Picking up where we left off in the post before last, in April 1987 the President of Serbia, Ivan Stamboliç, sent a party functionary, Slobodan Milošević, to Kosovo in an attempt to try and ease tensions building up in the province between ethnic Albanians and Serbs. The latter claimed (and their claims were believed by many in Serbia) that they were being systematically driven out and oppressed by the Albanians in the autonomous province. Milošević instead took the Serbs side in the conflict and his conduct on the visit was widely reported in the Belgrade media, turning him almost overnight into an enormously popular figure among ethnic Serbs throughout Yugoslavia (and these were many in number outside the borders of Serbia itself, not only in Kosovo, but also in Bosnia and Croatia).

While playing up to and exploiting such fears had been a strict no-no under Tito, as Communism began to falter and collapse around Europe towards the end of the 1980s, playing the nationalist card suddenly became possible, and figures emerged who were willing to do so to further their political career. The month’s that followed Milošević’s shenanigans in Kosovo saw serious maneuvering backstage by him and his allies to remove rivals for power. Stamboliç and his allies were forced to resign under accusations of being ‘soft’ on Albanian radicals and abusing their power. This paved the way for Milošević to become President of Serbia and embark on what he called his ‘Anti-bureaucratic revolution’, which essentially meant him and his cronies organising what appeared to be a spontaneous series of street protests (which often descended into violence) of Serbs, who were often shipped in from Kosovo. These were staged in various parts of Yugoslavia, effectively forcing the collapse of regional governments in Vojvodina and Montenegro and their replacement with compliant Milošević allies. These (along with Kosovo, which we’ll get to in a minute) created a solid ‘Serbian bloc’ in the state presidency which could at the very least block any motions made by Serbia’s opponents and (depending on Macedonia which often sided with the Serbs, fearing their own significant Albanian minority) could often outvote the others (Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia).

It was denied by the Serbs (yes, not all Serbs supported Milošević it should be remembered) that this ‘revolution’ was driven by nationalism, but everyone knew it was. There was another aspect to this drive towards ‘centralisation’ however, which I have mentioned in a previous post, and this was Milošević’s eagerness to implement free-market reforms in order to get his hands on IMF loans to bail the country out. A part of this was showing potential lenders that the central government had a firm grip on Yugoslavia as a whole, something which had been far from self-evident in the highly decentralised system that emerged in the 1970s.

Exerting control over the governments of Vojvodina and Montenegro had been straightforward enough for Milošević. Kosovo was a different story. Here, where Albanians heavily outnumbered the Serbs, they had more or less taken over the local Communist party. In addition to this, while Milošević could always mobilise Serbian mobs in other places where the rest of the population were hardly likely to get out on the streets to support moribund communist apparatchicks, in Kosovo, the Albanian politicians had their own foot soldiers prepared to fight to prevent a re-imposition of Serbian dominance. One of the most important of these groups were the miners in Trepça, a huge mine just north of Mitrovica which constituted one of Yugoslavia’s biggest enterprises. Miners in the communist world enjoyed a special position of moral authority and were not easily ignored, due to their ability to cripple a country by going on strike.

The initial salvo came with moves to revise the constitution in 1988, which provoked protest from Albanian leaders. When Milošević moved to remove those who stood in his way, the miners of Trepça went out on strike. Their man, Azem Vlassi (above left), was returned to power as head of the local Communist Party. Further pressure was exerted, however, and in May Vlassi was demoted and replaced by Kaqusha Jashari (above right) who, while not an ally of Miloseviç, was expected to be easier to intimidate. She wasn’t. By now it was becoming obvious that the extinction of Kosovo’s autonomy and full integration back into Serbia was the aim of Milošević and his people. Jashari publicly opposed the draft constitution that was published in June and pointed out that, despite all their rhetoric about preserving the integrity of Yugoslavia, it was Milošević and his campaign that was driven by nationalism and threatened the status quo. She too was removed in November 1988. In defense of their leaders, the miners of Trepça led a huge march to Pristina (500,000 are reported to have attended) carrying pictures of Tito to demonstrate their loyalty to the status quo and not (as their enemies alleged) their commitment to separatism. Within months, the miners’ protests had escalated into hunger strikes.

It was all to no avail. In February 1989, Milošević got the State Council and the Yugoslav president to grant him special powers in Kosovo. It should be pointed out that this decision took place as Belgrade was filling up with Milošević supporters, some of them Kosovan Serbs brought in for the occasion, others riled up by a pro-Milošević TV channel that got them out on the streets and surrounding the building in which the decisions were being made. Those hesitating about handing over power in Kosovo to Milošević were reportedly afraid they would never be allowed to leave the building alive if they didn’t.

