2

While the last post took us up to the early sixties, it is necessary to backtrack a bit in order to look at the events surrounding the creation of Israel. This is not intended to be an over-arching history of the Arab-Israeli conflict, but to take a look at how this conflict impacted on political developments in the Arab world and how western governments influenced the course of affairs. The previous post has sketched out the chaos which attended the British Mandate of Palestine in the inter-war years, and the failed attempts of the British government to reconcile the interests (and promises made) to both the Arabs and Jews in the territory. From the 1920s on, Palestine was wracked by inter-ethnic violence, as Arabs grew increasingly anxious at the growing influx of Jews from European persecution, and Jews sought to lay the foundations for a future state and circumvent the attempts of the British authorities to keep them out and prevent them from buying land.

One of the reasons for the violence and dislocation that attended the creation of Israel, and the fact that the Palestinians emerged with no state of their own, is the incompetency and sheer recklessness of the British withdrawal from the territory at the end of the mandate period in 1948. Materially exhausted by war, and with a public back home which refused to tolerate more overseas military adventures, the British government essentially washed its hands of Palestine and left it to the two sides to fight it out. A similar catastrophe occurred in India at the same time, as a hasty British withdrawal with little preparation (preceded by decades of fostering Hindu-Muslim divisions) led to the deaths of half a million civilians in intercommunal rioting. In Palestine, their attitude was summed up by the head of the British administration, who held a press conference on the day of their withdrawal; asked by a journalist to whom would he give the keys to his office, he replied: ‘I will leave them under the mat’.

A United Nations plan to partition the country in 1947 (and provide a separate international administration for Jerusalem) was accepted by most Jews (although there is good reason to believe it was merely seen as a stepping-stone to expansion of Israel to the whole of Palestine) but rejected by the Arabs. The British, however, refused to assist the U.N. in establishing the necessary institutions to execute the plan, or help in the smooth handover of power. They were lukewarm about the creation of a Jewish state (in retrospect it seems odd, but it was assumed at this time that any Jewish state would become a communist ally of the Soviet Union) and at the same time preferred the occupation of Arab lands by their Jordanian ally to the creation of a Palestinian Arab state. In short, the situation was a mess, with no-one to prevent the two sides from using force to establish their claims to land. A civil war had already been raging for some time by the time the British unilaterally withdrew in May 1948, upon which Israel declared itself an independent state. The same day, Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Iraq invaded to prevent its establishment.

The following map compares the proposed partition under the U.N. plan to the territorial division that eventually resulted after the end of this first Arab-Israeli war (1948-9):

As can be seen, Israel succeeded in establishing itself over an area even larger than that allocated to it in the partition plan. Space does not permit a detailed account of the war, only the first of several between Israel and its neighbours. To cut a long story short, it was a disaster for the Arab states. Although initially confident of victory, they were poorly-prepared, equipped and led, and disunited in their political objectives. While its allies were ostensibly fighting to establish a unified Palestinian state and prevent the establishment of Israel, Jordan had secretly agreed to occupy and annex to itself the West Bank alone, leaving Israel free to occupy the rest of Palestine. In return for his perceived treachery, King Abdullah would be assassinated by a Palestinian in 1951. Perhaps the decisive factor in the war was that, for fear of alienating the Americans, the British ceased supplying arms to the Arabs, while at the same time, the Israelis got massive quantities from Czechoslovakia.

American support, while it would later become overt, was initially subtle and hesitant. It was nevertheless vital. One of the key turning points was when, during the course of the war, a renegotiation of the partition plan was proposed which would undo some of the territorial gains made by Israel. President Truman, seeking re-election in that year, withdrew American support for this plan in order not to alienate Jewish voters in the United States. He was quoted as saying: ‘I have to answer to hundreds of thousands who are anxious for the success of Zionism. I do not have hundreds of thousands of Arabs among my constituents.’ Israel was effectively given carte blanche to seize with force as much of the former Palestine as it could. It is also indicative of the Arabs’ growing desperation that partition, which they had rejected, was now accepted as the basis for negotiations. Folke Bernadotte, the Swedish diplomat charged with mediating between the two sides, was murdered by the Israelis in order to scupper any deal and at the end of the war the Palestinians were rendered stateless, dispersed throughout the Jordanian-occupied West Bank, the Gaza strip (effectively under Egyptian control although a puppet-Palestinian authority was recognised there), living in huge refugee camps or stranded within the borders of Israel.

