The ostensible purpose of this blog has always been to chronicle the growth and development of political and militant Islam in the last half century, and the 1990s saw the eruption of a series of wars across the world that appeared to many the first skirmishes in the kind of apocalyptic showdown between Islam and the west that fundamentalists in both camps believed was inevitable and seemed, to a greater or lesser extent, to welcome. It is for this reason that I devoted a great deal of attention to the Algerian Civil War of the 1990s in the last three posts, one of the most obvious theaters of this conflict. The Algerian conflict was often understood at the time, both domestically and internationally, as a conflict between secularism and fundamentalist Islam. The same could not be said of another war which dominated the headlines for much of the 1990s, that in the former Yugoslavia, and especially Bosnia. This is because the war there had many other facets beyond the conflict of Muslims versus Christians. The Croat-Serb antipathy was at least as vital a dynamic, not to mention the intra-Christian rivalry of Catholic against Orthodox, and Bosnia is where the ambitions of ‘Greater Serbia’ and ‘Greater Croatia’ clash (we’ll get to that).

The Bosnian war was, as often as not, represented in the western media at least as an ‘ethnic’ conflict, but this is not an entirely satisfying way of looking at it. Yes, the actors in it were trying to establish nation states within defensible borders along ethnic lives (this is the war that gave the sinister term ‘ethnic cleansing’ to the world) but in Bosnia in particular, such trite explanations come up against some challenging questions. What is an ethnicity? What is a Bosnian? Is it something to do with language? Most people from the region can communicate with each other without difficulty and the area is characterised more by a continuum of dialects than separate languages. Indeed, when Yugoslavia existed, the language they spoke was considered a single one, called Serbo-Croatian, which today are regarded as several distinct one. Is it racial (whatever that means)? Hardly, since the people living in Bosnia today (even more so in urban areas like Sarajevo) are the product of generations of intermarriage and intermingling of Muslims, Serbs, Croats etc.

Furthermore, the Bosnian Muslims are indigenous to this part of Europe. We are familiar with a minority of Muslims in many European countries, like Turks in Germany or Algerians in France. Relatively recent arrivals, in most cases their presence dates to the period immediately after World War Two, and in many cases far more recently. That isn’t the case here. Muslims in this part of the Balkans have been there for centuries. In no sense (although attempts have been made to claim this) are they ‘intruders’ or somehow ‘outsiders’ to the area any more than anyone else. While differing in religion, they are Slavs who converted to Islam with the coming of the Ottomans (Pinson, 1996), ethnically similar to their neighbours, speaking what is essentially the same language, as long-established in their territory as any other population in Europe.

What about religion? Bosnian cannot be simply considered synonymous with Muslim. There are, after all, the Bosnian Serbs, not to mention Bosnian Croats. While some commentators during the war may have clumsily conflated Bosnia with Muslim, there were plenty of people living there at the outset who considered themselves Bosnian, who weren’t Muslim. As we will see below, there have been times in its history when the authorities of the day have tried either to make Muslim identity the basis of a Bosnian nationality, or to ‘force’ the Bosnians to choose between defining themselves as Serb or Croat, but by the time Yugoslavia began to split up, it could not be said that any of these efforts had decisively emerged triumphant. None of these definitions, therefore, is completely satisfying, which suggests that things are complicated in Bosnia, and we should be wary of choosing one single paradigm in which to view the conflict there.

Then there is Kosovo, a mainly Albanian-speaking, mainly Muslim, country which, on the eve of the breakup, probably would have been a more likely candidate than Bosnia for the main theater of the war. Ethnic tensions had already flared up there between the Albanians and Serbs in the 1980s and Milosovic basically launched his career as a nationalist there. Conflict has raged even more recently in Kosovo and remains unresolved as the Kosovo state is widely recognised by the international community which its Serb neighbour continues to claim it as a part of its territory. The plan is to set things up the eve of war in the 1990s, do the same in Kosovo in the next post, and combine events in both countries in a third part.

So, we are going to look at Muslims and Islam in what used to be Yugoslavia, not forgetting that Albania is almost 60% Muslim and Macedonia contains a large minority (33%) as well, but that we will focus on them in another post, someday. I should say from the outset that these posts make no pretension to being an overall history of the Yugoslav wars, or even the Bosnian/Kosovo war, but will focus on the place of Islam and Muslims in the region and especially the tragic events of the 1990s. If it gives the impression that religion was the only issue at stake in these conflicts, or that jihadist fighters constituted the majority of combatants on the Bosnian side, that would be a false impression. No doubt choosing to focus on merely one aspect is open to that danger, but I will try and maintain a sense of proportion and context within the broader picture as best I can.

