Kosovo has already been mentioned a few times in the previous post on Bosnia, but I feel it deserves a post of its own here because I didn’t just want to bracket it off as if it was a sideline to the ‘main’ conflict between Bosnia and the Serbs. It wasn’t. The conflict in Kosovo has its own dynamic and really needs to be examined discretely, while recognising the obvious connections between it and the other conflicts that have raged in the former Yugoslavia. One similarity with Bosnia is the obvious Serbian connection. Many of Bosnia’s problems during the breakup of Yugoslavia were a result of the complex ethnic composition of its population, specifically a large Serb minority scattered (if more concentrated) in the north and west of the state. Although ethnic cleansing simplified things in its own brutal way, the absence of clear geographic boundaries along which to draw borders created much of the chaos, uncertainty and fear that fueled the conflict. Kosovo too had its Serb minority. In the years leading up to the showdown of the 1990s, its fate was, if anything, loaded with even greater symbolism and meaning.

While this blog is supposed to be a history of Muslims peoples, and while I am focusing on the Muslims of south-east Europe at the moment, there is no getting around the fact that this story is going to be as much a story of Kosovo’s Serbs as it is of Kosovo’s Albanians. While Serbs are now a minority in Kosovo, this was not always so. More than this, as alluded to in the last post when discussing the Battle of Kosovo (1389), Kosovo holds a special place in the Serbian national imagination that has led to it being described as ‘the cradle of their civilization and their Jerusalem’. (Judah 2008, 18) This raises many questions: how can this be, if there are so few Serbs there now, and if there were many more in the past, what happened to them? None of the answers to these questions are undisputed, and I am treading into an area which many are likely to disagree (sometimes violently) on. So be it. All I can do is try and give a synthesis of what I think are the most reputable and unbiased accounts that are backed up by some kind of evidence.

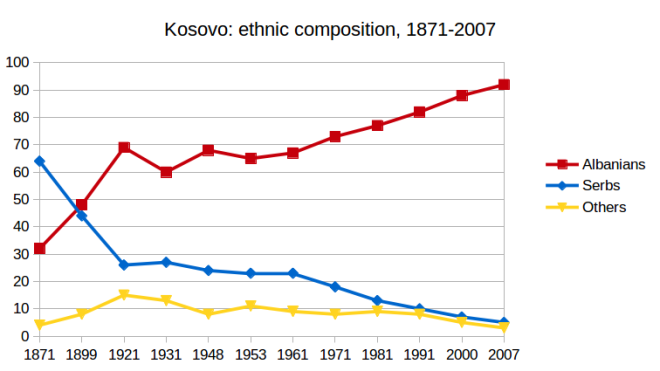

The above chart lays out, in mundane-looking statistics, a fairly dramatic demographic shift in the ethnic balance of Kosovo’s population in less than 150 years. There seems to be broad agreement about the figures, but as regards the story behind it, almost nothing is agreed on. As we noted when discussing the 1389 battle, what people believed and believe happened in the past is, when it comes to Kosovo, as important was what actually did happen. Whatever that was.

To return to the fourteenth century, it has already been noted that the Serbs and their allies lost this famous battle against the Ottomans on Kosovo Field (Kosovo Polje, Косово Поље, in Serbian; Fushë Kosovë in Albanian), the ‘Field of Blackbirds’, just west of the modern-day capital of Pristina, but that this loss became the centrepiece of a story that became crucial to the Serbs sense of their own identity as a people. The loss at Kosovo, where the relatively-small Serbian-led forces gave one of the most powerful empires of their day a run for their money, became the subject of a powerful idea: that in losing the battle, the Serbs had heroically sacrificed the earthly kingdom for the heavenly one and were, as such, a sort of chosen people, that they would rather die honourably that live under the yoke of Ottoman rule, and that one day the Serbian nation would be redeemed and rise up again to take its place. What is important to remember though is that this idea only gained potency and agency in the nineteenth century, as the modern Serb state was beginning to define a sense of its own nationhood and free itself from Istanbul.

This does not necessarily mean this was a modern invention; it was clearly the subject of folklore and song for a long time before this, but it was in the nineteenth century that these stories were transcribed and given context by Vuk Karadžic, the philologist and folklorist who was instrumental in the codification of the modern Serbian language. What emerged is what its detractors call the ‘Kosovo Myth’, in which the modern Serbian nation was essentially born on Kosovo field and established its legitimacy there. Whether or not you subscribe to it, it is hard to ignore the fact that the modern Serbian nation established itself in leaps and bounds in the nineteenth century, and it had nothing to do—causally speaking—with a fourteenth-century battle. Modern Serbia fought its way to independence first with a revolution starting in 1804 which led to autonomy as the Principality of Serbia, which led in 1882 to full independence as the Kingdom of Serbia, which would last until 1918. The association of Kosovo with Serbian nationhood and honour reached fever-pitch at the 500th anniversary of the battle in 1889. But there two awkward facts that complicate matters here: firstly, Kosovo was not a part of Serbia at the time (it remained under Ottoman control) and secondly, this was precisely the period in which the biggest dip in Serbia’s share of the population in Kosovo occurred.

