly a result of the ideological impulse to convert non-Christians, but also a result of political tensions resulting from the conflicts between Christendom and Islam in the Reconquista and the Crusades. This also resulted in a worsening of the position of the dhimmi under Muslim rule, but, as Bernard Lewis has pointed out, as a general rule ‘Islamic practice on the whole turned out to be gentler than Islamic precept—the reverse of the situation in Christendom’. (Lewis 24)

Lewis incidentally, who I have criticised previously on this blog, could never be accused on painting Islam in a rosy or uncritical light; quite the contrary, he was described on his death a few years ago as ‘a notorious Islamophobe who spent a long life studying Islam in order to demonise Muslims’, someone who had spent ‘a lifetime studying people he loathes’. (Dabashi 2018) So, not someone inclined to soft pedal its record towards minorities in any period. The scathing critique cited above is essentially correct; Lewis was a bit of a bigot, and he seemed to get worse as he aged, and yet I found his 1984 book The Jews of Islam to be fairly well-balanced and faithful to its sources.

Discussion of the Crusades provides a good opportunity to return the focus to Palestine. Jerusalem was, after all, the ultimate goal and focal point of Christian military campaigns set in train by Pope Urban II in 1095 against a background of reformist zealotry in the west and a request for military aid from Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, who was facing a serious military threat from the Seljuk Turks in the east. There were other, less altruistic, motives driving Western Christendom to launch this massive movement of men and arms against the eastern Mediterranean, the first of many such attacks staged every few decades throughout the 12th and 13th centuries. This is not the place for an in-depth narrative of the Crusades, however. The salient point for us is that the Crusaders succeeded in their aim of capturing Jerusalem in 1099. The city and surrounding country had been disputed for decades between two rival Muslim powers, the Fatimids—a Shia dynasty of North African origin who had made Cairo their capital—and the aforementioned Sunni Seljuk Turks. While the latter had captured the city in 1071, the Fatimids took it back on the eve of the Crusades. The crusaders conquest of the city inaugurated a period of almost a century of Christian rule under a ‘King of Jerusalem’, until re-taken by the Seljuks under Saladin in 1187. The Kingdom of Jerusalem as a polity lasted until 1291, although its capital moved north to Acre.

It did not bode well for the Jews of Palestine that the Crusaders had, en route to the ‘Holy Land’, massacred Jews they encountered in Germany in 1096. By this time, the centre of Jewish population in the region had moved to Tyre (Frenkel in Meddeb and Stora 156), but the number of Jews in Jerusalem was still significant enough to be mentioned in accounts of its defence against the Crusaders. Jews fought alongside Muslims and, in defeat, suffered similar atrocities at the hands of the invaders. Concrete figures are difficult to come by, but the Crusaders appear to have gone on an indiscriminate killing spree against all non-Christians, man, woman and child. The eyewitness Raymond of Aguilers wrote of soldiers riding in blood up to their knees and bridle reins. Many Jews fled into their synagogue, whereupon it was burned to the ground by the Christians. Approximately 40,000 souls were murdered in the taking of Jerusalem. (Kostick)

Once things had settled down, a kind of dhimmi system was imposed by the Crusaders on the conquered population. The reality of this dispensation perhaps bears out Lewis’ observation above that Christian practice tended to be harsher than precept. The rape of women, enslavement, arbitrary violence at the hands of Christian rulers and the landed gentry they imported continued to be a reality of life for some time after the conquest. The old Byzantine prohibition against Jews living in Jerusalem was re-introduced. Orthodox Christians native to the area were classed alongside Jews and Muslims as a second-class untermensch. By the time the Jewish-Iberian traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited Jerusalem in 1173, there were only 200 Jews (possibly only 4, depending on how you reading the Hebrew characters in his account) living in Jerusalem, mainly associated with the business of dyeing cloth. Little more than a decade later, the city was reconquered by Saladin’s forces and the Sultan issued a proclamation inviting all Jews to return and settle in Jerusalem.