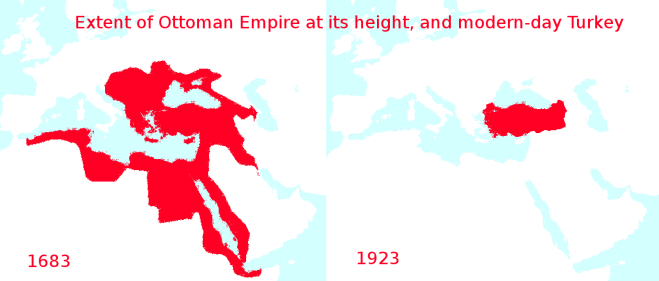

So how did Islam end up establishing this peripheral presence in Europe? The short answer is: the Ottoman Empire. This massive and powerful polity rose to domination in the eastern Mediterrannean in the 14th century, reached its zenith at the end of the seventeenth and went into a slow decline, finally collapsing in 1922, after it found itself on the wrong side in World War One, losing what remained of its empire and transforming itself into the modern state of Turkey within much-reduced borders. This collapse overshadows much of the introductory matter to individual countries’ histories on this blog, but as we’re concerned about a modern history of Muslim lands, we haven’t looked at it directly. No doubt when I do a post on Turkey we will go into it in a bit more detail.

For our purposes, 1389 is a key date. In this year the Battle of Kosovo saw the advancing Ottomans defeat armies of the disintegrating Serbian empire. It essentially established Ottoman hegemony in the region for the next half millennium, but there are several important caveats to note with respect to this. Firstly, the Ottoman’s suffered heavy casualties (as did the Serbs), including their Sultan, Murad I, who had led the army into battle personally. The extent of these losses have been linked to a slowing down of what had been a rapid expansion into southeastern Europe at the time, and in fact the line of Ottoman control it established would have important long-term consequences for the South Slavic peoples. While Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina came under Ottoman rule, Croatia and Slovenia remained outside their empire, left to domination by the Christian Habsburg rulers. This attribute of Yugoslavia (yes, I’m going to use the term anachronistically throughout this) as a borderland between two vast empires—Habsburg and Ottoman—both of which collapses at the end of World War One, will be of immense importance in shaping the region’s history.

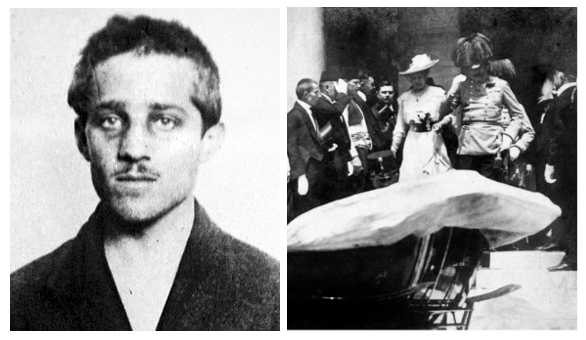

In modern times, perhaps as important as the fact and consequences of the battle has been its commemoration in the annals of Serb nationalism. Despite defeat, the heroic stand against the Ottomans, inflicting on them a Pyrrhic victory, became a source of pride and celebration for Serbs, and its date, St. Vitus’ day, became a key focus in the crystallisation of modern Serb identity. This is especially true since the late nineteenth century and for insights into this, I should credit Alex Cruikshanks and his excellent History of Yugoslavia podcast which I highly recommend. The date was somewhat insensitively (through sheer carelessness apparently), chosen for the visit of a certain Archduke Franz Ferdinand to visit Sarajevo in 1914, a fact which no doubt contributed to the determination of certain young men to shoot him.

I say the 1389 Battle of Kosovo is a key date mainly because it has loomed so large in the memory. In fact, most historians question the idea that it marked a decisive turning point in the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans, or slowed it down. It seems to have been one among many milestones, a major battle no doubt, but not the last stand it is sometimes presented. Ottoman control over the region was not in fact consolidated until after their epoch-making conquest of Constantinople in 1453, bringing to an end, in theory at least, an Eastern Roman Byzantine Empire which had survived for over a thousand years. In its wake, Bosnia was finally conquered in 1463 and the area to its southwest, Herzegovina, in 1483. Bosnia had long been a land on the border between empires. At one time a domain of the Byzantine Empire, it had been under the sway of Hungary for some time prior to Ottoman conquest. It was home to three competing forms of Christianity before the arrival of Islam: Roman Catholicism, Serb Orthodoxy, and a native form independent of both, the Bosnian church, often identified with the Bogomils, a neo-Gnostic sect, who were regarded as heretics by both the other sects.