This was not the first exodus of Serbs in the face of Ottoman power. Earlier waves of emigration in the 1690s and 1730s have gone down as the ‘Great Migrations’ of the Serbs, occurring following periods of brief Habsburg occupation of areas which were then re-taken by the Ottomans. The 1690s purportedly saw the Habsburg emperor, Leopold I, invite the Serbian Orthodox patriarch to lead his people out of Ottoman-reoccupied areas such as Kosovo, and settle in areas under Austrian control, especially the area of northern Serbia today known as Vojvodina, and an area traversing the borders of modern-day Bosnia-Croatia-Serbia known as the Krajina (meaning ‘frontier’ or ‘march’), a term that will come back to haunt the region in the 1990s, but what at that time denoted the militarised borderlands between the Habsburg and Ottoman empires, in which Christian Serbs and Croats were offered land by the emperor, in return for which they were obliged to fight for the Austrians and defend the area from the Turks, thus establishing a kind of buffer zone between the two empires.

The idea of a dramatic exodus of Serbs from Kosovo has not gone unchallenged, however. There is always some smartarse who says ‘ah but things are more complicated than that’, and it may very well be that they were. One of the foremost English-language specialists on Kosovo, Noel Malcolm, has argued that the simple story of Serbian flight in the face of Ottoman advance is misleading, and that things were more complicated: for example, that some Serbs fought on the Ottoman side, while some Muslims fought for the Habsburgs. Not only that, but large areas of Kosovo were already mainly Albanian/Muslim before this supposed migration, and that many of those Serbs who headed north came from other parts of Serbia. So this is debated, and I don’t consider myself qualified to adjudicate who is right or wrong, except to note that it continues to be disputed.

We are on firmer ground, though, when we come to the later nineteenth century and the period around which Serbia achieved recognition as an independent kingdom, following the Congress of Berlin in 1878. The same congress saw the creation of the Kosovo vilayet (a first-level administrative division of the Ottoman Empire), which became (with Serbia formally lost and Bosnia occupied by Austro-Hungarian troops) the Ottomans’ last redoubt in the Balkans. The Serbian–Ottoman War immediately preceding Berlin saw as many as 70,000 Muslim Albanians flee to Kosovo. Serbs were flooding out of the area at the same time, partly driven out by Albanians, but also encouraged to move to the newly-independent Serbian kingdom with the promise of safety and free land. It seems likely that it was some time in these years that the demographic balance in Kosovo tilted in favour of Albanian-speaking Muslims.

It is indeed high time something be said of the Albanians at this point. In a way, I feel I should go back and revise some of what I have written when I realise that I am nine paragraphs in and have hardly said a word of qualification about this nation and its people, their historical origins, and what they believe their historical origins to be. But on reflection, I think I will leave things as they are, because in a way it’s fitting that we arrive tardily at some kind of clarification, because the Albanians themselves were latecomers to the nationalist merry-go-round of nineteenth-century Europe. It is difficult to come to a definitive explanation as to why this is. It may be that, being mostly Muslim, the Albanians did not suffer the same disabilities under Ottoman rule that Christian subjects did. In the Ottoman system, a person’s ethnic and social identity was synonymous with their religion, so religion lent Muslim Albanians some degree of identity with their rulers. (Vickers 1995, 14) None of this, incidentally, is to imply centuries of peaceful quiescence under Ottoman rule in Albania; there were numerous famed rebellions against the Turks, especially those in the fifteenth century led by Skanderberg, who has become a national hero in Albania, but we don’t have time to go into all that. Perhaps in a separate post focusing specifically on Albania someday.