The return of Muslim control over Palestine brought a recovery of sorts in the Jewish population. It is difficult to quantify this recovery; some sources claim it began more or less immediately after the Muslims retook control, others that it did not really occur until the 1260s, when Moses ben Nachman, a rabbi and scholar who had been forced to leave Spain in his old age by the persecution of the Dominicans, settled in the country. Nachmanides as he is more-commonly known, is a figure often closely associated with this refounding of the Jewish community in Jerusalem, where he founded a synagogue in 1267 and settled in Acre, dying there three years later. This theme—of the Jews seeking refuge from Christian persecution in the Muslim lands—is one that looms large in the centuries ahead, especially as the Spanish Christian conquest of al-Andalus known as the Reconquista intensified. This final push to expel all Muslim taifas from the Iberian peninsula was in reality a long drawn-out process that took centuries, culminating in the fall of the Granada emirate in 1492. Of relevance for our story is the fact that this process was accompanied by an intensification of religious intolerance, directed not only against Muslims but the Jews. A particular low point was the year 1391, in which untold thousands of Jews were murdered across Castile and Aragon. It is estimated that about half of the survivors converted to Catholicism to avoid a similar fate.

The Golden Age was a distant memory by this stage. The persecution reached its peak in the same year Granada fell, as the ‘Catholic Monarchs’ Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon issued the Alhambra Decree ordering the expulsion from their kingdoms of all practising Jews. In its wake, over 200,000 Jews converted to Catholicism to avoid leaving and between 40,000 and 100,000 were expelled. Over the following centuries a sustained migration took place of Jews from not only Spain, but all over Europe. Some went to the nearby Maghreb (where a significant Jewish population would remain until the 20th century), others went to those parts of the eastern Mediterranean under Ottoman control. Some, of course, went to Palestine, which at the time of the expulsion was under the control of the Egypt-based Mamluk dynasty. By 1517, however, it has been conquered by the expanding Ottomans who had conquered Constantinople in 1453. This confluence of events—Spanish expulsion of Jews and Ottoman rule—would provide the backdrop for the following four centuries of Jewish life in Palestine.

In the Ottoman lands generally Jews were—and the word is used by numerous historians—welcomed by the regime. This welcome may well have been motivated by pragmatism as much as tolerance and goodwill, but nevertheless it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the leading Muslim power in the early-modern world was, in effect, a refuge for Jews against Christian persecution. We do not need to portray the Ottoman Empire as some kind of liberal utopia concerned with human rights to explain this. The Sultan in Constantinople saw the Jews as an educated, enterprising group who brought skills and in some cases capital with them to his domains. This utilitarian view of Jewish immigration is supported by the way the Ottoman regime occasionally took it upon themselves to resettle Jews from one part of the empire in another as a kind of social engineering. (Veinstein in Meddeb and Stora 179)

It nevertheless remains the case that, just as in medieval al-Andalus, it was possible for Jews to advance high up the social and professional ladder in the Ottoman empire. Perhaps the most famous example of this was the Nasi family, particularly Joseph Nasi and his aunt/mother-in-law Gracia Mendes Nasi, who had fled Spain first to Portugal and finally ended up in the Ottoman domains in the 1550s. Joseph became a wealthy trader and powerful diplomat under the Sultan Selim II, being given the title Duke of Naxos. Salomon Aben Yaesh (born Alvaro Mendes in Portugal) was another hugely wealthy and influential Jewish trader who moved to Thessaloniki (one of the most popular destinations for Jewish immigrants in the Ottoman Empire) to practice his religion freely. He used his contacts all over Europe to gather important intelligence for Sultan Murad III and was made Duke of Lesbos.

It may be useful at this point to define a few distinctions that will become important going forward. Those that left Spain (ספרד or Sefarad in Hebrew) came to be known as Sephardic Jews. They brought with them their own skills and culture to their new home, where they preserved their form of Castilian Spanish which would become known as Ladino or Judeo-Spanish, which is still spoken today by a minority (mostly older people) in Israel. In Palestine, they tended to integrate and intermarry with the pre-existing Arabic-speaking Jewish population and with other Jewish immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa, often referred to as Mizrahi (of the Orient) Jews. These groups tend to be defined in contrast to Ashkenazi Jews, those of central and eastern European origin, the word ‘Ashkenaz’ referring in medieval Jewish tradition to the region along the Rhine River. The origins of this community are debated but, in broad strokes, emerged from migration into Germany from the same dispersion out of Iberia and other Medditerranean lands, later re-settling all over eastern Europe. By the late 18th century Russia and Poland were home to about half of the world’s Jews. (Dowty 44)