It is this fragmentation that is often cited as the reason so many Bosnians converted so readily to Islam under Ottoman rule. Poorly organised and busy fighting each other, the Christian churches were ill prepared to meet the challenge of the Ottomans’ religion in an area where Christianity had never put down really deep roots. Another explanation is that members of the Bosnian church, long suffering under persecution from Rome, were happy to embrace Islam, although the importance of this has been disputed by some. (Pinson, 1996) Either way, it is worth repeating it: the presence of large numbers of Muslims in Bosnia was mainly the result of Slavic peoples native to the area converting to Islam, not colonists brought in by the Turks to replace the native population. This is not to say that mass conversions started immediately. There is little evidence these were forced on the population, and there was little overt suppression of Christianity by the Ottomans. The only church that is basically wiped out at this point is the Bosnian church, although that was as much a result of pressure from their fellow-Christians as it was from the Ottomans. Certainly, the new rulers created the conditions that made it advantageous to become a Muslim and this produced its results over time, but it did not happen overnight.

Indeed, the religious consequences for Bosnia of the Ottoman conquest were far more complicated than might first appear. While the Ottomans made it hard for Catholics to build churches, proselytise, etc. they were noticeably much more tolerant towards Orthodox members. While the Catholic church was a powerful and hostile entity with its centre in Rome (the Crusades weren’t ancient history at this time), the head of the Orthodox church lived under Ottoman control at their capital in Constantinople, and that community was seen as far less threatening. In this period, Orthodoxy in fact won converts from Catholics who feared oppression from their new rulers. Instead of a flood of Muslim migrants into Bosnia, if anything the striking migration is that of Orthodox Serbs, initially fleeing the Ottoman invasion of their own country into Bosnia, which partly explains the intermingling of Orthodox Serbs in the Bosnian population which will have important consequences down the line. Moreover, many of these Serbs settled on land bordering Croatia, from which Catholics had fled. A result of this was that some of the areas with the highest concentration of Bosnian Serbs in the 1990s were not necessarily along the border with Serbia but right next to Croatia. This should give us pause to think about the impossibility of redrawing borders along clean ethnic lines, simply rejigging things so that everyone gets to be part of the nation they feel they belong. In Bosnia this wasn’t possible. People were all mixed up. Hence the brutal logic of ‘ethnic cleansing’.

I have dwelt on these medieval origins of Islam in Bosnia, but we are never going to get to the 1990s if we don’t do a bit of serious fast-forwarding now. We are therefore going to gloss over the 15th to early 19th centuries, simply noting that these were far from uneventful, but that they were also a relatively stable period. Certainly Bosnia saw dramatic ethnic and economic changes, but the height of Ottoman power (its borders encompassed Hungary and reached the doorstep of Vienna in the late 17th century) saw a period of prosperity and development as the area became the core of Ottoman rule in southeastern Europe. Urban centres like Mostar and Sarajevo grew into major centers of trade, and Bosnian Muslims played a prominent role in Ottoman administration, the arts and sciences. Many have noted a correlation between urbanisation in Bosnia (a place that had hitherto had few towns, never mind cities) and Islamisation. The towns, especially Sarajevo, became Muslim in population, and there does seem some truth in the generalisation that the cities were Muslim and the countryside Christian, even down to the 1990s.

Over time, the nature of Bosnian society inevitably changed. At the height of Ottoman power, this had been a core imperial territory, far from the frontier, relatively secure, stable and confident. As its borders contracted and Bosnia once again became frontier territory, however, certain characteristics begin to emerge. The practice of Islam, for example, became noticeably more conservative in Bosnia than other parts of the Ottoman empire, often the case when a religious community finds itself situated in an outpost far from the centre, surrounded by other religions. This was partly a result of isolation, but also no doubt because the great wars of the 1680s-1690s, which saw the conquest by Christians of Ottoman possessions in Hungary, sent shitloads of Muslim refugees into Bosnia, bringing with them a lingering fear and hostility towards Christianity.

Being the closest part of the empire to the Austrian empire (the Ottomans’ greatest external enemy at the time) had its own effect. As frontier societies tend to, Bosnia became a more martial and militant place. The Janissaries, elite troops raised locally that the Ottomans would use to fight their wars in far-flung corners of their empire, became a hugely influential and powerful class in their own right. The Ottomans had a unique system of recruiting and utilising the talents of people from the countries it had conquered, and Bosnia was no exception. Those, like the Janissaries, prepared to convert in religion and conform to the new order were rewarded accordingly. Over time, a class of wealthy Muslim landowners emerged, would would resist attempts by the imperial government to encroach upon their privileges by, for example, raising taxes.

Bosnia was ruled with a light touch for a long time, but tensions became more and more apparent in the 19th century as the Ottoman state attempted to halt its decline, relative to the European powers, by reforming and modernising itself along more rational lines. The landowners and Jannissaries in Bosnia furiously resisted such reforms, and eventually rose up in arms in 1831. While they were defeated, this did not put an end to the deteriorating situation in Bosnia. Placed under greater and greater pressure from Constantinople, the local Muslim rulers took out their frustration on their Christian peasantry, increasing the tax burden to intolerable levels in an attempt to offset the financial impact on their resources. This precipitated an uprising in Herzegovina (map below) which then spread to other parts of Bosnia.