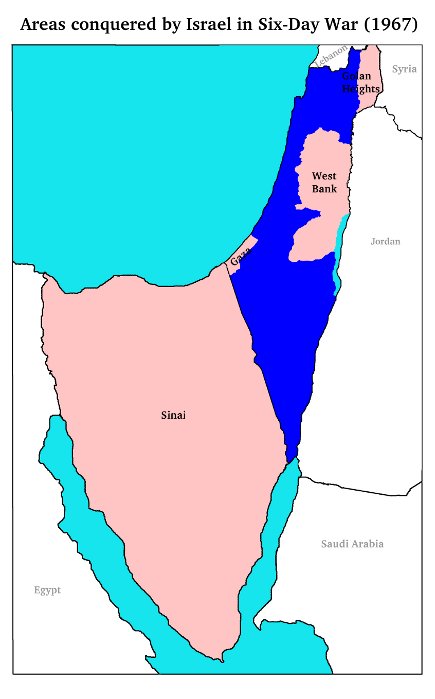

Developments in the Arab states neighbouring Israel in the years leading up to the next major conflagration (1967) have been covered in the previous post. The immediate catalyst for the war continues to be debated, with both Israeli and Egyptian defenders claiming the other side made the first aggressive moves. Basically, after years of tension, Egyptian belief that the Israelis were planning an attack caused them to mass troops on the border, the Israelis in turn interpreted this as preparation for an Egyptian attack, and therefore decided to take preemptive action. Having destroyed the Egyptian air-force in one fell swoop, the IDF took Gaza and the Sinai peninsula with little or no serious opposition. When Jordan and Syria were compelled to support Egypt, they too were attacked and the Israelis occupied the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Golan Heights in Syria. The Sinai would remain under Israeli occupation until 1982, when its withdrawal was agreed in exchange for the presence of a multinational peacekeeping force, which remains there to this day.

Once again the war was a humiliating disaster for the Arab enemies of Israel. For the Palestinian population, it was even worse. As many as a million people were displaced from areas conquered by Israel. Palestinians in the West Bank (many of whom were refugees from the first war) were compelled to flee to Jordan. Many remained within the borders of Israel but were denied citizenship or civil rights. Israel’s occupation of these territories (and building of settlements in) continues despite their illegality under international law and condemnation in numerous United Nations resolutions. Many who advocate a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestinian conflict see a return to the pre-1967 borders as the basis for any agreement in the future.

In keeping with the mainstream of Arab politics at the time, in the struggle for Palestine, religion and jihad played little role. The leadership of the Palestinians during the period of the Nakba (disaster) was itself uncoordinated and dominated by wealthy families who were bogged down by internecine power-struggles. They were led from the 1920s to 1948 by Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem (surely one of the great job-titles in history), an ostensibly religious authority which made him de facto head of the Palestinian Arabs. Here he is, hanging out with some Nazis:

As the above picture suggests, al-Husseini had some nasty bedfellows in his campaign against Zionism. Led to expect help from Nazi Germany in preventing the creation of Israel, he spent much of the war propagandising on their behalf and raising Muslim recruits. He approved of the Holocaust and made efforts to prevent Jews fleeing to Palestine to escape the gas chambers. Recent claims, however, made by Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, that Husseini gave the Nazis the idea of the Holocaust, are patently nonsense, and reflect instead an effort on Netanyahu’s part to somehow retrospectively blame the Arabs for the crimes committed by Germany. It is also an attempt to link modern Islamic fundamentalism with European fascism in some tangible causal sense, but there is in fact no material continuity between al-Husseini and modern jihadists.