Like the Sephardic Jews, the Ashkenazi developed their own language, Yiddish, a variant of High German with Hebrew influences. The treatment of the Ashkenazi in many European lands was far harsher than that of Jews in Muslim countries, however, and they were subject to frequent state-sponsored persecution. Most Jews in the Russian empire lived in areas like Poland and Ukraine that had been annexed, and were forbidden to live outside this ‘Pale of Settlement’. Within this area, they were mostly kept in grinding poverty and subjected to intermittent pogroms. The word ‘pogrom’ itself is a loan-word from Russian and found its way west after a wave of antisemitic riots swept through this area in 1881-84 after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. This violence is also said to have convinced many Russian Jews that any hope of assimilation into Russian society was futile and that emigration was the only option. Most fled to the United States, but a few chose the relatively-novel idea of emigration to Ottoman Palestine.

This idea of Jewish settlement into the area where the Jewish states of antiquity happend to have been situated was one that had never completely died out, and sporadic attempts had been made to lead groups of Jews from Europe and other parts of the Ottoman empire to settle in Palestine (by among others the aforementioned Nasi family). It was only in the late 19th century, however, that an ideology of constituting a Jewish homeland in the area and practical plans to bring this about, were developed. A group known as Hibat-Tsion (Lovers of Zion) was founded in 1884 by a Russian doctor, Leon Pinsker, who had been disabused of the idea of assimilation into Russian society by the aforementioned pogroms. This pre-dated the more-famous Zionist Organization of Theodor Herzl by more than a decade. This wave of Jewish immigration in the 1880s-90s, known as the First Aliyah, was mostly economically motivated and individualistic in its objectives. It is often distinguished from the Second Aliyah (1904-1914) which was more ideologically cohesive and conscious of their settlement being the precursor to the establishment of a Jewish state at some point in the future.

The idea must have seemed far-fetched at the time. By the time the Ottomans conquered Palestine in 1517 it was a backwater. If a motorway had existed between Egypt and Syria in those days, it was the kind of place they’d have built a bypass around. Urban populations had declined, the population was mostly rural and poor, the area’s only fame attached to its sites of religious interest. The centre of Jewish life in Palestine was actually Safed in Galilee, only later being superseded by Jerusalem at some point in the 17th century. Few were induced to settle in the region. A notion of Palestine as the ‘Holy Land’ developed during the Ottoman period, not necessarily as a place to live but as a place to be cherished in the imagination, a place in which the small Jewish population clinging on prayed for their co-religionists out in the diaspora and were in return supported by charity from the latter. As Yaron Ben Naeh has put it, Palestine had become, by the early 19th century ‘a faraway ideal rather than a tangible reality […] more than an inhabitable space, it was rather the land of holy places in which elderly believers came to live out their last days.’ (Ben Naeh in Meddeb and Stora 208)

Many visitors to the region in the 19th century—not least the first Zionist settlers—were struck by the wretched poverty of the indigenous Jewish community. Given the examples of Jewish success in the early-modern period cited above, this begs the question: what happened? This decline reflects a broader decline in the Ottoman empire as a whole. Lewis argued that an important factor in Jewish success originally had been their European contacts and knowledge, language skills etc. that had made them useful to the Ottomans. As time passed and contact with their countries of origin faded, these were lost and, moreover, such skills were acquired by other minorities such as the Greeks and Armenians. The rising power of European nation states was another factor. Christians in the Ottoman empire enjoyed their support, while Jews did not. (Lewis 141-143) In Palestine specifically, another reason that has been suggested is that, as time when by, Jewish immigration changed in complexion. An influx of older Jews arriving to spend their last years in the Holy Land has already been mentioned. Also of importance was the demographic shift within the Jewish community towards Ashkenazi Jews.