When modern Albanian nationalism did emerge—with a declaration made at Prizren in 1878 for greater autonomy within the empire—it was not conceived of as something novel by the Albanians, but as a ‘rebirth’ or ‘reawakening’ of the nation of Skanderberg. In reality, it was more as a reaction to Serbian and Montenegrin national movements than a chafing at the bounds of Ottoman control, and it was around language rather than religion that it crystalised. Modern Albania, unsurprisingly after a half century under Communist rule, is markedly secular in character and religion has really played little role in its modern history. Even in the pre-modern era, the form of Islam practiced in this area was generally a laidback Sufi brand of Sunni Islam. (Judah 2008, pp.8-9)

There is also the fact that, while Muslims have formed a majority since the sixteenth century, there have remained significant Catholic and Orthodox minorities. Living on the religious fault-line between Christendom and Ummah, Albanians seem to have been loose in their religious affiliations. Travelers in the nineteenth century recorded their impressions of Albanians hedging their bets, so to speak, and attending both the mosque on Fridays and church on Sundays, as well as whole villages changing their faith according to the prevailing political power. (Vickers 1995, 16) On the whole, Islam does not seem to have played as central a role in Albanian identity-formation as the Orthodox church did in Serbian, or Catholicism did in Croatia. This is important to bear in mind as we focus on the modern conflict in Kosovo, where Islam, and religious fundamentalism, have been insignificant as a factor in a conflict that has been fueled almost entirely by nationalism, language and ethnicity.

Perhaps at the end of the day, most Albanians’ primary focus of identification (at least among the rural population who were the vast majority) at this point in time was not a religion or nation or a language, but the fis or tribe/clan, with an elderly male at the head, existing in defiant independence of any higher authority. Add to this the difficult communications due to natural geographic barriers, it is not surprising it took some time to cohere into a national unit. What, you may ask, has all this to do with the modern conflict in Kosovo? We have already looked at Serb claims to Kosovo as the ‘heart’ of their nation, despite the scarcity of Serbs remaining there today. As Noel Malcolm has pointed out, many of the most important milestones on the road to Albanian independence took place in Kosovo, and their national story is important in understanding the Kosovar Albanians’ claims to the area. (Malcolm 1998, 217) Indeed, these claims go further back than the Ottoman era, ultimately being founded upon the view that the Albanians are descended from the people known, at the time of the Roman Empire, as the Illyrians.

The Illyrians’ presence in the area, before the Slavic people who migrated into the Balkans from the sixth century onwards, is a central part of the claim that Albanians inhabited Kosovo before the Serbs, and that even though they lost control of the area in the Middle Ages (never mind the fact that it had been conquered by the Bulgarians and the Greek Byzantine empire too), they had prior claim. The Albanian national movement of the late nineteenth century, therefore, included Kosovo in its claim to an Albanian nation, although initially, they limited their demands to autonomy within the Ottoman empire as a united vilayet. As we have already seen, Kosovo was already a separate vilayet, while the area that is now Albania (see above) was divided into several different vilayet: Shkodër, Manastir and Janina, where Albanian-speakers were mixed in with other ethnic groups. The Albanians’ hope was for a vilayet consolidating all of these regions, including Kosovo, and this was under negotiation in 1912 when the First Balkan War broke out.

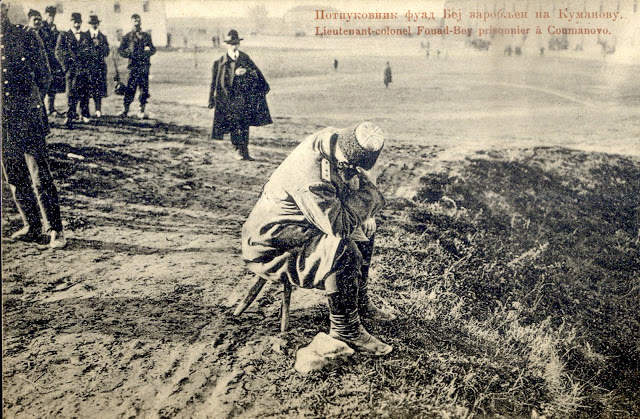

James Ker-Lindsay is essentially correct in pointing out that, for all the heady symbolism of centuries-long battles with the Ottomans, the modern conflict over Kosovo has its more immediate roots in the First Balkan War of 1912-13. (Ker-Lindsay 2009, 8) This war changed facts on the ground, rendering Albanian nationalists’ more moderate demands redundant, and the push for full independence an imperative. Among these facts was the fact that Albania was only finding its feet as a coherent polity, and did not have the means to defend all of the territory it aspired to. Neither did the Turks. A key moment in the region’s modern history comes at the Battle of Kumanovo (23–24 October 1912) in Kosovo vilayet (but now in Macedonia), where the Serbs defeated the Ottoman army and conquered the area, dividing it up between them and the Montenegrins at the subsequent London conference.

When the dust had settled (there was a second Balkan war only a few months later), an independent Albania had been established. This happened, not because the Albanians had been able to make good their ambitions through force of arms, but because Austria-Hungary and Italy wanted a means of weakening Serbia, and an Albanian state prevented them from obtaining coastal territory and becoming an Adriatic sea power. But the new Albanian state did not include Kosovo which, as the Serbs saw it, had just been redeemed from centuries of ‘foreign’ domination. Somewhat ironically though, just as the Serbs finally conquered Kosovo, Serbs were becoming a minority in the area.