The leadership of the Palestinians as personified by the Mufti was in fact shambolic and incompetent, and within a few short years of their defeat, al-Husseini and his cronies were thoroughly discredited among the Palestinian diaspora. While the Arab league recognised an ‘All-Palestine Government’ as covering the whole former mandate, their writ only ran in Gaza, and even there, power actually lay with the Egyptians. Nasser did away with the fantasy of Palestinian statehood and abolished the body in 1959. Within a decade, Gaza lay within the borders of Israel in any case. There now arose from the exiled Palestinians a new leadership. Once again, the political response from Arabs was a secular, modernising one with little reference to Islam or jihad. This new generation of Palestinian leaders emerged from the refugee camps set up by the U.N. or others scattered throughout the Arab world. Its inspiration was Nasserist nationalism and it was avowedly secular and left-wing, often with ties to either the Soviet Union or Maoist China. An umbrella organisation for the various factions within this new Palestinian resistance was set up in 1964. It was called the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, or PLO for short.

The leading group to emerge within the PLO was Fatah (a reverse acronym from the Arabic for ‘Palestinian National Liberation Movement’) which also translates as ‘victory’. It was founded in 1959 by Yasser Arafat, who became leader of the PLO as a whole in 1969. Fatah was typical of the new generation of Palestinian resistance: Arafat had been a student agitator in Cairo, and many of its other founders young professionals working abroad in either Egypt, Lebanon or the Persian Gulf states. Here is Arafat (sunglasses and all) speaking before the United Nations general assembly in 1974:

And here was the Israeli delegation’s reaction to him being given the opportunity to speak:

The PLO were at first based primarily in Jordan. Given Jordan’s annexation of the West Bank, as well as the influx of refugees from Israel, Palestinians came to constitute a huge proportion of Jordan’s population, and the aims and political values of the PLO and its supporters, who were more radical and had more in common with the proactive stance of Nasser, came into conflict with the cautious and pro-western policies of the Jordanian king, Hussein:

Hussein had been present at the assassination of his grandfather Abdullah in 1951, and presided over one of the regions best-equipped and best-trained armies, a legacy of the extensive military assistance Jordan had received from the British, in return for which they acted as a brake on more independent-minded rulers like Nasser. At the same time, defeat in the 1967 war had damaged the prestige of the Pan-Arab movement and its leaders, and Palestinians increasingly turned to the PLO and Arafat for leadership instead of Nasser and the older generation. The PLO became so powerful and significant a presence in Jordan throughout the 1960s that they were practically a state within a state. King Hussein acted in 1970 to expel them, in a conflict that was to become known as ‘Black September’. This left thousands of PLO members dead and its leadership expelled to Lebanon. The PLO had received support in the conflict from the Syrian government. Indeed, it was probably the Syrian army’s withdrawal under attack from the Jordanian air force, which proved decisive to the outcome of the war.

Egypt

This is as good a place as any to pick up the threads of the story in Egypt and Syria where we left it last time, with both countries re-emerging from their failed union of 1958-61. Gamel Abdel Nasser remained as popular as ever despite the failure of the UAR and its denting of hopes for Pan-Arab unity. The fallout from defeat to Israel in 1967, however, seriously damaged the prestige and credibility of not only Nasser, but secular nationalist leaders throughout the region. The effect was, however, not immediate. Nasser attempted to resign after the Six-Day War, but massive protests compelled him to rescind his decision the following day and he remained in power. These events nevertheless, as well as the economic hardship that lay ahead in the 1970s, can be seen to mark the beginning of a growth in Islamist sentiment, as the secular nationalists were perceived to have failed.

Such a strain in political thought was of course nothing new, but up until now it had been confined to a small minority of activists and contained by state security. The 1970s saw a surge of support for the Muslim Brotherhood and, subsequently, less peaceable groups. In response to state repression, this militant, jihadist tendency within Islamism would grow in importance throughout the decade and claim as one of its ideological grandfathers a man arrested by Nasser’s government in 1954 and executed 12 years later, Sayyid Qutb:

Qutb had worked as an official in the ministry of education and a visit to the United States in the 1950s had convinced him that western civilisation was poisonous-threatening to blind the masses from the truth of Islam by its seductive materalism and pandering to the individual’s selfish desires. On returning to Egypt in 1950 he became convinced that his mission was to save the Muslim world from this influence, which he already saw creeping into Egyptian society. He joined the Muslim Brotherhood in 1953, who initially welcomed Nasser’s takeover of power in the mistaken belief that it would usher in the Islamification of government. When Nasser’s secularist convictions became apparent, the Brotherhood turned against him and, following an assassination attempt, many members were rounded up, imprisoned, and routinely tortured. Qutb was among them.