The first known Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem dates from 1687, shortly followed by a significant influx of settlers from Poland led by a preacher known as Judah the Pious, who brought a group of over 500 people to settle in Palestine in 1700. Unlike the pre-existing Jewish population that had integrated comfortably into Ottoman society, however, European Jews tended to resist acculturation, choosing to remain European in culture or even adopt Ottoman citizenship. Unlike Sephardic Jews, they kept the Arab population at arms length and resisted integration to the local economy. Tensions followed, not only with the local Arab population and Turkish authorities, but also with their Sephardic co-religionists. In 1720 a mob stormed the Ashkenazi quarter in Jerusalem and shortly afterwards European Jews were forbidden from entering Jerusalem, a ban which would only be lifted in the early 19th century. (Dowty 29) It was from around that time that the Ashkenazi proportion of the population in Palestine began to swell.

Ashkenazi failure to integrate in the economy has already been mentioned. Unfamiliar with the local language and customs, lacking the skills needed to thrive in it, the fate of many European Jews in Palestine at this time was to be supported by charity from the diaspora. (Ben Naeh in Meddeb and Stora 207) It might be imagined that the series of reforms instituted by the Ottomans in the mid-19th century would alleviate these problems. These measures known as the Tanzimat were a series of constitutional reforms intended to modernise the Ottoman state and, among other things, inculcate a sense of Ottoman national identity in order to stem the tide of nationalism among its non-Turkish subjects. In theory, they gave Jews and other non-Muslims the same rights as Muslims, making them citizens equal under the law. This meant the end of the jizya, but at the same time introduced obligations to the state that they hadn’t had before, a duty to serve in the army for example. The Ottomans meanwhile recognised the status of non-Muslim religious groups as millets (communities of the empire), giving groups like the Jews a significant degree of autonomy to administer tax collection, education, legal and religious affairs of their own communities.

Other developments of the period, however, undermined any good these enlightened reforms might have made. The Tanzimat was partly an attempt to halt the decline of the Ottoman state, which had fallen behind the nation states of Europe by the mid-19th century when it earned the epithet ‘the sick man of Europe’. This is not the place for a detailed explanation of how this came about (economic and technological stagnation, military defeat, nationalism in the regions) but one of the consequences was the ‘capitulations’, contracts the Ottomans made with the big European powers which gave citizens of the latter extensive rights and privileges in Ottoman territory.

These agreements had originally been made when the Ottomans were powerful, and were designed to entice European trade and investment, somewhat like Special economic zones in China. By the 19th century, however, the balance of power had changed dramatically and the capitulations had become an instrument for European powers to exert influence in Ottoman territory and undermine the latter’s sovereignty. European citizens were, by the capitulations, often exempt from local prosecution, taxation, conscription and many other obligations borne by other residents. The upshot of all this for the Jewish community was that many Ashkenazi Jews chose to avail of these rights as European citizens, settling in Palestine but benefiting from the protection of their countries of origin. This accentuated the sense of separation between them and everyone else around them, including other Jews. This went so far that in 1867 Ashkenazi Jews in Jerusalem asked the Ottoman government to recognize them as a separate sect from the Sephardic community, allowing them complete autonomy from the latter’s institutions. (Campos 18)

The capitulations generally, and European championing of certain groups’ rights, can be seen as a method by which western powers got their tentacles into Palestine, just as Egypt, the Balkans, North Africa were also subject to European encroachment at this time. Palestine was being prising away from Ottoman control…and into someone else’s control, in a process which, as Ilan Pappé has noted, has often been presented by historians as synonymous with ‘modernisation’. (Pappé 2006, 2) That this was done under the guise of protecting religious minorities is rather ironic and frankly cynical, when you consider the antisemitism of Europe itself. Even Tsarist Russia—probably the worst place to be a Jew—got in on the act as a means of augmenting their influence in the region. They were late to the game, however. In 1848, the regime had told Russian Jews seeking its protection to look elsewhere. The British consul was happy to oblige, having few British Jewish immigrants in the area to take advantage of—ahem—protect. It was not until 1890 that the Russians realised the strategic utility of defending Russian Jews in Palestine (the largest group of foreign Jewish citizens resident there)…while persecuting them mercilessly at home, and reclaimed its jurisdiction over Russian Jews on Ottoman territory. (Dowty 33)

While in some ways, European society was becoming more liberal and tolerant in the early to mid 19th century, in others it was becoming more antisemitic. This period saw the legal emancipation of Jews in many European states, but at the same time a ‘new antisemitism’ was emerging in reaction to these liberalising developments, a hatred ‘based less on religious and more on racial grounds’. (Dowty 53) This new strain of hostility against Jews built upon earlier prejudices but, unlike earlier anti-Jewish sentiment, was unwilling to accept even those Jews who had converted to Christianity. It posited an indelible stain of racial Jewishness that could never be assimilated, in keeping with pseudoscientific theories of the time, and argued that the most assimilated Jews were in fact the most dangerous as a potential fifth column, feigning loyalty to the nation but really serving other masters.