But this didn’t matter to them.

By this stage, Kosovo had come to occupy such a central part of the Serbian national narrative that the wishes of the majority actually living there mattered less than historical claims to precendence, national honour, destiny… And lest we think the Serbs are somehow uniquely guilty of placing romantic nationalistic notions above self-determination and democracy, let’s not kid ourselves; as we speak, for example, the Spanish government routinely denies the rights of its national minorities to exercise the right to secede, no matter what the will of the majority in Catalonia and the Basque Country, and they are not alone.

In any case, the Serbs had plans to rectify the demographic imbalance, as they saw it. While they may have failed to convince international diplomats to give them territory reaching to the sea by trying to establish majority status for Serbs in large swathes of territory, the effort involved took an enormous toll of Kosovo’s Albanian population. At least 20,000 Kosovar Albanians—women, children, men, noncombatants as well as combatants—were massacred, and a rampage of torture and forced conversion to Orthodoxy (of Catholics as well as Muslims) caused perhaps 100,000 to flee the area, many settling in Bosnia. Although journalists and foreign visitors were kept out (always a bad sign) some were perceptive enough to discern the systematic and organised nature of this campaign. It was not just a few thugs and rapists let off the leash. Leon Trotsky, then reporting for a Ukrainian newspaper, wrote:

The Serbs, in their national endeavour to correct data in the ethnographical statistics that are not quite favourable to them, are engaged quite simply in systematic extermination of the Muslim population.

Many westerners, however, cheered this on, believing that the Serbs would ‘civilise’ the region. (Malcolm 1998, 253) In our own era (this was especially the case in the 1990s when I was growing up) Serbia has been depicted almost as a caricature baddie and blamed in the west for almost everything bad that happens in the Balkans. It is easy to forget that a hundred years ago, Serbia’s image among the western powers was one of a plucky underdog who had taken on the might of the evil Ottomans, and was now standing up to the sabre-rattling Austrians. Serbia was, after all, the ally of Britain, France and Russia in the First World War, and when the country was attacked in July 1914, they surprised the world by holding off the mighty Austrian army for more than a year. A great deal of sympathy was elicited for the Serbs as the Austrians waged a ruthless campaign of extermination and indiscriminate atrocities against civilians, including murder, rape and the destruction of crops, even poisoning wells to discourage Serbs from returning to their lands. Overrun in 1915 by Austro-Hungary, Kosovo was divided up between the latter and Bulgaria, and the Austrians were welcomed as liberators by the Albanians.

The tables turned on them, bands of Albanian rebels known as kaçaks (from the Turkish for ‘fugitive, outlaw, bandit) who had been waging armed resistance against the Serbs for the last few years, now assisted the Austrian troops in harrasing the Serb army as they fled across northern Albania, trying to reach the coast where the British and French navies were waiting to rescue them. Thousands perished of cold and hunger on the arduous journey over the mountains, and there are numerous accounts of Albanians, no doubt bitter at their recent suffering at the hands of the Serbs, either refusing to help or attacking them. This horrendous experience did wonders for the Serbs’ image in the British and French media, where money was collected for the ‘Serbian martyrs’ and St. Vitus’ day (see the last post for the significance of this to Serbs) was celebrated in Britain as ‘Kossovo Day’ in 1916.

Despite initial optimism that Austrian occupation would lead to the unification of Albania with Kosovo, this never happened, and things soon soured, especially in the Bulgarian-occupied parts of eastern Kosovo around Prizren and Pristina, where the Albanians were treated almost as bad as the Serbs and soon began waging their own war against their erstwhile ‘liberators’. By the end of the war, with allied-assistance, Serbia reconquered Kosovo and attempted to repopulate the area with Serbian colonists. As usual, revenge was exacted, refugees shifted around, many Albanians left. You can see this dip in the chart above, although some accounts suggest it may have been more dramatic than illustrated here. Židas Daskalovski claims, for example, that at least 300,000 Albanians were expelled from Kosovo between 1912 and 1941, while 14,000 Serbian families settled in the region, suggesting that the Albanian element was as high as 90% in 1912, down to 70% in 1941. (Bieber and Daskalovski, 2009, 17)

The brutality of the reconquest provoked, of course, its own resurgence of kaçak resistance, which reached its peak of intensity in the first half of the 1920s. This kept large areas of Kosovo ungovernable for years, and its leaders urged Albanians to refuse to pay taxes to the Yugoslav government and serve its armed forces. Among the most celebrated of these leaders was husband and wife Azem Bejta (killed 1924) and Shote Galica (killed 1927). Azem, interestingly, started his career fighting the Austrians, with the Serbs, but once the war was over focused on leading the revolt against rule from Belgrade, along with his wife, who dressed as a man in order to gain acceptance as a resistance leader in a male-dominated society. (Malcolm 1998, p.262)