His horrific experiences in prison had a radicalising effect on Qutb’s philosophy, and he wrote and published many works (often smuggled out) arguing that much of what was described as the Muslim world was no longer, in any real sense of the word, Muslim. Its state Qutb described as jahiliyyah, comparing it to the spiritual condition of the pagan Arabs before the coming of Mohammed. The ruling elite came in for particular opprobrium from Qutb and his followers; it was argued that leaders like Nasser were actively working to undermine Islam and promote western values in their lust for power and wealth, and were no longer Muslims. As infidels, they could therefore be killed. It is this strain in Qutb’s thought that makes him so important to the development of militant Islam in the coming decades. It marks a crystallisation of a logic that would be used by jihadist groups to bypass the injunctions in mainstream Islam against killing, and argue that the means (saving Islam) justified the end and that its enemies could legitimately be killed.

Qutb was released in 1964 but rearrested the following year, when another plot to assassinate Nasser was discovered. In 1966 he was put on trial and his own publications were used to convict and sentence him and other Muslim Brotherhood members to death. This is a postage stamp, issued by the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1984, commemorating Qutb’s trial and execution:

Not surprisingly, Nasser’s government turned Qutb into a martyr for radical Islamists in the coming decades. It is tempting to wonder how different things might have been if the authorities in Egypt and other countries like Syria (see below) had conciliated the more moderate elements in the Muslim Brotherhood at this stage. The radical jihadists whom Qutb inspired had little in common with the mainstream of the Brotherhood, which enjoyed enormous popularity (the very reason the government feared and suppressed it) with the people, on account of its extensive charity work, free clinics and appeal to popular piety. The Brotherhood offered people a way into the political process that was otherwise blocked to all but the economic elite. It recruited its members from lower middle- and working-classes, whom no-one else seemed to care about. It was more successful in reaching out to the poor than the left, which tended to attract academics and intellectuals who had little in common with actual workers. In fact, aspects of their social policy had much in common with socialism. The Muslim Brotherhood was also gradualist in its approach to political change, ultimately aiming at the infiltration of Islamic thought into political life, but looking to achieve this through electoral politics and social influence instead of revolution and armed struggle.

The fact that Nasser’s, and other governments, closed off these channels of activity no doubt convinced younger Islamists that such regimes could only be challenged by violence. It is important that we recall this when we consider the militant direction which political Islam took in the 1970s and 80s: from North Africa to Iran, it was the secular, apparently ‘moderate’ governments, backed by western powers, who were running police states, torture prisons and committing massacres. From the point of view of ‘the masses’, the Islamists probably represented a more humane and moderate prospect than western-style secularism. The mass-appeal of political Islam in the 1970s to young people in countries like Egypt and Iran cannot simply be dismissed, as it so often is, as some kind of fanatical mass hysteria. It was certainly a reactionary, conservative response to social pressures, but it is far from inexplicable. Likewise, the fact that elements within it turned to violence in the face of government repression is neither strange nor unusual. To ascribe all this to sheer religious fanaticism is wilfully blind, and yet it is a narrative that has been consistently pushed in much of the western media.

The textbook example of this process is Iran. We will examine the Shah’s regime in due course but Sadat’s Egypt is an equally good example, differing from Iran only in that the Islamist revolution failed. We do not have to look far for sources of discontent towards the elite in 1970s Egypt. After Nasser died of a heart attack in 1970, power passed to his long-time ally Anwar Sadat (below) who, although he initially declared his intention to continue Nasser’s policies of Arab socialism and military co-operation with the Soviet Union, would steer Egypt in a radically different direction after defeat in yet another war with Israel in 1973. Once again, this is not the place for a comprehensive discussion of this conflict, the Yom Kippur War (sometimes known as the Ramadan or October war), in which Egypt and Syria launched an attempt to recover the Sinai and Golan Heights lost in the previous war. Once again, the Arab states failed in their strategic objectives, despite initial successes, and the Israelis pushed them back.