These new antisemites in fact were the ones who came up with the term ‘antisemitism’, believing it gave off an aura of scientific respectability, and organised the First International Anti-Semitic Congress in 1882 in Dresden. Other events such as the Dreyfus affair (1894-1906), the success of the antisemite Karl Lueger as Mayor of Vienna from 1897-1910 and of course the rise of the Nazis, fascism and the Holocaust, are testament to the worst that was was still to come for European Jews. This new antisemitism was therefore a strong push factor in the emerging movement for a ‘return’ to the land of Israel which would coalesce in the Zionist movement at the end of the century. It was an idea welcomed both by those Jews who perceived they would never be accepted as equals by Europe’s antisemites, and by the same antisemites, who wished to be rid of the Jews. Another push factor was the efforts of evangelical Christians who believed the ‘return’ of the Jews to Israel and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem were prerequisites for the second coming of Jesus Christ. These Christian Zionists were increasingly putting their (frankly bonkers) ideas into practice, raising money to purchase land and fund settlers to establish Jewish communities. One of the most prominent of these was a Tory politician, the 7th earl of Shaftesbury, whose interest in the Jewish people is expressed succinctly in the following extract from an article he wrote in 1839, combining as it does his casual antisemitism with the desire to pack the Jews off to Palestine in a couple of sentences:

…the Jews must be encouraged to return in yet greater numbers and become once more the husbandman of Judea and Galilee … though admittedly a stiff-necked, dark hearted people, and sunk in moral degradation, obduracy, and ignorance of the Gospel, [they are] not only worthy of salvation but also vital to Christianity’s hope of salvation.

Given that part of the plan was for these Jews to convert to Christianity and usher in the end times, it seems unlikely that concern or love for Jews motivated people like Shaftesbury, nor does it motivate the many Christian fundamentalists in America today who support Israel so staunchly for the same reason.

The problem with all these plans was, of course, that Palestine wasn’t empty. It almost escaped my mind to mention the narrative, promoted by the Israeli state and education system and some Americans, that Palestine was a barren desert before Zionism. This fantasy is frankly beneath contempt and I won’t even discuss it here, but for a thorough debunking of it, based on excellent Israeli scholarship, see Ilan Pappé’s, Ten Myths About Israel which when I checked last was being given away for free as an ebook by Verso Books.

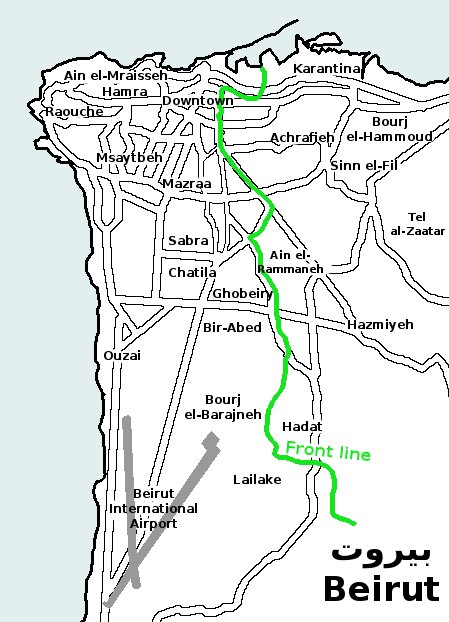

As can be seen below, Jews were still a small minority in 1900 even after the initial wave of immigration after the Russian pogroms.

