‘I saw dead women in their houses with their skirts up to their waists and their legs spread apart; dozens of young men shot after being lined up against an alley wall; children with their throats slit, a pregnant woman with her stomach chopped open, her eyes still wide open, her blackened face silently screaming in horror; countless babies and toddlers who had been stabbed or ripped apart and who had been thrown into garbage piles.’

While the Phalangist militiamen were the ones who went into the camps and slit the women and children’s throats, the question of broader responsibility for the massacre would assume even greater political significance. In terms of negligence, certainly the MNF which pulled out early bears some share of blame; Arafat had begged them to return, citing the danger in which Palestinian civilians were under after the murder of Gemayel. Israel, which was in control of the area in which the camps lay at that time, obviously bears responsibility for failing to prevent the massacres. Even their own investigation held Ariel Sharon personally responsible for failing to intervene to stop the Phalangists and forced him to resign as defense minister the following year. Many observers, however, have argued that Israeli responsibility went beyond negligence and failing to prevent the massacre, to claim that they deliberately facilitated it. Certainly there is no doubt that the Israelis sealed off the camps and sent the militias in, as well as helpfully illuminating the area with flares for the next two nights while they did the killing. It has always been argued that the Phalangist militia was sent in to root out ‘terrorists’, although by this stage it seems to have been widely believed by both the Phalangists and Israelis that all Palestinians-man, woman and child-could be categorised as ‘terrorists’. Certainly they had made little distinction between combatants and civilians in their bombings of the previous months.

The massacre resulted in a rare flurry of international activity on Lebanon’s behalf, even if it was ultimately to little avail. Unusually, even the Americans were critical of the role Israel had played, with Reagan’s representative to Lebanon telling Sharon he ‘should be ashamed of himself’. Belatedly realising the catastrophic consequences of their hasty withdrawal, the MNF returned on the 20 September. The following day, Bashir Gemayel’s brother Amine was elected President with American backing. Beyond protecting civilians, the mission of the MNF was now to assist the Lebanese state to restore sovereignty and authority over its territory. Amine Gemayel enjoyed a reputation as a more moderate and consensual politician compared to his late brother, a builder of bridges between the different sects. He declared himself to be taking power in the name of all the people, and the Lebanese army were once again deployed to the streets of Beirut to restore law and order. It soon became apparent, however, that Gemayel’s power was being wielded in the interests of his own community under the guise of reconstructing the state. The Muslims in west Beirut were subject to constant harassment and arrests by Gemayel’s army, who worked hand in glove with the LF, who behaved as conquerors. People were arbitrarily detained and in some cases disappeared, never to return.

While the MNF expressed concern about this turn of events, their role as supporting Gemayel’s regime essentially turned them into collaborators with it. They were blissfully unaware, or unwilling, to see that they had become partisans in the war rather than a neutral force. This disjoint between self-image and reality is evident in the following short video about the U.S. Marines’ presence in Lebanon in 1982. You can either turn the sound off or listen to the audio with propaganda sensors on full power. The narrator typifies the attitude of many Americans, oblivious to (and not very interested in) what the war was about, and the delusion that they stood aloof, keeping the warring parties apart. The litmus test for such a claim is, did the Marines confront the IDF or their Christian allies? Not likely.