The war did, however, convince Israel that some kind of diplomatic accommodation would have to be reached with its Arab neighbours, and in the following years, a peace process was initiated with Sadat, which would eventually lead to the return of the Sinai to Egypt and the latter’s recognition of Israel’s ‘right to exist’. This detente with Israel was only one part of a series of radical changes to Egyptian policy made by Sadat at this time. The war also co-incided with a lessening of Soviet influence in Egypt which had begun in 1972. Egyptian army officials had become increasingly alarmed at the numbers and influence of Soviet military advisers in the country, with many arguing that Egypt was simply being used as a Soviet base in the Mediterranean. Over the coming years, Sadat sent back the Soviet advisers and turned towards the United States for support, both economic and diplomatic. Social policy was accordingly altered, with Nassertist state intervention and protectionism replaced by what was termed intifah, an ‘open door policy’ which encouraged the influx of foreign capital and loosened restraints on economic activity within the country.

This had the effect of enriching foreign investors and a small Egyptian elite, but it also dismantled whatever social safety net had existed beforehand. Lack of regulation meant speculation in the property market and other areas went unchecked, with correspondingly high prices and rents. In order to secure loans from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, for example, Egypt was compelled to withdraw subsidies on basic foodstuffs, although massive riots in 1977 forced them to backtrack on this measure. The clientist nature of Egyptian political life was not reformed to any great extent, with the result that this new ‘free’ market was presided over by a corrupt bureaucracy that awarded contracts and opened doors in return for bribes and other favours. Sadat presided over a kind of crony capitalism that left the vast majority of Egyptians disenfranchised, hungry and angry. It looked with resentment upon the small elite of oligarchs that benefited from all this, and associated the westernising influences sweeping the country with their greed and corruption.

Instead of looking towards western solutions such as socialism, therefore, many younger Egyptians looked to the one group who appeared untainted by all this and to offer indigenous solutions, the Islamists. The 1970s in fact saw some attempt by Sadat at reconciliation with the Islamists. Many Muslim Brotherhood members were released from prison and limited political activity permitted. The Brotherhood alienated many younger Islamists by explicitly renouncing violence and revolution at this time, and many students were funnelled into more militant groups such as Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (the Islamic group) which Sadat, seeking to counterbalance the threat of leftist enemies, actually encouraged and patronised in the early seventies until it grew into a mass movement and a threat to him. Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya was an umbrella group for militant Islamist groups such as Egyptian Islamic Jihad, which sought the violent overthrow of the Egyptian government and the institution of an Islamic state.

Sadat finally realised at the end of the 1970s that he had let the genie out of the bottle in encouraging these more radical Islamic groups. The Camp David Accords with Israel were viewed by the Islamists as shameful and a betrayal to the Palestinians, and they hatched a plot to assassinate Sadat and other prominent officials in the government, seizing control of the army headquarters, radio and television stations, in the belief that the masses would spontaneously rise up in revolution against secular authority. Sadat in turn realised political Islam had to be bottled up again and struck first, dissolving Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya and arresting members of Islamic Jihad, some within his own army. One cadre of jihadist officers was missed by the swoop, however, and in October 1981 they succeeded in killing Sadat at a military parade:

What followed was a profound disappointment to the Islamists, however. Instead of rising up in support of their revolution, the population remained calm and quiescent, as power was transferred smoothly to the vice-president, Hosni Mubarak, and hundreds of Islamists were rounded up and arrested in the weeks ahead. The assassins were tried and executed quickly. Hundreds of middle-ranking members of Islamic Jihad were dealt with in a mass-trial, and treated with surprising leniency, given jail sentences of a couple of years at most. These jihadists appointed as their spokesperson in prison a thirty year-old doctor named Ayman al-Zawahiri, who as a teenager, had formed a club with his friends the day after the execution of Sayyid Qutb, dedicated to establishing an Islamic state. This is al-Zawahiri at the trial:

Al-Zawahiri would go on to become a key figure in Egyptian Islamic Jihad, in itself a central part of the international network of jihadists who would come to be known as Al-Qaeda. He is today its leader, hiding somewhere in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region with a $25 million reward offered for information about his whereabouts. This is, needless to say, not the last we will hear from him. Al-Zawahiri and many of the other Egyptian jihadists were released from prison in the following years and slipped out of the country. Egypt was clearly nowhere near ready for the kind of revolution they proposed and, in any case, there was a far more urgent need for their manpower in another country where the battle between western secularism and Islamic would come to be defined in the 1980s, Afghanistan. There, the Egyptians would form the core of a foreign contingent of fighters alongside the Afghan Mujahideen, hone their military and propaganda skills, and when the war against the Soviets was won, prepare the way for a spreading of the war to the world at large. But that is a story for another post.