Perhaps as devastating for the Kosovars’ cause, the kaçaks found an enemy in the rising power in Albanian politics, Ahmet Muhtar Zogolli, better known as ‘Zog’, who they briefly helped oust from power in 1924, but who returned and exerted a firmer and firmer grip over the country until declaring himself King Zog I in 1928. Having attempted to aid Zog’s enemies, assistance from their fellow Albanians across the border was less and less forthcoming for the Kosovars, as Zog—who had decided to focus on building bridges with Yugoslavia in the face of the main threat to Albania from Italy—established a focus on protecting and strengthening Albania within its existing borders. The idea of a ‘Greater Albania’ including Kosovo was more or less abandoned in Tirana, not just in his reign (he was head of state until World War II) but even afterwards under communist rule.

By the end of the 1920s, resistance to Serb (ahem, Yugoslav) rule had been thoroughly broken. In the following years, Albanian language and culture was all-but banned in public life; certainly those Albanian-language schools and journals that had been established under the Austrian occupation disappeared. There was an element of vindictiveness as well, given that the Serbs had no problem granting such rights to other minorities (Hungarians, Turks, Czechs, Germans) living within their borders. Much of this discrimination took place unofficially, and was denied by the Yugoslav authorities when confronted with foreign criticism, often arguing that there were no Albanians in Kosovo, merely Albanian-speaking Serbs. (Malcolm 1998, 268) While large parts of Europe were ratcheting up the anti-semitism against Jews, in Yugoslavia (where the Jewish population was relatively small and anti-semitism was less marked than other countries at that time) it was instead the Muslims, and specifically the Kosovar Albanians, who were turned on and victimised. (Benson 2014, 66-7)

All of this meant, of course, that when World War came knocking again, the Albanians of Kosovo were ready recruits for whoever happened to be fighting the Serbs. On the one hand, Italy invaded and occupied Albania (in all but name), dividing up Kosovo between themselves (more precisely the puppet government under an Italian king that they had installed in Tirana) while leaving Germany (who had occupied Yugoslavia) and Bulgaria to carve out their own occupation zones. Once again the scales tipped the other way, as Serbs were attacked and fled. 70,000 Serb refugees were registered in Belgrade in 1942. (Judah 2008, 47) In the period 1941-5 perhaps as many as 10,000 Serbs and Montenegrins were killed in Kosovo, but it should be noted that the corresponding figure for Albanians is even higher, around 12,000. (Malcolm 1998, p.312) The Kosovar Albanians’ position was complicated. Some fought with the Partisans against the Nazis and Serb-nationalist Chetniks (long story-look them up!) while others saw the Axis conquest of Yugoslavia as offering them an opportunity to realise their long-cherished dream of belonging in a Greater Albania.

Kosovo’s Albanians were particularly uninterested in the Allied cause because it was made fairly clear that the area would be handed back to the Yugoslavian state in the event that they won. It is unsurprising then, that some chosen to actively collaborate with the Nazis, and indeed the SS set up a Kosovo Albanian division, known as the SS Skanderbeg, which attracted around 6000 recruits, sent almost 300 Jews to the gas chambers and engaged in widespread looting, raping and pillaging of the Kosovan Serbs. They achieved little of note beyond this. Often when there is any mention of Nazi collaboration, I feel I should add a word of caution about reading too much, ideologically, into it. Because they are pretty much the exemplar of evil from the twentieth century, assistance or collaboration with the Nazis is often used to blacken the name of a nation or cause, even when this assistance was largely opportunistic, as opposed to reflecting any convergence of ideology. The most extreme examples of this are the ludicrous claims that the Palestinians somehow gave the idea for the Holocaust to Hitler. The fact that the Nazis found willing collaborators in some Muslim populations which had suffered at the hands of countries who happened to be fighting Germany in the war, has been exploited by some commentators to suggest that these peoples or their struggles were somehow fascistic in nature. There isn’t much evidence for this.