The next day, Yugoslav army tanks rolled into Kosovo, Vlassi was arrested and imprisoned and protests met with relentless repression. The members of the provincial parliament were intimidated by Serbian police into voting yes to amendments to the constitution which nullified Kosovo’s autonomy. For a while, the pretense of being half-conciliatory towards the Albanians was kept up, but the indiscriminate beating (and worse) of Albanians by the police and army spiraled out of control. Even the local official pushed to the fore by Milošević’s campaign showed unease at the speed with which Kosovo was being transformed into a subordinate of Serbia. Tomislav Sekulić, a local Serb who counseled restraint by the security services, was shunted aside for his moderation. Rrahman Morina, widely seen as a pro-Serb Albanian police chief with a history of leading repression against his own people, had been appointed as local party head in early 1989 but wound up dead under suspicious circumstances the following year. By then the Serbs had done away with the pretense of treating Kosovo as an equal and had appointed (June 1990) a kind of governor. The following month, the provincial assembly was closed down and the building sealed off. A new Serbian constitution formally ended any last vestiges of autonomy. Albanians were systematically dismissed from public sector jobs and Albanian-language education put to an end. Albanian street names in Pristina were changed to Serb ones in 1992.

By this stage, of course, things were kicking off in the rest of Yugoslavia, as Slovenia and Croatia declared independence in June 1991, with Bosnia’s descent into war the following year. As the world’s attention gets diverted, there is often the impression that Kosovo goes ‘quiet’ at this point. To outward appearances, it does. All resistance and overt protest towards the Serb takeover was crushed, but something else happened in this period in Kosovo which, in a way, I find the most interesting part of the story. It made few headlines and even the Serbs took their eye off the situation, busy as they were elsewhere and thinking they had cowed the Albanians into submission for good. Increasingly marginalised and excluded from public life in Serbian-run Kosovo, the Albanians responded to their oppression by ignoring many of Serbia’s institutions and creating an underground, parallel civic society of their own.

Central to this development was the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK) and its leader Ibrahim Rugova (below). The League had been founded at the time Kosovo was having its autonomy stripped away in 1989. It was a broad church, encompassing Kosova Albanians from across the political spectrum, who were all broadly agreed two things: firstly, the necessity of resisting Serbian domination and secondly, that their only hope of doing this (given the completely dominant position of the Yugoslav army and police) was by non-violent means. Unlike other groups in Yugoslavia (the Croats for example), the Kosovars had no means of arming themselves, and knew that if it came to a fight, the Serbs would likely use the opportunity to either wipe them all out or expel them. Events such as Srebrenica would prove such fears well grounded. On the 21 September 1991, therefore, the Albanians under Rugova declared independence as the Republic of Kosova, soon to be ratified by 99% of those who participated in a referendum, organised in defiance of the Serbian authorities, who deemed it illegal.

From here on, then, two parallel administrations existed, both claiming sovereignty over the territory, the aforementioned Albanian-run republic, and the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija within Serbia. The Kosovar Albanians organised elections to their own parallel institutions in May 1992 and began to organise the infrastructure of a state: education, basic social services, the administration of justice, simply ignoring the Serbian state apparatus in their land. There was no shortage of teachers, administrators, etc. given the fact that many Albanians had been dismissed from their jobs in the Serb takeover, or asked to sign ‘loyalty oaths’ which was impossible for them to do without being ostracised from their own community. These people slotted neatly into the new underground state run by Rugova and the LDK.

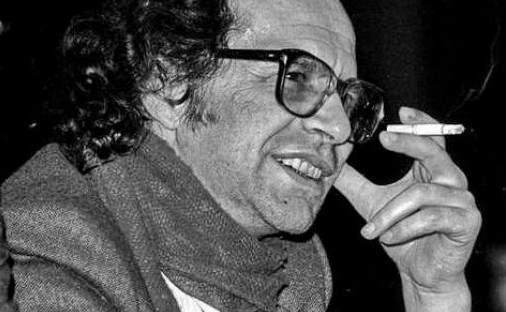

Rugova himself would come to be seen as the father of the nation by Kosovar Albanians, but he was an odd fit for this role in many ways. He had studied in Paris under the avant-garde philosopher and literary theorist, Roland Barthes, and became a professor of literature back in Kosovo, later head of the writers’ union. He was appointed leader of the LDK after another prominent figure refused the role, and to prevent someone else who no-one liked from getting it. He was (according to Tim Judah) ‘extraordinarily boring to talk to’ (Judah 2008, 72) and appears to have possessed little of the charm and personal magnetism normally associated with leaders of nascent nations. Nonetheless, he steered his people through these dangerous years with sagacity and caution, arguing that armed insurrection against the Serbs was hopeless and that passive resistance was the way to go.