This uprising was taking place against the backdrop of what historians in English call the Great Eastern Crisis (1875–78), a major episode in the decline of Ottoman power in Europe, whereby Bulgaria attained independence and the already-independent principalities of Serbia and Montenegro sought to expand into lands inhabited by their compatriots. Bosnia meanwhile came under occupation by Austria-Hungary, who used the weakness of the Ottomans to exert control of the region, as much to prevent the Serbs from taking over as anything else. Bosnia was not formally annexed but simply occupied and administered by Austria-Hungary, but everyone knew the Ottomans (by now dubbed the ‘sick man of Europe’) were gone for good. The consent of Europe’s big powers was obtained for the occupation at the 1878 Congress of Berlin.

This does not mean the people who actually lived in Bosnia were content to see them walk in and take over without a fight. Their new rulers apparently thought this would be the case. Gyula Andrássy, the Foreign Minister of Austria-Hungary, remarked that the occupation would be a ‘walk with a brass band’. (Cruikshanks, 2018) The Ottomans and their local allies put up an unexpectedly stiff resistance, however, inflicting thousands of casualties on the invader. Nevertheless, by October 1878 Sarajevo was occupied and over four centuries of Ottoman rule at an end. At least de facto, because on paper Bosnia would remain an Ottoman possession until 1908, when Austria-Hungary formally annexed it. In the intervening decades, Bosnia was run by the Austro-Hungarian finance ministry (who ran military and foreign affairs), a compromise between the Austrians and Hungarians who, with the Compromise of 1867, had established a dual monarchy in which both Austria and Hungary were (in theory at least) equal partners. Most ministries were separate except finance and military, so to avoid either partner getting Bosnia, it was given to this common body.

Formal annexation in 1908 would aggravate Austria-Hungary’s relations with Russia and, above all, Serbia (by then an independent kingdom) which is pretty much the state of affairs as they stood when a young Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip (below left), a member of a secret society pledged to end Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia, shot dead the heir to the throne, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie (below right), in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. And the rest, as they say, is history.

The First World War represented a profound reshuffle of the cards in the Balkans. By its end, both the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires were broken and dismantled, resulting in the creation of about a dozen new, more or less independent states. Among these was the clumsily-titled Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, the culmination of the hopes and dreams of a movement which had emerged in the nineteenth century called Yugoslavism (from jugo ‘south’ and slavija ‘land of the Slavs’ i.e. land of the southern Slavs). This was an ideology that sought to unite the various ethnicities in the area in one strong unified state that could stand up for itself against its formidable external enemies. Some proponents saw their own nationality as natural leaders of the movement, others saw it as a means of uniting what they saw as their own people, be they Serbs, Croats or whoever, in one national territory, bypassing the awkward fact that these peoples did not always inhabit discrete geographically territories. It was an idealistic idea in many ways, more an aspiration towards a national Yugoslav identity than a manifestation of one that was already established.

At our vantage point in history, knowing what we know about Yugoslavia’s ultimate fate, it might seem hopelessly idealistic and doomed to fail from the start. We should remember, however, that many states we have come to regard today as natural expressions of a ‘nation’ or national identity, were really forged in the same way Yugoslavia attempted to create a Yugoslav people, a somewhat artificial moulding and melding of disparate regional identities, people speaking ‘dialects’ which bordered on being mutually-unintelligible languages, different values, religions, moulded by the power of the nineteenth-century state and rationalised education systems into more homogenous ‘nations’. Such was the case with a country like France, which we think of as a naturally-coherent entity but, as a writer like Eugene Weber has shown, was sewn together from a variety of regional identities and peoples who could hardly be described as French until they were taught to be French by a systematising, centralising modern state.

Even more similar to Yugoslavia are places like Germany and Italy, which didn’t achieve political unity until well into the nineteenth century and were constructed from a hodgepodge of disparate statelets. The idea of a South Slav nation was no more idealistic than these cases really. The fact that Yugoslavia was ultimately less successful makes it appear more untenable. Cruikshanks has also noted that, just as in the case of Germany and Italy, where the unification effort was led by Prussia and Piedmont respectively, some Serbs saw themselves as the South Slav equivalent, destined to lead ‘their’ peoples to freedom under their auspices. Indeed the magazine of the Serbian Black Hand group, which facilitated Princip’s assassination of the Archduke, was called ‘Piedmont’. This offers a hint that Yugoslavism was not always entirely altruistic, tolerant and all-embracing. Nationalism among the South Slav peoples, especially the Serbs and Croats, has never been a monolithic thing. There were shades of opinion, everything from enlightened cosmopolitans who wanted to create a political framework that might accommodate the shades of identity that characterise the region, to those (again, usually Serbs or Croats) who saw it as a means of creating a state which might facilitate their domination over their neighbours and enable them to rule areas in which ‘their’ people were in a statistical minority.