We have our own analogy of this in Ireland, where the IRA’s attempts (amateurish and almost comical as they were) to collaborate with the Abwehr (the Nazis’ intelligence agency) have been used by the enemies of Irish republicanism to suggest there was some ideology affinity between the two organisations. This is nonsense, and the IRA were at that time actually leaning towards the left, many of its members having chosen to fight with the International Brigades against the fascists in Spain. None of this is to excuse these groups’ collaboration with the Nazis, even when the horrors of the Holocaust were becoming known, merely to say that we should be wary of reading too much into the SS-recruited Handschar and Skanderbeg divisions of Bosnian and Kosovar Muslims during the war. The willingness of these groups to work with the Germans reflects more their animosity towards the common Serb enemy than any real sympathy with the Nazis’ politics which, let it be remembered, viewed Arabs and Slavic peoples as a lower form of life along with Jews (and basically everyone else who wasn’t from northern Europe). Let it also be remembered that large numbers of French, Poles, etc. collaborated willingly with the Nazi occupiers, not to mention the the 20,000 members of the British Union of Fascists or the 25,000 members of the German American Bund.

As the Partizans under Tito gradually won Yugoslavia back, many Albanians who had been fighting the Germans or Italians returned to fighting the Serbs. When Kosovo was ‘liberated’ in February 1945, martial law was declared and later that year, the area was formally annexed to Serbia as an ‘autonomous region’, following a request by the local (unelected) Regional People’s Council whose 142 members included only thirty-three Albanians. (Judah 2008, 49) The name of this new entity was changed to Kosovo and Metohija (Kosmet for short) Metohija being the name of the western part of the whole area, and a name favoured by Serbs, redolent of its history as an important centre of Serbian Orthodox monasticism. Many Communists, including Tito, were reportedly open in theory to the idea of Kosovo’s inclusion in a future enlarged Albanian, or some kind of Communist Balkan federation that encompassed the entire region, but that’s not how it played out.

Keeping Kosovo in Serbia as an autonomous region, and Vojvodina as an ‘autonomous province’ (a higher grade of autonomy than Kosovo but the differences in practice escape me) was, however, a convenient means of addressing what was seen by some as a structural flaw in the Yugoslav federal structure of six republics: namely, that SR Serbia was twice the size in population terms of the next-largest republic (Croatia) and contained around 40% of Yugoslavia’s total population, as well as being the location of the federal capital, Belgrade. All this was problematic to the vision touted by Tito and his people, of a federation of equals, so giving Vojvodina and Kosovo some measure of autonomy could be seen as a way of addressing this imbalance, albeit in a way that was, initially at least, largely symbolic. What autonomy the region did enjoy was limited to proposing a budget (that Belgrade would get approval of), directing its economic and cultural development. (Malcolm 1998, 316)

Relations between Enver Hoxha’s Communist Albania and Tito’s Yugoslavia were initially warm and the border between Kosovo and Albania was, until 1948, practically invisible on the ground. Then Tito had his falling out with Stalin, Hoxha took Stalin’s side, and the border was hermetically sealed. This period had nevertheless boosted the proportion of Albanians in the population, particularly as many Serbs whose lands had been taken during the war were initially prevented from returning by a decree from Tito. When they protested, he adjusted this to allow some to return under specific conditions, which provoked protests from the Albanians. In other words, it was all a bit of a mess and left a lot of bitterness, with both sides blaming the authorities for screwing things up. (Malcolm 1998, 317-8) In Tito’s Yugoslavia, both the Serbs and Albanians of Kosovo were thus regarded as politically dodgy, having both demonstrated their support for the Communists’ enemies during the war.

The region was ruled with correspondingly harshness. Aleksandar Ranković (below), minister of the interior and head of Yugoslavia’s security services in Kosovo from the end of the war until 1966, was a renowned hard man who pursued a policy of centralising power in Belgrade that foreshadowed the later policies of Slobodan Milošević. While at that time this involved suppressing any manifestation of nationalism by any of the peoples in the federation, in practice, the Albanians were more ruthlessly suppressed than others, it being strongly suspected that separatist sympathies were very strong under the surface of outward conformity with ‘brotherhood and unity’. Any kind of agitation for unity with Albania was, therefore, strictly forbidden, which is not to say that people didn’t keep wishing for it in secret.

Once again, Kosovo was subject to the buffeting of outside forces, which this time played in the Albanians’ favour. Firstly, Tito took a turn against the centralising impulses of men like Ranković in the 1960s. His fall from grace was accompanied by a loosening of strictures on Kosovo and an easing back of repression. Already, in 1963, Kosovo was upgraded to an ‘autonomous province’, giving it equal status with Vojvodina, although this conferred few, if any, tangible advantages. In fact, as Malcolm has noted, the constitution of that year gave the individual republics the right to form such autonomous provinces (even if none did) on their own initiative, and in a sense changed Kosovo from being a federal unit to a ‘mere function of the internal arrangements of the republic of Serbia’. (Malcolm 1998, 324) Another change in the weather came with Albania’s rapprochement with Yugoslavia which followed its falling out with the USSR under Khrushchev in 1961. Hoxha, always a big fanboy of Stalin, didn’t like the ‘Secret Speech‘ and accompanying disparagement of Stalin that followed. Hoxha’s regime was thus increasingly drawn back into Tito’s orbit. Yugoslavia in turn needed all the friends it could get against the Soviets, especially in the wake of the invasions of Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968). What better way to mend fences than to start treating the Albanians in Kosovo a bit better?