Perhaps an even more significant consequence of the failed Islamist uprising in Egypt was an ideological one. The shocking realisation that the masses were not ready to rise up with them led some to the conclusion that these masses were living in a state of jahiliyyah as described by Qutb. Just as they had come to the conclusion that such leaders might justifiably be killed, more radical Islamists came to include anyone, even civilians, who stood in the way of the establishment of Allah’s sovereignty over the state, as a legitimate target. This would have profound consequences for the future of those militant tendencies within political Islam. Once again, however, it must be stressed that these were a small minority within the Islamist political spectrum as a whole. In Egypt under Mubarak, for example, the Muslim Brotherhood was an explicitly constitutional and peaceful organisation. Its activities were severely curtailed by Mubarak, who was effectively a dictator, and yet it represented the closest thing the country had to a political opposition, its power resting on the kind of social work and connections to poorer Egyptians that had always ensured its popularity.

Syria

The suppression of Islam as a political rival in Egypt was relatively benign in Egypt in comparison to Syria, where its great nemesis would emerge in the 1960s, the Ba’ath party. This was a force that would come to play a vital role in the histories of both Syria and Iraq in the coming decades, and it is worth examining its origins for this reason. Ba’athism (‘resurrection’ or ‘rebirth’) was an Arab adaptation of enlightenment thought, socialist in character, seeking to fight foreign domination and overcome ethnic divisions and forge a concrete, Arab political identity. Its intellectual formulator was Michel Aflaq, a Syrian Christian who not only theorised the movement but would take part in its takeover of power in Syria.

Although not a mass movement, the Ba’athists emerged as a power within the army after the break-up of the union with Egypt in 1961. The UAR had initially been welcomed by the Ba’athists, who shared Nasser’s vision of Arab political union, but Nasser did not reciprocate the admiration, seeing them instead as a threat and banning their party. This essentially turned the Ba’athists into rival Pan-Arabists instead of allies. A military coup dissolved the union in 1961, although this handed power back to the old elite that had run the country before the union. In the army, however, a group formed which was influenced by Aflaq’s ideas, called the ‘military committee.’ These Ba’athists plotted a takeover of the country and admitted Aflaq into their conspiracy, despite his misgivings about seizing power by force. With hindsight, the committee’s two most significant members were the above Salah Jadid (above) and Hafez al-Assad. Here is Assad, pictured at the time he took sole power in 1970, and later in life on a Syrian banknote, as president…for three decades.

When the military committee went into action in 1963, they quickly took control of the country. Civilian figures like Aflaq were used to legitimise their rule for the first few years, but there was no doubt that the power really lay with the officers, between whom internecine conflict followed in the next few years as they struggled for power. A further coup in 1966 was a vital turning point. The military element, led by Jadid, sidelined the civilian, and ditched most of the distinctive Ba’athist goals like Pan-Arab unity, focusing instead on a strong centralised and socialist state. Aflaq and others, who continued to be regarded as the custodians of Ba’athist ideals, fled to exile in Iraq, where the local branch of the Ba’ath party had also seized power in 1963. Aflaq would spend decades in Iraq, and was treated like royalty by the regime there, proud to be seen as the protector of Ba’athism’s founder. Here he is on the left in 1988, shortly before his death:

The dude sitting next to him…we will get to him later. One thing at a time.

Back in Syria, the ‘Neo-Ba’athist’ regime, now more closely than ever allied to the Soviet Union, embarking on a series of radical reforms, reforms which proved too radical for the liking of Hafez al-Assad, who was slowly coming to wield unrivalled control over the armed forces. It was in these dying months of Jadid’s regime that Syria’s intervention in the Black September conflict, described above, took place. The failure of that initiated a crisis within the party and Assad seized power in November 1970, jailing Jadid and his leftwing associates, and initiating what is referred to as the ‘Corrective Movement’. If that sounds sinister, it should. In the beginning, however, Assad’s reforms looked modest enough, rolling back on the left-wing policies of Jidad’s regime and reaching out to private capital. He moved to reduce the influence of the Soviet Union. Supporters of Aflaq were wooed (although the breach between Syrian and Iraqi branches of the Ba’ath party was never healed) and an attempt made to improve diplomatic relations with other Arab states, which had deteriorated under Jidad.