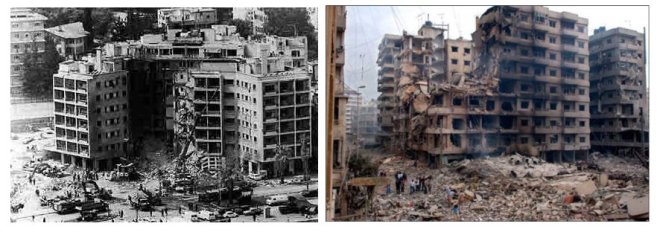

The barracks bombing was the biggest single attack on the U.S. military since Iwo Jima, and the biggest loss of life of Americans in one attack until 11 September 2001. These attacks were some of the first instances of suicide bombings in the modern era. Attacking the enemy without being hampered by any regard for your own survival is, of course, nothing new. The Japanese kamikaze pilots most famously adopted it in the Second World War. Until its emergence in Lebanon in the 1980s, however, it was rare for non-state actors in conflict to employ it. It would become all-too common in the decades that followed up to the present day. The standard explanation is that this dramatic rise in suicide attacks was due to a new religious fanaticism colouring conflicts in the middle east. Of course, this cultural dimension to the act cannot be entirely dismissed. The emphasis on death over dishonour in traditional samurai culture no doubt played into the willingness of Japanese soldiers to take their own lives, just as the cult of martyrdom in Shi’ism influenced the ‘human wave’ attacks of Iranian soldiers after the revolution. More than a readiness to commit suicide in killing the enemy, I think it is the celebration of this sacrifice that really characterises these cultures. When you think about it, there have been many circumstances where soldiers from European armies were sent into certain death (the columns of soldiers in World War One marching across no-man’s land towards machine-gun fire armed only with batons springs to mind), but these were not explicitly celebrated as suicide attacks, even though they basically were. Beyond the cultural dimension, I think it is worth considering something the author J.M. Coetzee has observed of suicide bombers, that they may be ‘a response, of a somehow despairing nature, against American and Israeli achievements in guiding technology far beyond the capacities of their opponents’. That is, they are a function of the asymmetry of wars which have become so unequal that the weaker party have few means of retaliation left open except to take their own life.

But I digress.

The result of this bombings was that the MNF withdrew in the Spring of 1984. The Americans essentially washed their hands of Lebanon and despaired of re-establishing state control over the country. This American withdrawal might seem surprising to us who have lived, post-2001, with a United States that has not been shy to retaliate with overwhelming and disproportionate power to attacks on its citizens, even against people who were not responsible for those attacks. In the 1980s, however, it was less than a decade since the humiliating retreat from Vietnam, and American public opinion was less than enthusiastic about foreign adventures, especially in wars they didn’t understand, or want to understand. The United States regime knew this, and contented itself with either fighting through proxy armies like the Contras in Nicaragua, or wars in which they would meet no significant opposition, such as the tiny island nation of Grenada, which was invaded just two days after the barracks in Beirut were bombed.

Who were these new actors in the Lebanese civil war, who had declared war on the American superpower in their backyard and succeeded in frightening them away? The bombings were claimed by the ‘Islamic Jihad Organization’, a shadowy guerrilla movement which was so shadowy that its existence was only attested by the telephone calls made to claim responsibility for bombings. Many observers, indeed, denied that the organisation even existed in any real sense, and that it was merely a front used by the Islamist militia in order to avoid directly associating themselves with certain acts. This movement, growing in strength at this time, funded by Iran and trained by its Revolutionary Guards, was Hezbollah.

We have already encountered a Hezbollah (The Party of God) in revolutionary Iran, and this Lebanese version, though it would be oversimplistic to describe it as a foreign branch of the Iranian, was profoundly influenced and guided by the latter. It had been active since the Israeli invasion of 1982, when Iran sent 1500 Revolutionary Guards to Lebanon with Syria’s consent. It was only gradually, however, that the outside world was beginning to realise there was a new Islamist grouping in the conflict. We have already examined the situation of the Shia in the last post, as well as the Amal movement, which had emerged to defend their interests and fought the Palestinians in the south, who were blamed for bringing the wrath of Israel upon the area. Amal, although founded by a Shi’ite cleric and characterised as a Shi’ite group, had secular features in that it reached out to all sectors of the community and did not aim at the establishment of an Islamic state (for which reason it had poor relations with the Iranian revolutionaries). Hezbollah was different in that its aims were explicitly non-secular, aspiring towards a theocracy such as that established by Khomeini in Iran. Its immediate aims were the expulsion of foreign armies (except the Syrians, who supported it) from Lebanese territory and the reform of the Lebanese political system to reflect more fairly demographic realities.

With the occupation of the south by Israel, the population of poor urban Shia in Beirut was increased by refugees from that area. Some of these lived in the Palestinian refugee camps and formed a significant proportion of the victims of the Sabra and Shatila massacres, not to mention the repression carried out by Amine Gemayel. There was therefore no shortage of grievances to push people into supporting either Amal or Hezbollah. Notwithstanding their common enemy, conflict between the two factions was probably inevitable given they vied for the same constituency. Indeed, this last decade of the civil war will be marked by as much by intra-sectarian fighting as inter. Amal, after the disappearance of Musa al-Sadr in 1978, was led by his colleague Hussein el-Husseini, who resisted committing the movement to military engagement in the civil war beyond fighting the Palestinians in the south (see last post), whom they also regarded as interlopers. This more moderate leadership was ousted in 1980, however, by Nabih Berri (below), who represented the more militant grassroots of the movement.

Tensions began to emerge within Amal about the role Islam was to play in the movement, and a breakaway faction known as Islamic Amal, was formed in 1982, which would eventually be absorbed into Hezbollah. Amal’s involvement in the war gradually extended to fighting not only the Israelis, but the Gemayel government as well. At the same time, they would find themselves embroiled in a conflict with Hezbollah for the allegiance of the Shia community. These two conflicts, which dominate the middle of the 1980s, are known respectively as the ‘Mountain War’ and the ‘War of the Camps’, and involved numerous other actors besides the two Shi’ite factions. To explain them illustrates well how smaller conflicts in Lebanon became entangled within larger ones, and necessitates broadening the canvas once again to the national stage.