All of this took place with little or no interference from the Serb authorities which, given their brutality elsewhere in Yugoslavia, seems strange at first glance. On closer reflection, however, it made sense from a Serbian perspective to let the Kosovars get on with it, so long as they kept their resistance passive. For starters, Serb forces were busy enough fighting in Croatia and Bosnia in these years. But there was also a complex realpolitik at play here, a weird (if temporary) modus vivendi between the Albanians and Serbs. In the 1992 Yugoslav elections, for example, it has been noted that the Albanian Kosovars’ votes (around 17% of the population) would have been enough to deny Miloseviç victory if they had made common cause with the more-conciliatory and liberal Serb opposition. The fact that the LDK boycotted these elections, however, meant Miloseviç prevailed. This might seem counterproductive to the Albanians. While it might appear to make sense to try and influence the vote in Serbia to promote the interests of parties more sympathetic to their cause (with a view, say, to having their autonomy restored) the Kosovars were by now committed to independence and nothing less.

Despite all the brutality and harassment Albanians experienced at the hands of the Serb police and army (it would be misleading to portray this period of one of untrammeled peace; there was violent repression), to have a more moderate Serb leadership restore their civil rights (and Serbia viewed more favourably by the international community as a result) would have damaged their cause for complete separation. It has, furthermore, been suggested by some commentators that Miloseviç rewarded this passive support by tolerating the growth of parallel Kosovar institutions. (Dejan Guzina, ‘Kosovo or Kosova-Could It Be Both? The Case of Interlocking Serbian and Albanian Nationalisms’, in Bieber and Daskalovski 2009, 40; Vickers 1998, 268 has also discussed this angle)

So this was the situation in the first half of the 1990s, while the rest of the world was watching Croatia and Bosnia and paying little attention to Kosovo. The obvious next question is: what changed? Well, for starters, the war in Bosnia came to an end in 1995 with the Dayton accords (see last post). The status of Kosovo was completely ignored in these negotiations and undermined the idea behind Rugova’s policy of passive resistance, that if Kosovo’s Albanians behaved themselves nicely the international community would reward them by supporting their cause. (Ker-Lindsay 2009, 11) In fact, it just seemed to have made Kosovo easier to ignore, and the obvious implication of this was that only an armed uprising would make them difficult to ignore. Thus, support began to grow for the relatively-small Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA, in Albanian: Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës or UÇK) which had been advocating insurrection against the Serbs since the early 1990s but numbered no more than 200 members.

In the spring of 1996, the KLA began to attack Serb police and Serbs who had moved into Kosovo from other parts of the former Yugoslavia where they weren’t welcome anymore. At first, these attacks were relatively small scale but, as often happens in cases such as this, the over-reaction of the Serb authorities to the KLA’s attacks turned many ordinary Kosovo Albanians, hitherto bystanders or supporters of Rugova’s passive resistance, into active supporters of the KLA. 1997 was a crucial year. In the spring of that year, an almost-total collapse of government in neighbouring Albania occurred, as the chaotic changeover from communism to capitalism caused a proliferation of unsound financial schemes that bankrupted much of the population and turned them against the ruling party. The army and police abandoned their posts and much of the country fell under the control of criminal gangs. An upshot of all this was that a huge number of military-grade weapons disappeared and were sold off to the insurgents in neighbouring Kosovo. The KLA were suddenly very well armed indeed, and were not slow to use their newfound arsenal.

The region of Drenica in central Kosovo was a particular stronghold of the KLA, and for long periods was regarded almost as a no-go area for Serb police. The KLA’s leader in this area was Adem Jashari (below), a figure who has subsequently come to be seen as a figurehead for Kosovar resistance. Jashari and his followers were accused to killing Serb policemen in 1997 and tried in absentia (because they couldn’t get their hands on him) on terrorism charges. Numerous attempts to storm Jashari’s farm/compound in early 1998 failed and led to counterattacks from the KLA, all of which represented a significant escalation of the conflict from isolated guerrilla attacks to something resembling all-out gun battles. Finally, on 5 March, the Serb police, Yugoslav army and a ‘Special Anti-Terrorist Unit’ launched a full-on mortar and gun attack on the compound, killing not only Jashari but sixty family members as well, men, women and children.