So the second half of the 1960s saw the beginning of a sort of renaissance for Kosovar Albanians. This was symbolised in several ways, firstly, by the dropping of the contentious Metohija part of the name in 1968. Secondly, amendments to the constitution gave Kosovo the right to their own flag and representation in all state organs, as well as the right to a seat on the rotating presidency of the republic. But too many symbols of improvement can also be a sign that things aren’t really changing all that much deep down, and for many Albanians, none of this was enough. That year saw violent protests calling for the upgrading of Kosovo to the status of republic. Why, it was asked, did 370,000 Montenegrins have their own republic but 1.2 million Albanians didn’t? The demand was flatly rejected by the Yugoslav top brass, because Albanians were regarded as a ‘nationality’ within Yugoslavia, not a ‘nation’. If you find this distinction confusing, join the club. As near as I can make out, the nations (Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Montenegrins and Macedonians, after 1971, Bosnian Muslims) were regarded as the nations that constituted Yugoslavia, whereas the Albanians and Hungarians in Vojvodina were minorities that had their own nation states outside the country.

So it went. The army was sent in to restore order, although the response was less authoritarian than in previous times (remember they were try to keep Enver Hoxha sweet) so some arrests and harassment, but also some more concessions: the establishment of the University of Pristina in 1969, where half the classes were to be taught in Albanian. In the following years, more substantive changes followed that went beyond a mere name change. 1974 saw yet another constitution, which gave Kosovo and Vojvodina practically all the legal rights of full republics, including its own assembly and constitution, full voting rights in the federal presidency, and an effective veto in a system that required unanimous decisions. This meant, of course, that Serbia’s power (now just one vote out of eight) was further diluted.

Although a demand for the status of republic in name eluded them, you might see this as the high watermark of what Kosovo Albanians achieved under the Yugoslav system. You might also, however, see it as the moment where the tide turns away from Serbs oppressing Albanians, to Serbs feeling they are the ones being oppressed. Whether they really were or not is debated. Certainly measures were put in place in the 1970s-80s to raise the economic and social prospects of Albanians generally. A kind of Yugoslavian version of affirmative action saw many administrative positions, both regional and federal, reserved for Albanians, (Bieber and Daskalovski, 2009, 31) while the local Communist party—once largely devoid of Albanians—was being taken over by them as the 1980s wore on. (Ramet 2002, 17) Likewise, the Albanian language which had once been largely banished from public life, was increasingly being used not just in education but public administration. All of this, combined with the sight of Albanian flags being flown openly (which would have been regarded as treason only a few years earlier) was creating a growing resentment and acrimony among Kosovan Serbs.

But whether Serbs were being actually oppressed is another question. We have to remember that much of this was the resentment of a previously-privileged group who were now having to contend with the Albanians as their equals, not inferiors. Heavily outnumbered, there is no doubt the Serbs felt threatened, but claims that they were being trod on seem reminiscent of the claims to victim status made by Ulster Unionists or white South Africans, i.e. that they were no longer able to lord it over their neighbours. Certainly the census results of 1981 confirmed Serb fears that they were being outbred, but it should be remembered that at the very time they claimed they were being marginalised and pushed out, Serbs and Montenegrins—who formed 15 per cent of the population—had 30 per cent of the jobs. (Malcolm 1998, 337)

In fact, the next great civil disturbance to hit Kosovo, in the Spring of 1981, was an uprising of Albanians once again demanding full republic status, although the protests, which went on for a month, seem to have started over social issues such as unemployment rather than an explicit planned campaign to push for the republic. The J-curve hypothesis of how revolutionary situations develop argues that populations become rebellious, not when at the rock bottom of oppression, but when a period of improvement in their conditions develops, raising expectations, following which this improvement either stalls or is perceived to not proceed fast enough. This seems to have been the mood among Kosovo Albanians in the early 1980s. Opinion is divided. Židas Daskalovski claims that ‘the secessionist tendencies of the Albanian population culminated in the so-called March riots’ (Bieber and Daskalovski, 2009, 14) but others, such as Tim Judah point out that the whole thing started as a protest over two-hour queues for meals at the university and spiraled out of control from there. (Judah 2008, 57-58) Here is some (fairly rare) footage of the protests. It starts peacefully enough. Then you can hear the police starting to get pissed off:

As the protests got out of control, the tanks were sent in to subdue the students, who were by now being characterised as ‘separatists’ by the authorities. Officially, 57 people were killed, but the real number likely ran into the hundreds. (Judah 2008, 58) In the wake of these events, repression intensified again, but it was a Yugoslav—not a Serb—repression. This is important to note. Up until 1989, Albanians remained in charge of most of the organs of regional government, and even though Albanian Kosovars were subject to heightened scrutiny and harrassment from the police and army, the feeling among Kosovan Serbs that they were being treated badly grew more and more acute. As the decade progressed, these claims developed from grumbling to open claims that the Serbs were being deliberately intimidated into leaving, murdered, women being raped, etc. This narrative took hold partly because it was increasingly tolerated by the authorities since the death of Tito. The Orthodox church played its part, as did cultural institutions, such as the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, which issued its infamous ‘Memoradum’ in 1986 claiming that the the Serbian population faced a ‘physical, political, legal, and cultural genocide’ in Kosovo.

There was little evidence for any such planned expulsion of the Serbs at this time. As Leslie Benson has noted, the decline in Serb population had been going on for some time, and can as easily be explained by industrialisation and the attractions of northern Serbia. (Benson 2014, 143) But since when did facts matter? Serbs were convinced that they were destined to be wiped out. There was also their (not unfounded) resentment at the anomalous constitutional situation from 1974 which gave Kosovo delegates in the Serbian assembly, technically giving Kosovans a say in matters related to Serbia ‘proper’ (that part of Serbia excluding its autonomous provinces) while denying Serbians from outside Kosovo a corresponding say in Kosovo. There was talk in the highest echelons of government that this would need to be addressed, and the President of Serbia, Ivan Stamboliç, had become acutely aware by 1987 that something needed to be done to address tensions in the province.

At the same time, Kosovo was known as a quagmire, an intractable problem where any improvement in the lot of Serbs would, by definition, be seen as a diminution in the status of Albanians, and vice versa. In other words, a graveyard of careers. Before succeeding to the presidency, Stamboliç had pulled strings so that his long-time friend and protégé, Slobodan Milošević, be made his successor as Chairman of the League of Communists of Serbia. Trying to avoid the career-suicide that engaging with Kosovo entailed, Stamboliç sent Milošević to Kosovo to try and mediate between the two sides in April 1987. Things did not, to say the least, play out the way Stamboliç might have expected. Milošević was expected to meet with the mostly-Albanian party functionaries, but Serb crowds confronted him and demanded he meet with them too to discuss their grievances.

To everyone’s surprise, Milošević agreed, and that Friday a hall filled to the rafters with Serbs was given free rein to air every sort of claim related to the alleged ‘genocide’ in progress against them. Merely meeting the Serbs was a radical-enough step for a Communist politician, but what happened next was unheard of. Although local Albanian officials tried to explain that the Serb claims were gross exaggerations or outright lies, Milošević instead openly sided with the Serbs. Fighting broke out on the streets between the police and Serb protestors (there is good evidence that this sequence of events was not as spontaneous as it appeared) and Milošević went outside to urge calm. The standard playbook was for a grey-suited apparatchik to urge obedience towards the authorities and repeat blandishments about brotherhood and unity. Instead, confronted by Serbian protesters complaining about being beaten by the police, Milošević responded on camera: ‘You will not be beaten again’.

When these scenes were broadcast on the national news later that evening, the effect was electric among Serbs, not just in Kosovo but all over Serbia. Stamboliç had seen Milošević as someone he could trust, but also as someone who might be sacrificed as a scapegoat for the inevitable failure to mediate in Kosovo. Spoiler alert: he was wrong on both counts.

FURTHER READING/LISTENING/WATCHING

Leslie Benson, Yugoslavia : a concise history (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Florian Bieber and Židas Daskalovski, Understanding the war in Kosovo (London: Routledge, 2009)

Alex Cruikshanks’ History of Yugoslavia podcast, especially episodes 22 and 26

Tim Judah, Kosovo : What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2008)

James Ker-Lindsay, Kosovo: The Path to Contested Statehood in the Balkans (IB Tauris: London, 2009)

John Lampe, Yugoslavia as history : twice there was a country (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Noel Malcolm, Kosovo : a short story (New York University Press, 1998)

Sabrina Ramet, Balkan babel : the disintegration of Yugoslavia from the death of Tito to the war for Kosovo (Boulder, Colorado : Westview Press, 2002)

Miranda Vickers, The Albanians : a Modern History (IB Tauris: London, 1995)

The Death of Yugoslavia (BBC documentary series first broadcast in 1995)

Featured image above: postcard from 1918 showing the main square of Mitrovica, Kosovo.