| Estimated population of Palestine by religious group, based on work by Sergio Della Pergola | |||

| Jews | Christians | Muslims | |

| 1800 | 7,000 (2%) | 22,000 (8%) | 246,000 (89%) |

| 1890 | 43,000 (8%) | 57,000 (10%) | 432,000 (81%) |

| 1914 | 94,000 (13%) | 70,000 (10%) | 525,000 (76%) |

The main purpose of this post, however, has been to look at the Jewish community in Palestine before the Zionists came, the so-called ‘Old Yishuv’, and to examine the notion of an age-old hostility between Jews and Muslims. It will also hopefully have become abundantly clear by this stage that this is a myth. Even with the influx of an Ashkenazi community less amenable to integration, by the early 20th century the picture that emerges from first-hand accounts of the time is one of Jews and Muslims sharing each others daily life, living and working together, learning each others languages and customs. What tensions there were, were largely between Jews and Christians, who tended to avoid shared living spaces and occasionally came to blows around religious holidays such as Easter/Passover. Another fact worth mentioning is that while Sephardic Jews lived cheek by jowl with Muslims, they and their Ashkenazi co-religionists spoke different languages, went to different synagogues and schools and lived in different neighborhoods. (Campos 18 and Al-Jubeh in Meddeb and Stora 214)

It would be misleading, however, to portray this time and place as some interfaith utopia. Conflict between Muslims and Jews undoubtedly occurred, but sentiments that can legitimately be called antisemitic did not appear until the late 19th century, and when they did they were transmitted to the Arab world from their European source, at first through mostly French texts, while British diplomats did their part by spreading antisemitic conspiracy theories about Jewish masonic schemes and involvement in the Young Turks movement. These sentiments were no doubt fueled by fears of increased Jewish settlement and talk of founding their own state, and antisemitism provided a readymade fund of tropes to draw on. Crucial to remember, however, is that the looming conflict between Palestinian Arabs and Jews that would intensify in the following decades was political in nature, not a matter of hatred but a specific material conflict between two groups of people both claiming the same piece of land. (Lewis 173, 184-5, 189)

The possibility that the vast majority of the population might object to being pushed off their land never seemed to occur to many early Zionist settlers. Not that no-one was aware. The young Russian Jewish socialist, Ilia Rubanovich, wrote critically of Zionism in 1886:

What is to be done with the Arabs? Would the Jews expect to be strangers among the Arabs or would they want to make the Arabs strangers among themselves? . . . The Arabs have exactly the same historical right and it will be unfortunate for you if . . . you make the peaceful Arabs defend their right. They will answer tears with blood and bury your diplomatic documents in the ashes of your own homes. (translated in Dowty 83)

But the New Yishuv was different from the old, different in its sense of purpose, its determination to adopt agriculture and ‘redeem the land’, as well as its unwillingness to fraternise with not only the other religious groups already inhabiting Palestine, but even with the existing Jewish population. The Zionist movement gave the impression of being uninterested in or even downright hostile to the Old Yishuv. Its representative in Istanbul, Victor Jacobsohn, did not think they would be ‘useful’ to the cause. Other Zionist officials expressed the opinion that Palestine’s Jewish community should stay out of internal Zionist affairs, as Michelle Campos has put it: ‘in effect disenfranchising them from the very movement which sought to speak and act in their name.’ (Campos 206-7)

The project of Israel was not for these Jews. It was a European project, run by and for European Jews. Inded it is worth pausing for a moment to examine the whole idea that those Zionists settling in Palestine from the late 19th century on were ‘returning’ in any meaningful sense. It has been claimed by some that these were not descended from those Jews exiled from their homeland in antiquity; it has furthermore sometimes been claimed that the real descendants of these original Jews never left but converted to Christianity, then Islam, and are the Palestinians themselves. It must be stressed here that this argument is referring solely to genetic descent, not to people’s sense of belonging to one or other identity in a cultural sense, which to me seems to only real sense in which identity actually exists. Personally, I am not sure how this argument could even be settled one way or the other. It seems to me as plausible to say that the Palestinian Arab population are the descendants of the Jews of antiquity, as saying that the Poles, Americans, Australians etc. settling in Palestine are their descendants. Given the amount of intermixing, etc. it is questionable how meaningful the question is especially when talking about dispersed diasporic populations. Those interested in this debate can look at the work of Shlomo Sand and those who have both tried to debunk and corroborate it. On the whole, I think it the idea is a red herring and neither particularly relevant as a critique of Israeli settler colonialism, nor credible to back up the pretence you are ‘returning’ to a land somd distant answer may possibly have inhabited.