There are some who argue that Jashari and his supporters were given ample time to surrender, and that they prevented people inside who wanted to surrender from giving themselves up. It is claimed, on the other hand, that the Serb forces made little or no attempt to arrest or apprehend the KLA members they claimed to be looking for, and seemed intent on killing everyone inside. I can’t pass judgement one way or the other. What can be said is it was a terrible loss of life, that the political fallout was decisive for the Kosovo Albanians, and that it marked the beginning of all-out war.

Prior to this, western governments had shown disdain for the KLA, the United States describing it as a ‘terrorist organisation’, and criticism of Serb actions in the region had been muted. Milošević, meanwhile, was riding high. The Dayton agreement had allowed him to present himself as an international diplomat and statesman of consequence to his own people, and he won the 1997 presidential election with ease. Western disdain for the KLA had led the Serb leader to believe he was implicitly being given a more or less free hand to clamp down in Kosovo.

But he was wrong.

Intensified fighting followed the killings at Jashari’s compound, and western governments, who had been busy basking smugly in the glow of their achievements at Dayton, began to sit up and take notice to what was going on in Kosovo. Richard Holbrooke, who had been so central to the Dayton talks, visited Kosovo in May 1998 and was photographed meeting KLA members (below), not necessarily an endorsement but a significant step away from branding them terrorists beyond the pale. There is a lot of literature around alleging KLA’s funding by organised crime among the Albanian diaspora, of western intelligence services (German and American especially) training and funding KLA recruits, etc. I am not going to go down that rabbit hole here. Some of it may be exaggerated but a lot of it does not look too far-fetched. There is no doubting there was a considerable about-turn taking place among western diplomats at this time in their attitude towards the fighters, while their numbers were swollen by new recruits both from inside Kosovo and among Kosovars returning home from abroad.

The Russians, always instrumental in convincing the Serbs to do anything, got them to sit down with representatives of the more quiescent Albanians in May, and Rugova went to Belgrade to meet Milošević for the first time. The Russian initiative paved the war for a group of around 50 diplomats and observers to establish a mission to observe what was happening on the ground and ensure that the Serb authorities were maintaining basic human rights standards in their treatment of the Albanian population. They weren’t. But then again, neither were the KLA, but more of that later. Although the KLA were making impressive gains throughout the country in the summer of 1998 and causing massive problems for the Serb police and army (they killed around 80 police and 60 civilians over the summer) what caught the west’s attention at this juncture was almost exclusively the crimes of the Serbs.

It must be recalled that this was only a couple of years after the west’s inaction had allowed the Srebrenica massacre, among other horrors, to occur, and there was an acute sense of shame at the dithering which had given the Serbs free-rein to ethnically-cleanse large parts of Bosnia and claim it as their own in subsequent negotiations. There was also widespread resentment towards the Milošević regime for the ruthless brand of realpolitik it practiced, and for what can only really be described as his diplomatic outmaneuvring of western governments during the crisis. The observers who went to Kosovo in July 1998 reported numerous human rights violations, culminating in the execution of 21 villagers near the village of Gornje Obrinje in September 1998, which was documented by Human Rights Watch and journalists. This event spurred the UN to issue a Security Council Resolution (1203) the following month, which condemned such actions and once again called on both sides to eschew violence in the pursuit of their ends. The arms embargo which had been lifted Dayton was had been reimposed in March of 1998, and the reimposition of further trade sanctions were threatened if the Serbs continued attacking civilians in Kosovo.

The UN resolution also provided for a new organisaton, the Kosovo Verification Mission (KVM), larger and more extensive than its predecessor, to keep an eye on developments and ensure both sides were keeping to commitments they had made previously. In practice, sympathy abroad had swung decisively in favour of the KLA at this stage and it was almost-exclusively the Serbs who were being watched for evidence of war crimes. Unfortunately, there were more horrors to come, but before we get to them, it’s worth taking a moment to look more closely at the KLA and their strategy, and the way they conducted the war. Having started out as a guerrilla army carrying out intermittent attacks on police and army personnel, the KLA, realising they could never win a conventional military conflict with the Serb forces (setbacks throughout the late summer), had by the end of 1998 shifted their strategy to deliberately provoke the Serbs into committing atrocities in the hope that it would force the international community to intervene. Only intervention from outside, it was reasoned, could help them achieve their goal of independence, and everything was done to get the west (the Americans particularly) on their side.