In 1918, the newly-founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes included Bosnia, but not its name, which tells you something about the position of Bosnia’s Muslims in the new country. While the peoples mentioned in the kingdom’s title were recognised, ‘Bosnians’ were not. In a very real sense, Bosnian Muslims were expected to choose being Serb or Croat by nationality, their religion being immaterial. There were certainly no shortage of Serb nationalists who regarded Bosnian Muslims as nothing more than ‘unredeemed’ ‘Serbs who had yet to be drawn into the national fold’. (Pinson, 1996) And this will often be the problem with centralising impulses in Yugoslavia, that they will often be seen (with some justification it must be said) as efforts to strengthen one group at the expense of the others. The reforms that accompanied the changing of the country’s name to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, for example, included the re-division of the entire kingdom into nine banovinas or regions, which were named after the main rivers and, in theory, gave no cognisance to national and ethnic boundaries. Whether they really did, however, is debatable. Croats and Muslims, for example, could hardly fail to notice that the re-division split up their own territories, while leaving Serbs in a majority in six of the new units. A centralising drive, ostensibly to strengthen the federal authority but widely suspected as a means of exerting Serb authority, will once again play a role in the lead up to war in 1991.

Before we get there, I want to backtrack a bit and look at the development of a Bosnian identity, and what that consisted of. I mentioned that, fearing an end to the privileges they had enjoyed under Ottoman rule, Bosnia’s Muslims resisted Austrian occupation. In the decades that followed the occupation, however, their position did not deteriorate as dramatically as might be expected. There were several reasons for this. The Austrians, having encountered initial resistance, were solicitous not to provoke any more. They allowed Muslims a certain degree of freedom to assert their religious identity and attempted, with some success, to co-opt the wealthy elite and religious leadership of the community, creating their own institutions and appointing their own Habsburg-friendly clerics to prominent positions. These were not universally accepted by the faithful, but definitely succeeded in taking the edge of their animosity. There was also a fairly steady and significant stream of Muslim emigration to Turkey in these years, indicating that not all were happy to stay and accept rule by Christians.

Perhaps one of the most important developments was the attempt by the Habsburg authorities to promote a Bosniak national identity. They did this partly to wean the Muslims away from loyalty to the Ottomans, and to blunt the idea of a Yugoslav identity that might encourage the Serbs and Croats attachment to their neighbouring compatriots. The idea was that all Bosnians would be encouraged to feel Bosnian, not Serb, Croat or Muslim, but most people didn’t buy it, certainly not the first two. In fact, these efforts may ironically have sharpened feelings of identification with the Croat or Serb nation among Catholic and Orthodox Bosnians. After all, until well into the nineteenth century (and this is true across large swathes of Europe) the imperative to feel part of any nation was hardly very acute among people, especially in rural areas where many never traveled more than a few kilometres from home in their entire life. Most people were probably happy enough to identify with their local village or region and leave it at that. It was only when some civil servant came along and told you you had to feel Bosnian that you suddenly felt you might be a Serb.

The only group among whom the Austrians’ tactic had something of the desired effect was Bosnia’s Muslims. It is in these decades that the first stirrings of a separate ‘Bosnian Muslim’ nationality become detectable, of a people who are beginning to perceive themselves as separate from their Ottoman overlord. Perhaps there is some symbolism in the fact that when the Austrians marched in in 1878, the Ottoman vizier sent a message to the locals to remain calm, because the empire was in no position to assist them. The local committee in Sarajevo responded with a message to the Ottomans: don’t send any more advice. (Pinson, 1996)

If the Austrians failed to make everyone feel Bosnian, the division of Bosnia into three ethnic groups nevertheless served some of their purposes just as well, keeping the different communities divided and at each other’s throats so they couldn’t unite in opposition to their rule. During World War One, for example, when the Serbs were public enemy number one, the Austrians organised militia of Croats and Muslims, known as Schützkorps, to kill Serbs. When the war ended, as we have seen, Bosnia’s Muslims were compelled to live in a state that didn’t recognise their existence as a separate people. It was in this atmosphere that the Yugoslav Muslim Organization (JMO) was founded in 1919. This has been described by Leslie Benson describes as ‘the voice of a frightened people’, and that’s an apt description. The JMO’s main goal through most of its two-decade existence was to hold its own and see to it that Bosnia wasn’t simply swallowed up in a Serb and Croat-dominated Yugoslavia. A significant feature of their strategy was to move away from religion as a marker of Bosnian identity and to abandon much of the conservative, explicitly Islamic features that had characterised previous Muslim political organisations.