In the Mountain War, the mountains in question were those of the Chouf region, dominated by the Druze and their leader, Walid Jumblatt, who narrowly avoided being killed by a car-bomb in December 1982. A significant Christian minority lived in the Chouf, however, and its return to the control of the state was a priority when Amine Gemayel came to power. Gemayel’s attempt to subdue the area was carried out not only by the Lebanese army, but also by the LF, who were in no mood to magnanimously establish a power-sharing regime with equal regard for all sides. These forces were led by the above-mentioned Samir Geagea, who established an LF presence (with Israeli approval) in the west of the Chouf in early 1983. The incursions were resisted by a coalition of Jumblatt’s PSP, along with the Communist party and the SSNP, essentially the core members of the LNM, which had dissolved following the Israeli invasion of 1982. This new coalition was known as the Lebanese National Resistance Front (LNRF), and while not members, was allied with Amal and also PLO elements who were beginning to re-emerge in the country following that organisation’s official withdrawal. The LNRF operated under the wing (I think this is an appropriate image) of Syria, just as their opponents were sanctioned by Israel. We need to constantly bear in mind this proxy war nature of the conflict as we go forward…or round and round in circles as the case may be.

Of course, this sub-war was not just about control of the Chouf. Fighting spread to the suburbs of Beirut and the whole thing took place against the backdrop of the American-led intervention and subsequent withdrawal, and the growing realisation by Muslims that the Gemayel government had little intention of reforming the political system in any serious way. Furthermore, Gemayel was proving reluctant to sign an accord (the so-called ‘May 17 agreement’) with Israel that would have given the Israelis a massive say in Lebanese affairs and alienated Syria. In order to twist his arm, Israel began to withdraw their support for the Christian forces in the Chouf, and without this support, the LNRF overran the army/LF positions in September 1983. The latter were forced to retreat, along with many Christian civilians, to the town of Deir el Qamar, where they were besieged until December. Those Christians in the Chouf unlucky enough not to escape were attacked by the Druze militia and a massacre of around 1,500 civilians in the area took place, not to mention the displacement of many thousands more from their homes.

At the same time, in west Beirut, Amal were fighting for control of sections of the city against Gemayel’s army, which was backed up by the MNF. American battleships in the Mediterranean fired shells at LNRF positions (although often missed and killed many civilians) and Reagan sent in extra troops, making increasingly belligerent statements about teaching Syria a lesson and unconditionally backing Gemayel. It is here you begin to see why they weren’t regarded as neutral peacekeepers by the Lebanese Muslims. The Americans’ French and Italian allies even expressed their concern that the MNF was coming to be seen as just another hostile foreign presence in the country, partial and combatant. It is against this backdrop that the suicide bombings discussed above occurred. By December, the Israelis had rescued many of the Christian fighters in the Chouf and Amal and its LNRF allies were proving more than a match for the Lebanese army in west Beirut. By early 1984 they had essentially driven Gemayel’s forces out of their part of the city and taken over. Berri even managed to convince Shia elements of the army to defect to Amal.

West Beirut came under the control of a number of different militias, who sometimes fought each other. It is basically in this period after the withdrawal of the MNF that Lebanon’s image in the west as an incomprehensible violent maelstrom of chaos really begins to approach the truth. A series of wars within wars within wars, as the various sects, once they had established control over their own areas, began fighting amongst themselves over the spoils of power. Law and order was replaced by the rule of brute force, protection rackets and summary executions. Any ideological or even sectarian dimension to the violence was often lacking and it becomes difficult at times to distinguish what was going from simple turf warfare between gangs.

The ‘War of the Camps’ was primarily between Amal and the PLO, as the Palestinian refugee camps in west Beirut were surrounded by Amal forces. These were heavily supported by Syria, who wished to prevent the PLO under Arafat from once again establishing itself as a major player in the war. The irrepressible Arafat, having fled the country in 1982, was back in Lebanon and Assad was haunted by the same old concern that it would provoke an Israeli invasion that would damage Syrian interests, and that it would become a rival locus of power. Using a number of anti-Arafat Palestinian factions who I won’t go into here (the last thing we need is more acronyms) Arafat’s partisans were attacked in their new headquarters in Tripoli in the north of the country, and their leader was expelled from the country for the second, and last, time, in December 1983.