The impression that Israel was a project not for Jews, but for European (and by extension Euroamerican) Jews is strengthened by subsequent developments after the establishment of Israel, which would be dominated by Ashkenazi Jews. Their disdain for the pre-existing Sephardic and Maghrebi Jewish communities was carried over post-1948 into a contempt for those Mizrahi Jews who had come from Morocco, Yemen, Iraq and other places—often Arabic in language and culture—and their establishment as a second-class citizenry in the new state. In this light, those who characterise Israel as a European colony in the Middle East seem to have a point. The efforts of outside powers to bolster Israel also take on a different complexion to their professed concern for the Jewish people when examined more closely. Allusion has already been made above to the cynical use Tsarist Russia and Christian Zionists in Britain made during the 19th century of protecting Jews in Palestine as a pretext to attain foreign policy goals. It is hard to avoid seeing echoes of this in the United States’ obdurate support for Israel over the last 70 years.

Evidence certainly suggests that concern for the welfare of the Jewish people was not a primary factor motivating the Americans. At least until 1944, the U.S. government imposed restrictive immigration policies that severely limited the number of Jews from central and eastern Europe who could obtain refuge there. Even when the Nazis’ mass murder was underway, officials within the Department of State worked to prevent assistance to Jewish refugees and obscure information about the Holocaust. Nor was the United States massively committed to Israel until it was already a fait accompli. As late as March 1948, the administration was getting cold feet about support for a Jewish homeland, advocating at the UN for an international trusteeship over Palestine in its stead. (Pappé 2006, 120) Only when they realised the usefulness of a staunch ally in the oil-rich Middle East—and one that was almost-entirely dependent on them for military aid—did the Americans fully commit themselves to backing Israel, what US Secretary of State General Alexander Haig described in 1981 as ‘the largest American aircraft carrier in the world that cannot be sunk’. The idea was echoed by a Senator for Delaware in 1986, Joe Biden: ‘Were there not an Israel, the United States of America would have to invent an Israel to protect her interest in the region’. We see likewise a growing advocacy among Europe’s far-right for Israel, an admiration that stems more from its current prioritising of hatred towards Muslims over its traditional hatred of Jews, but one that has nonetheless attempted to present itself as being motivated by concern about rising antisemitism.