Perhaps most radically, Assad abandoned the non-sectarian principles of Ba’athism in an astonishingly blatant way. Syria is a country in which Sunni Muslims constitute about 75% of the population. The Alawites, a Shi’ite sect to which Assad’s family belongs, make up roughly 12% of the population, but came to dominate the ranks of the civil service and army after Assad had purged it of potential threats. On the whole Assad’s objective was to create a centralised and authoritarian state devoted to keeping him in power, Ba’athist only in name. A parliament existed, but Assad could veto any decision it made. This sham democracy was complete with ‘opposition’ parties which were all controlled by Assad. The exception to this, and the only significant real opposition (again, even though it was officially banned) was the Muslim Brotherhood.

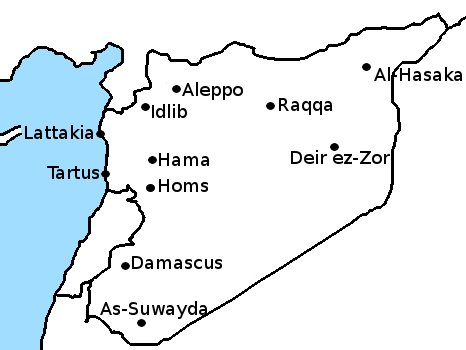

A map of the major cities in Syria might be useful at this point:

The Syria branch of the Brotherhood had been founded in the 1940s by Mustafa al-Siba’i, an Islamic jurist who agitated against French colonial rule. Instead of developing along the political lines of other campaigners for independence, Al-Siba’i, who came from a religious background, fell under the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood and its founder in Egypt, Hassan al-Banna. This is the only image I could dig up of al-Siba’i:

Al-Siba’i attempted to promote a combination of socialism and Islam, despite the hostility of many clerics to left-wing ideology (and vice-versa). The Brotherhood, except for repression during the period of union with Egypt, took part in legitimate politics throughout the period between the winning of independence and the Ba’athist coup. In 1961, it achieved its best result ever, winning 10 seats in parliament. When the Ba’athists took over, the movement was banned, although its leadership in the 1960s rejected the use of violence against the government in fighting repression. The fact that violence had to be explicitly rejected by its leaders, however, suggests that there were elements within the movement who were creating pressure for such an approach. By the 1970s, and after a violent crackdown on Islamists by Jadid, which occurred around the same time as Nasser’s executions of leaders like Qutb in Egypt, the pressure for a more aggressive response from the Islamists was becoming intense. This faction was based in Aleppo and Hama, and led by Abdel Fattah Abu Ghuddah, here on the left:

This faction gained influence partly because the regime violently repressed even the moderates. In 1980, membership of the Brotherhood would be made a crime punishable by death. A new movement emerged to organise resistance to the government, which was linked to the Aleppo-Hama branch. It was called the Fighting Vanguard (Talia al-Muquatila) and promoted a radical solution against the Assad regime, justifying the killing of Ba’athist party officials and military personnel in the belief that they were conspirators in a Sh’ite plot against the Sunni Muslims of the country. Its founder, Marwan Hadeed (above right) had been radicalised by the brutal suppression of protests in Hama in 1964, when the army killed up to 100 civilians and bombed the local mosque. Hadeed would be killed in prison in 1975. Complete with a suitable martyr, his organisation went from strength to strength, attracting in particular young men who were impatient with the passive and conciliatory approach of the Muslim Brotherhood’s moderates.

The military confrontation between the government and the Islamists intensified towards the end of the 1970s, with atrocities by one side provoking an even greater atrocity by the other. The Fighting Vanguard became less discerning in its choice of victims. A leader from Aleppo became greatly influential in this regard, Adnan Uqlah:

Uqlah organised a massacre of cadets at a military school in 1979 which, if the army had been hesitant about persecuting the Islamists before, steeled them for the harsh measures that lay ahead. He opened up the movement to larger numbers, usually young men under 20, zealous for action but often immature and poorly-trained. Some within the movement blamed him because they hadn’t the resources to train these new recruits and it left them open to indiscipline and infiltration by Assad’s secret police. Uqlah himself was arrested and basically disappeared off the face of the earth-no doubt killed just like Hadeed.