This was not the end of the PLO’s resistance, however. In Beirut, Amal was not only supported by the Syrians but even a part of the Lebanese army commanded by Michel Aoun (more of whom later). Fighting centred around control of the Sabra and Shatila and Burj el-Barajneh camps and lasted sporadically between May 1985 and July 1988. The Palestinians were supported by a local Sunni faction which I haven’t mentioned yet, named Al-Murabitoun (‘The Steadfast’) and, belying any image of this as simply a Shia-Sunni conflict, Hezbollah who, in its rivalry with Amal, also took the side of the PLO. In the early stages of the conflict, Jumblatt’s PSP and its LNRF allies helped Amal defeat Al-Murabitoun, but were less enthusiastic about fighting the Palestinians, with whom they had a long tradition of comradeship. By the end of the conflict, they were in fact fighting alongside the PLO and Hezbollah against Amal. This seemingly-interminable conflict was only brought to its inconclusive end with the Syrian army’s direct intervention and occupation of west Beirut in 1987.

Despite the Syrian support for Amal, however, Hezbollah emerged ultimately stronger from the power struggle. In the west, its profile was raised by its association with numerous kidnappings of westerners in Lebanon from 1982 onwards. Like the embassy and barracks bombings, these were often carried out under other names such as Islamic Jihad in order to avoid direct responsibility, but it is generally accepted Hezbollah were behind them. Indeed many observers believe that Iran was ultimately pulling the strings. It is difficult to discern any other concrete motive to the kidnappings. The MNF had, after all, departed in 1984 and yet the seizure of Americans and European individuals continued unabated. Some have suggested that Hezbollah saw the kidnappings as insurance against renewed foreign intervention in the country, others that the Iranians saw them as a means of gaining leverage in backstairs diplomacy with the west. This latter objective can be seen in the secret Iran-Contra deals described in an earlier (part 4) post. The Iranians were ultimately responsible for getting Hezbollah to release many of the hostages, with the last, American journalist Terry Anderson, being let go in December 1991. This BBC documentary about Iran gives a good account of the whole affair. The bit about the hostage situation starts at 8:20.

If you keep watching to around 35:00 you realise the somewhat shabby treatment of Iran by the Americans. Having helped get their men released, the United States government then reneged on an promise to improve relations with Iran in return. Also, don’t miss the skulduggery of the French opposition, who apparently scuppered negotiations to release French hostages and paid Hezbollah to keep them until after the French election in order to help Jacques Chirac win.

Certainly these were not acts of random or mindless vengeance. To capture, keep hidden and keep alive a western civilian for years on end in war-torn Lebanon required a level of planning and military discipline that suggests a determined purpose. While it cemented Lebanon’s reputation in the west as a lawless hellhole, among the Lebanese Shia (and indeed across the Muslim world) it contributed to Hezbollah’s growing prestige as the true face of Islamic resistance to the west. Allegiance to Hezbollah was no doubt bolstered by the Israelis’ indiscriminate bombing of Shia villages in the south, and the continued covert involvement of the United States. The most notorious of these incidents was a car-bomb in March 1985 intended to kill the cleric, Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah, who was (wrongly) believed to be the leader of Hezbollah, for which the CIA and British intelligence are believed to have been responsible. It killed 80 civilians, mostly women and schoolgirls, and Fadlallah escaped with minor injuries. Such actions only fueled support for Hezbollah’s more radical message of resistance to Israel and the west.

Hezbollah’s prestige was probably most augmented by their leadership of the fight against the Israelis in the occupied south. While Israel had not withdrawn by the end of the civil war in 1990, Hezbollah effectively bogged them down in an unwinnable war of attrition which, for the first time, inflicted what could be described as a defeat on the IDF. Israel would finally withdraw in 2000. It is interesting to reflect that senior figures on both the Lebanese and Israeli side credit the Israeli invasion with the genesis and growth of Hezbollah. It’s current leader Hassan Nasrullah has said that, had Israel not invaded, ‘I don’t know that something called Hezbollah would have been born. I doubt it.’ The former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak, one of the more reflective of the political class there, also stated: ‘When we entered Lebanon … there was no Hezbollah. We were accepted with perfumed rice and flowers by the Shia in the south. It was our presence there that created Hezbollah’. This attests to a phenomenon which will be seen time and time again with other groups like the Taliban or Islamic State, which is the expansion of a small group of fundamentalists to a major actor in the conflict, not so much as the result of some homegrown rise in religious fervour as a response to the destabilisation of their country by outsiders.