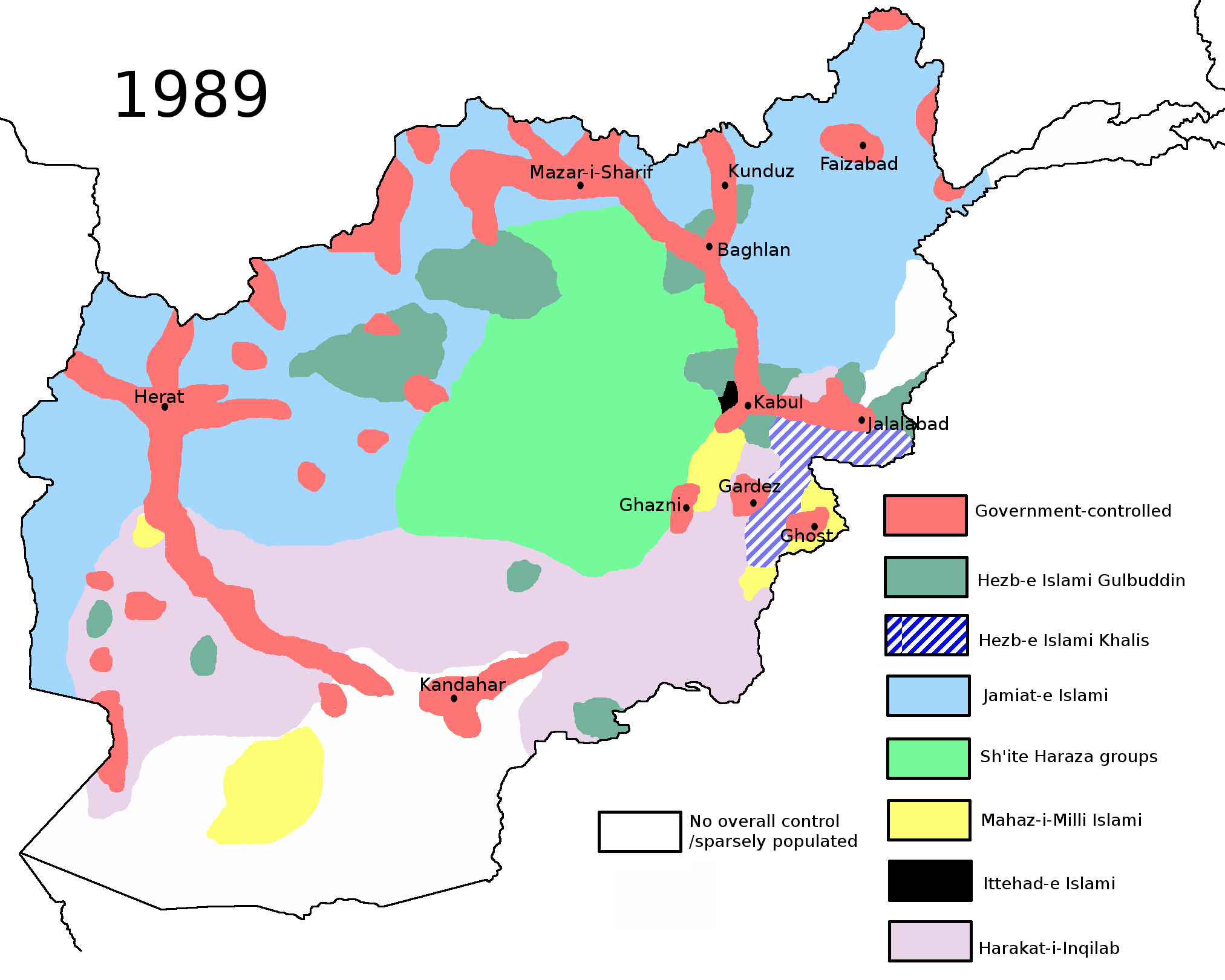

So that’s where we are now, in March 2024, with Nazis professing concern about rising antisemitism and those concerned about genocide being roundly condemned as antisemites. The world has, in other words, gone mad. But this blog was meant to be a contemporary history of the Muslim world, and I now realise I’ve spent 8000 words writing about non-Muslims and covering a space of 2000 years ending around 1900. Not particularly contemporary or maybe—like all history—it is, if you think about it in a certain way. Anyway, as recompense the plan is to get real contemporary in the next post and pick up the story where we left off in part 11, in Afghanistan in 1996, when a shadowy band of Pashtun Islamic fundamentalists seized power. If possible, I would like to try and take on the challenge of encapsulating the next two and half decades of Afghanistan’s history in one post, taking in 9-11, the U.S. invasion and western-backed government under Karzai and Ghani, up to 2021…when a shadowy band of Pashtun Islamic fundamentalists seized power.

Bibliography

Michelle Campos, Ottoman Brothers : Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (Stanford University Press, 2020)

Hamid Dabashi, ‘Alas, poor Bernard Lewis, a fellow of infinite jest: On Bernard Lewis and ‘his extraordinary capacity for getting everything wrong’. (Al Jazeera, 28 May 2018)

Alan Dowty, Arabs and Jews in Ottoman Palestine (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2021)

Avner Falk, A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews (Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1996)

Conor Kostick, The Siege of Jerusalem: Crusade and Conquest in 1099 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011)

Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam (Princeton University Press, 1984)

Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora (eds.), A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations : From the Origins to the Present Day (Princeton University Press, 2013)

Paula McNutt, Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel (SPCK Westminster John Knox Press, London, 2000)

Ilan Pappé, A history of modern Palestine: one land, two peoples (Cambridge University Press (2006)

Ilan Pappé, Ten Myths About Israel (Verso Books, 2017)

Sergio Della Pergola, Demography in Israel/Palestine: Trends, Prospects, Policy Implications (Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2001)

Featured image above: A detail from ‘Shiviti’ by Moshe Ganbash (1838/39), a map depicting holy sites of importance to the Jews in Palestine. A clickable version is available on Wikimedia commons.