Another major turning point came in 1980, with the attempted assassination of Assad himself. Grenades were thrown at him during a diplomatic function but somehow the president cheated death. The next day, the security services executed an estimated 1000 prisoners in Tadmor Prison in retaliation for the attempt. Tadmor, located near the ancient ruins of Palmyra in the desert east of Damascus, was (and would continue to be) a byword for state terror, as the prisoners of Assad’s regime were routinely tortured and killed there with impunity. It is interesting to reflect that when ISIS captured the prison in May 2015, having released videos showing the prison’s harrowing interior, they promptly destroyed the building and released footage of its ruins:

The prison massacre was one more grisly milestone in the escalation of the conflict, which would culminate in the attack on the city of Hama in 1982. This put a decisive end of the conflict in a way that would resonate with Syrians to this day. The sheer scale of the destruction was clearly intended to send out a message to the Syrian people that no opposition to the Assad regime would be tolerated.

Hama was the epicentre of resistance in Syria. The year before had already witnessed a massacre in the city, as the army retaliated for an attack on a security checkpoint by killing at least 350, chosen randomly from the city’s population. This inability to distinguish between friend and foe, the categorising of the entire population as hostile and legitimate targets, characterised the Assad regime, and in the following year, Hama would witness an even greater atrocity. The army, led by Rifaat al-Assad, the president’s brother, arrived at the beginning of February and were attacked by the insurgents with heavy casualties. Islamists in the city then turned on Ba’ath party officials and workers in the city and killed an estimated 70 people. It was decided to deal with the Islamists in the city once and for all and send out a message to their allies all over the country. A cordon was established around the entire city and for three weeks not only the insurgents, but the civilian population, was massacred, with the deaths of between 10-40,000 people. Much of the city was razed to the ground, ostensibly in order to make way for the army’s tanks. Notorious incidents, such as the burning alive of 75 people in the Halabiyyé district, would remain seared in the memory of all Syrians, which was no doubt the intention of Assad in performing this exemplary punishment. Hama brought an end of the Islamist uprising in one fell swoop.

No doubt on account of this thorough repression, political Islam disappeared underground in Syria to a great extent in the next two decades. Assad continued the process of building a highly-centralised authoritarian state that had much in common with countries behind the iron curtain. Even after the fall of ‘Communism’ in eastern Europe, Syria, despite making a few concessions to encourage private investment in the economy, changed little. A cult of personality was encouraged around not only Hafez al-Assad, but his entire family, and the ground prepared for the succession of his son, Bassel (below, standing in the middle). Unlike other leaders like Muammar al-Gaddafi or Saddam Hussein, who liked to flaunt their military image, Assad projected an almost boring, managerial image. Here is a picture of the whole family taken in the early nineties. They look like a firm of accountants. Current president Bashar al-Assad is standing second from the left. He became heir-apparent when Bassel was killed in a car crash in 1994.

This image is interesting, because despite the mild, middle-management image, Assad’s regime was as militarised and ruthless as any in the region. To outside observers, the image of religious fanatics baying for the blood of hated infidels, and killing with apparent indifference to the identity of their victims, often made the rivalry in countries like Syria appear a rather simple one, between extremists on the one hand and moderates on the other. If we look closer at the reality of life for the majority of the population in countries like Syria and Egypt, however, it was the besuited, mild-mannered and secular authorities touting ‘progressive’ western values who also happened to be the practitioners of brutal state terror and repression.

This may help to explain a phenomenon so many in the west have found inexplicable: that in the latter decades of the twentieth century, so many people in Muslim countries turned towards political Islam for solutions to the challenge of the modern world. Beyond those with a specific interest in the Middle East, this fact went largely unnoticed in the west until it burst onto the world stage in 1979, in a country where the Islamists’ dreams of a people’s uprising and institution of an theocratic state came to realisation: Iran.

End of part 2

Feaured image above: Eyes of Hafez al-Assad, detail from a propaganda mural, 1970s Syria