Sometimes allied with Serbs, sometimes against them, the JMO became the dominant political party within Bosnia in the inter-war period, its leaders drawn from the ranks of the professional middle classes of the cities, rather than the religious establishment. These laid the foundations for a Bosnian Muslim identity that would be ethnic rather than religious in nature. In a post-Ottoman context, this is not as strange as it may sound. The Ottoman ‘millet’ system had divided subject populations up according to religious denomination, granting substantial autonomy in limited judicial and religious areas to the various groups. As a result, religion became more of a marker of identity than language, race or occupation for example. (Lopasic, 1981) It was, the idea went, the Muslims’ shared historical experience and culture that defined them. While this may have been religious in origin, it had developed into something broader than that, and that something had become a nationality, as distinct as any other in the multi-ethnic kingdom. As we have already seen, not everyone in Yugoslavia accepted the logic of this, but the JMO was successful and influential enough to get themselves banned in the 1930s, and after the Second World War, when the kingdom became the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia under Communist rule, the idea of Bosnian Muslims as one of the country’s nationalities will slowly gain traction.

Initially the Communists were ambiguous about recognising the Muslims in Bosnia as a constituent nationality, instead simply defining them as a community with equal rights to Serbs and Croats. Being communists, overt religious activity was discouraged in public life. Tito’s regime got into all sorts of conflicts with the Catholic church and as for Muslims, Sufi orders were banned and mosques closed. In the 1960s, however, strictures began to loosen. This may be partly due to Yugoslavia’s relatively liberal (by eastern bloc standards) regime, but it must also be seen in the context of federal politics. From around 1966, Tito was more dependant on Bosnian party members in his struggle with deviationist trends in the Serb and Croat branches. By now, the original idea of a secular, socialist Bosnian Muslim identity had put down roots, and had become the dominant community within the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Seeking their support, Tito supported the establishment of an ethnic category of ‘Muslim’ first in the census of 1961 and later in the new constitution, promulgated in 1968. To stress once again, this identity had by now become something almost denuded of religion. This has been well illustrated by Ivo Banac, who notes that a Bosnian could be a Muslim by nationality and Jehovah’s Witness by religion, like many of the inhabitants of the town of Zavidovići.

It’s worth pausing here to consider the political context. While I don’t want to dwell in too much detail on the country’s deepening crisis, it’s impossible to consider what happened in Bosnia without understanding the various dynamics at play in the last decades of Yugoslavia’s existence. The simplest way of understanding the situation is to do a quick synopsis of Yugoslavia’s post-war history under Tito. Central to everything that followed is that Yugoslavia, while run by a Communist party, was not a satellite of the Soviet Union following its expulsion from the Cominform in 1948. The reasons for Tito’s falling out with Stalin are complex, but the short version is: Stalin didn’t like the Yugoslav leader’s independent foreign policy (provocative action towards the western powers, support for the Greek left in that country’s civil war) in a period when he was trying to keep the Cold War as cold as possible. Tito refused to toe the line and obey Moscow’s orders and so the rift opened. Seeking new allies, Yugoslavia took a leading role (along with Nehru’s India and Nasser’s Egypt) in the Non-Aligned Movement, and reached an amicable understanding with the United States and its western allies, by which trade, tourism and diplomatic relations were developed in return for which Yugoslavia would demonstrate to other countries the advantages of independence from Moscow. The tacit agreement was that, if the west agreed not to interfere in how Yugoslavia was run or expect military co-operation, Tito was happy to see his country integrated economically into the western bloc, in so far as that was possible for an ostensibly communist country to become integrated into a capitalist world economy.

I say ‘ostensibly’ because, as Yugoslavia slipped from the grasp of Soviet control it developed its own brand of communism, characterised by a greater degree of pluralism and decentralisation than was typical of the average Warsaw Pact country. This does not mean that Tito allowed multi-party elections or complete freedom of expression, but it does mean a certain amount of involvement for ordinary people in choosing representatives to communal government and workers’ councils. While relationships with the eastern bloc were subject to diplomatic instability (some improvement of relations followed the death of Stalin in 1953, but the USSR’s intervention in Hungary in 1956 once again soured things) by the early 1960s, Tito’s government was liberalising the economy by reducing state control over wages and giving individual enterprises greater control over the management of their own affairs. At the same time huge loans were taken from western governments, while the country signed the GATT (a precursor to the World Trade Organisation).

The ‘market socialism’ which developed in Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1970s was a weird hybrid. While some aspects were liberalised, others were not; the government retained price controls for example. At the same time, reforms were hindered by the problems they exacerbated: growing inequality and the development of a managerial elite (resented by the communist old guard) who rewarded themselves lavishly while the workers, who in theory were supposed to be able to exert influence over decision making so that their wages would not fall behind, were not able to, instead being subject to pay cuts and more demanding targets. Unemployment doubled in the four years between 1966 and 1970 from 6% to 12% while more than a million Yugoslavs emigrated, the majority working in West Germany. At the same time, much of the extra capital that reforms was supposed to generate did not materialise or was used up in paying managers’ and bureaucrats’ inflated salaries.