While the Muslim groups were busy shooting at and blowing each other up, the Christian militias were showing they were every bit as capable as their Muslim opponents of internecine conflict. The agreement which would eventually bring the Syrians into Beirut again had been signed by the LF leader Elie Hobeika, but Samir Geaga didn’t support it, nor did Amine Gemayel, who was leader of the Phalangist party as well as being president. The LF split up into two factions, led respectively by Hobeika and Geagea, and fought a bloody and destructive conflict over whether to accept the accord or not. Geagea, who had the support of the Lebanese army and also maintained close ties to Israel (while Hobeika sought to break these ties) eventually emerged dominant and Hobeika fled to the city of Zahlé in the Beqaa, forming a rival LF under Syrian patronage.

Gemayel, meanwhile, was nearing the end of his term as President in September 1988. This being Lebanon, however, it wasn’t simply a case of the parliament meeting and electing a successor. The Syrian-approved candidate was the former president Suleiman Frangieh (yes, he’s still around; he was old the first time around, now he’s 78!) but he was unacceptable to Geagea’s LF faction (not to mention the Americans) and nobody could agree on an alternative. When a session was arranged to elect (i.e.crown) Frangieh, the Lebanese army under it’s commander Michel Aoun (below) was accused of preventing the delegates from east Beirut from attending, and thus preventing the session from reaching the quorum necessary to validate the election.

Rather amusingly, Aoun denies he prevented them, suggesting in interviews that they called him and asked him to prevent them from attending. The haggling went on so long that Gemayel’s term ran out without a successor being elected, so the latter appointed a military government headed by Aoun, who himself had wanted to be president but was opposed by the Syrians. He now became acting Prime Minister, or I should say at least one of the acting Prime Ministers, because Gemayel’s Prime Minister Selim Hoss refused to accept his dismissal, citing the National Pact, which reserved the post to a Sunni (Aoun is a Maronite) and set up its own rival regime in west Beirut with the support of Syria, dismissing Aoun from his position as commander of the armed forces. Aoun on the other hand had the support of most of the army, Geagea’s LF and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, which was seeking to extend its influence over the middle east (the invasion of Kuwait was less that two years away) where the local Ba’ath party were deadly rivals of the Syrian Ba’ath party. This alliance incidentally would alienate the Americans from Aoun when they became enemies with Saddam Hussein, and pushed them into supporting the Syrians’ role in the country.

The stage was set for the last major showdown of the civil war. Aoun declared a ‘War of Liberation’ from the Syrian occupation in March 1989 and a campaign of shelling between east and west Beirut followed in the next few months which was more destructive than anything yet seen in the war, which for Beirut is really saying something.

The Lebanese civil war lasted from 13 April 1975 and ended on 13 October 1990, that is, 15 years and 6 months. The death toll is often given at around 250,000 victims, although more recent research has greatly reduced this. I have seen estimates as low as 40,000, and am frankly at a loss as to how they can vary so wildly. Given the massive upheaval and suffering it involved, as well as its longevity, it is alarming how little really changed after all this. There was some slight reform to the political system as has been seen, but sectarianism remained a cornerstone of politics and Syria remained entrenched in Lebanese politics. The emergence of Hezbollah is of course a vital episode in the emergence of Islam as a force in middle-eastern politics, but once again we should reflect upon how little role religion played in the genesis of the war. It was only after years of suffering and, even more significantly I think, hopelessness, that an anti-western religious fervour was kindled, but this cannot be said to characterise the war as a whole, which had far more to do with problems specific to Lebanon than any broader conflict in the middle east as a whole. Because I think a picture says a thousand words, I will end this series on Lebanon with this picture of a man praying in the rubble of his own home in southern Lebanon, 1993, where the war against Israel continued sporadically to the present day.

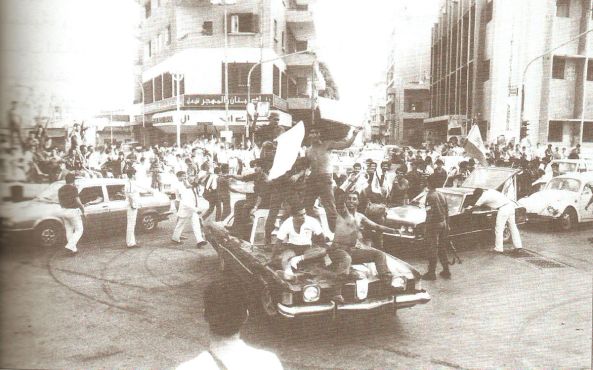

Featured image above: Amal militia members attacking the church of St.Michael, Beirut, 1984.

End of part 7