Inequality was not only a problem among individuals but among different regions of the federation, something that will have long-term consequences. By 1967, for example, Kosovo’s per capita income was less than a quarter of Slovenia’s (Lampe, 2010), and unemployment far lower there and in neighbouring Croatia than in the other regions. While the intention of reforms had been to knit together the country more closely, using increased production to generate profits that might be invested in underdeveloped regions, if anything it had the opposite effect, increasing the economic isolation of the individual republics so that, by the end of the 1970s, two-thirds of all goods and services were being exchanged within republics, and only 4 per cent of investment resources were jointly owned by firms cooperating across republican boundaries. (Benson, 2014)

Yugoslavia’s market reforms were, of course, long portrayed in the western media as an untrammelled success, but the people actually living through them often begged to differ. The strikes and student protests of 1968 had their counterpart here, where left-wing students protested for increased democracy in workplaces and universities along traditional Marxist lines. Tito, opportunistic as ever, came out publicly in support of the protesters and used them to buttress his power against rivals in his own party. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, which Yugoslavia vigorously criticised, was also used to rally the population around the leadership and win plaudits in the west. Tito’s actions in this period are a classic example of his cunning in manipulating the various players to consolidate his own power and keep the lid on Yugoslavia’s inherent tensions. He used the opportunity to open the party to a new generation of young enthusiasts, replacing many of his own rivals. He also introduced a series of amendments to the constitution in that year which strengthened the power of the individual republics at the expense of the federal organs.

Any attempt at decentralisation was viewed as a move against the Serbs of course, especially when the reforms included shaving off two parts of the Serbian SR which became ‘autonomous provinces’, but more of that later. Others, especially the Croats, were displeased that the reforms didn’t go far enough, and in 1971 the so-called ‘Croatian Spring’ saw a movement within the Communist party calling for initially fairly-modest measures towards decentralisation infiltrated by those (criticised as nationalists by the government) calling for greater recognition of Croatian language and culture as well as political autonomy. Realising the reforms had gone beyond his control, Tito clamped down with a good old-fashioned purge, imprisoning those he considered a threat and putting a lid on further liberalisation and decentralisation. Indeed, some reforms were now rolled back and control of certain functions by the federal government tightened, for example, control of foreign reserves and rights to trade with the outside world, not to mention the strengthening of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) which Croats and other nationalities saw as unduly dominated by Serbs.

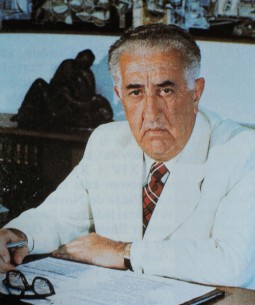

Essentially this period witnessed a complex mishmash of reforms and counter-reforms that pleased no-one entirely and ended up alienating more or less everyone. It goes some of the way towards explaining why Tito leaned on the support of Bosnian Muslims, as he identified the sources of his trouble as being primarily in Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana. He promoted men like Džemal Bijedić (above), a Bosnian Muslim who was Prime Minister of Yugoslavia from 1971 until 1977, when he was killed in a plane crash which some have speculated was engineered by Serbian rivals. Bijedić was often touted as a possible successor in the event of Tito’s death, and was widely lauded for his successful development of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s economic, transport and educational infrastructure. He was also active in promoting the equality of a Muslim nationality with the countries’ other identities, and he oversaw a renaissance of Muslim culture in Bosnia: not necessarily religious in character, but a growing confidence and pride in Bosnian Muslim heritage and their history as a discrete experience, not just some awkward middle ground between Serbs and Croats. This of course, was to provoke unease and hostility among the latter peoples who also lived in Bosnia.

Just as Croatia had seen activists and writers become increasingly vociferous about wishing to preserve and assert their distinctive culture instead of having it assimilated into a generic Yugoslav culture, so too in Bosnia voices began to grow more confident in asserting the rights of Muslims, not only on a cultural and political, but even on a religious plane. One of the most prominent of these was a lawyer named Alija Izetbegović, who had been imprisoned by the authorities at the end of World War II for his membership of the ‘Young Muslims’, a sort of Bosnian equivalent of the Muslim Brotherhood. After his release, Izetbegović had kept his head down for most of the 1950s and 1960s, but at the end of the latter decade published a book entitled The Islamic Declaration, which at the time was a largely theoretical work on the place of Islam and its relationship to the modern state. It has since become the source of much controversy, none of which I feel qualified to resolve.

Some (his enemies) have read it as a call to establish an Islamic state, in disregard of Bosnia’s Orthodox or Catholic peoples. Certainly it contains material that seems to suggest a revival of Islam, the taking of power by Muslims under certain (on this there is ambiguity) circumstances, and the imposition of Islamic law on the state. Others have argued, however, that Izetbegović should be judged by his subsequent political writings and actions, which indicate he held no such ambitions. As we will see, when he became the first president of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992, he seems to have been far more keen on creating a multi-ethnic nation state within secure borders than anything else, and religion appears to have receded from the public to a more private realm. To the Communist authorities in 1983, however, his work, and that of other Muslim intellectuals, was seen as deeply subversive and counter-revolutionary. They were put on trial and he was sentenced to fourteen years imprisonment, a sentence that was considered excessive even at the time. This was later commuted, only two years being actually served

We should, however, not exaggerate the level of ‘ethnic’ tension between Bosnian Muslims and their Serb/Croat neighbours at this stage. In the 1980s, things must have appeared relatively harmonious in Bosnia compared to Kosovo, where ethnic conflict had already come out into the open at the beginning and the end of the decade. If anything, it was other forces that were driving the country off a cliff. While obvious in retrospect, at the time they were less so. Sarajevo, after all, hosted a Winter Olympics in 1984, hardly symptomatic of a country collapsing in on itself! Several factors worsened matters, however. Firstly, the old man died in May 1980. By the sheer force of his charisma and reputation, he had kept in check many of the disparate ambitions at work in Yugoslav politics. After he was gone, there was no-one with the stature to stop reform initiatives from running out of control, as they inevitably did.

Secondly, with all of these other tensions bubbling over, the economy took a further nose dive in the 1980s. My own impression is that it was the economy more than anything else that incubated unrest. If you can keep a people well fed and supplied with copious consumer goods, the majority tend to take less risks in pursuit of civil rights and other, less material political objectives. If you don’t, they tend to start gravitating towards causes that provide a focus for their disenchantment. The discontent that resulted took shape in ideological forms. In Yugoslavia, it was predominantly nationalism rather than religious fundamentalism, but how many times in this blog have we seen this pattern? Relative prosperity and optimism up to the 1970s, economic decline, social instability opening a door to the rise of extremism.

During the 1970s, reckless government borrowing and spending masked the underlying problems and promoted a veneer of prosperity, especially when (as was often the case) Yugoslavia was favourably compared to countries like Romania or Bulgaria. Some white-collar workers and bureaucrats enjoyed conspicuous ownership of cars and kitchen appliances, holidays abroad, all of which garnered the attention of those in the west who were eager to equate economic liberalism with success. The reality is that these lucky ones were a small minority and they were in any case living beyond their means. The country was in fact running a huge trade deficit, its weaknesses mitigated somewhat by income from tourism and remittances sent home by Yugoslavs abroad. This left the ‘socialist’ republic hopelessly in hock to, and dependent on, capitalism, and it was only a matter of time before these chickens came home to roost.

They began to as the surrounding geopolitical situation changed with the decline of the Soviet Union and collapse of its sphere of influence in eastern Europe. When the Cold War was at its height, Tito had always been able to take economic advantage of the Americans’ eagerness to keep Yugoslavia on their side. Under those circumstances, the west could be relied on to subsidise whatever economic difficulties the country happened to find itself in. As things began to thaw with the advent of Gorbachev, glasnost and perestroika, however, improving relations between east and west reduced Yugoslavia’s strategic importance. A sense of crisis slowly enveloped the ruling elite, but different factions interpreted this crisis differently, and the measures that needed to be taken to tackle it. Many among this elite came to the conclusion that these would necessitate a rolling back of much of the decentralisation which had taken place since the 1960s. If international financiers were to be reassured that Yugoslavia was capable of implementing the fiscal and monetary strictures needed to secure loans, it was argued, the federation once again needed to be brought under tighter control from Belgrade. As we have already seen, however, in Yugoslavia, one person’s idea of ‘centralisation’ was another’s ‘domination’, and as we will see once we have looked at Kosovo in the next post, these efforts at centralisation will themselves be seen as—and provoke—a recrudescence of nationalism among the South Slavs.

FURTHER READING/LISTENING/WATCHING

Leslie Benson, Yugoslavia : a concise history (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Alex Cruikshanks’ History of Yugoslavia podcast, especially episodes 22 and 26

John Lampe, Yugoslavia as history : twice there was a country (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Alexander Lopasic, ‘Bosnian Muslims: A Search for Identity’ in Bulletin (British Society for Middle Eastern Studies), Vol. 8, No. 2 (1981), pp. 115-125.

Mark Pinson (ed.), The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina : their historic development from the Middle Ages to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, (Harvard University Press, 1996)

The Death of Yugoslavia (BBC documentary series first broadcast in 1995)

Featured image above: Detail from a cartoon from the Le Petit Journal showing the Austrian emperor, Franz Joseph, tearing Bosnia-Herzegovina away from the Ottoman Sultan, Abdul Hamid II.

[…] A contemporary history of the Muslim world, part 19: Bosnia #1 […]

LikeLike

[…] A contemporary history of the Muslim world, part 19: Bosnia #1 […]

LikeLike

[…] A contemporary history of the Muslim world, part 19: Bosnia #1 […]

LikeLike