One of their senior political advisors, Xhavit Haliti (below left), would later recall the KLA removing any symbolism relating to communism in their uniforms, shaving their beards so they wouldn’t look too Islamic, changing from the fist salute to the flat-handed version, all to make themselves more appealing to the Americans. Haliti is widely regarded as one of those instrumental in the founding of the KLA in the early 1990s, an astute strategist who spent many years in exile collecting donations for the cause. Forced to flee abroad for their political activities inside Yugoslavia, exile was a common experience for many of the KLA’s activists in their youth, and many of this group became known as the ‘Planners in Exile’, in contrast to Rugova’s pacifist group that stayed in Kosovo. Another of these planners in exile was Hashim Thaçi (below middle), who had grown up in the same Drenica region where Jashari had lived and died. He fled to escape arrest and studied in Switzerland for several years, during which he slipped back and forward across the border into Kosovo to prepare his allies there for what he saw as the inevitable battle ahead.

Activists like Haliti and Thaçi who had spent much time in exile knew that winning independence from the Serbs was as much about raising funds and winning influence abroad as it was about winning battles on the ground in Kosovo. Another group within the KLA, represented by Ramush Haradinaj (above right) is characterised by Henry Perritt as leading a faction he calls the ‘defenders at home’. (Perritt 2008, 17-18) This distinction is perhaps overstated by Perritt (Haradinaj, after all, spent much to the 1990s in Switzerland as well) but is useful in stressing a difference between those who were concerned with broader political strategising on the one hand, and those like Haradinaj, who focused more on the military logistics of physically defending their people from the Serbs.

All of these men have been accused of involvement in organised crime and for being involved in the perpetration of war crimes. Western military intelligence has been aware of links between KLA and the Albanian mafia for years, alleging that Thaçi and Haliti have been at the heart of a “mafia-like” network responsible for smuggling weapons, drugs and human organs during and after the war. The KLA is widely reported (by Human Rights Watch for example) to have carried out killings of Serb civilians and Albanians they considered to be collaborators with the Serbs. A special court was established in the Hague in 2017 to charge those responsible for war crimes and, at the time of writing (September 2020), Thaçi himself (now president) has just been indicted. A few individuals were also indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. These included the aforementioned Ramush Haradinaj, who had to resign his post as Prime Minister of Kosovo in 2005 to face charges of war crimes. He was acquitted and would later serve another term (2017-2020) Many of these trials and acquittals have been surrounded by controversy concerning intimidation and claims that Kosovo’s post war leaders have made it almost impossible for prosecutors to find witnesses willing to testify against senior figures in the KLA, many of whom went on to hold senior positions in the government.

Fear is not the only factor at issue. The disconnect between the perception of such figures in the eyes of international law as criminals on the one hand, and their reputation back home among their own people, as national heroes, is evident. When Haradin Bala, for example, one of the few KLA members convicted by the ICTY for the killing of Serb civilians, died in prison in 2018, the Kosovo parliament held a minute’s silence. This phenomenon is noticeable, incidentally, in many former Yugoslav republics. There is no doubting that Serb civilians were killed and mistreated, but for one reason or another this received far less attention in the west than the atrocities the Serbs committed against the Albanians. These continued even with the presence of the Verification Mission in Kosovo. Milan Milutinović, the President of Serbia at the time, being interviewed by British television, made what must be one of the great understatements of all time:

What ‘too far’ meant in practice was brought home with awful brutality in the middle of January 1999 when the village of Račak in southern Kosovo, an area of KLA activity, was attacked by Serbian special forces. After initial difficulties gaining access to the area, the international monitors managed to reach the village on 16 January, finding the bodies of 45 civilians (including a 12-year-old boy and three women) many of whom appeared to have been shot at point blank range. The American head of the KVM wasted no time in calling a press conference to castigate the Serbs for what he described as ‘an unspeakable atrocity’ and ‘a crime very much against humanity’. The Serbs claimed that the dead had been KLA members, and their uniforms and insignia removed after their death and replaced with civilian clothes to fool the world. A forensic examination by a Finnish team on behalf of the EU found no evidence for this.

The political fallout was ultimately decisive. The UN Security Council condemned what happened at Račak as a ‘massacre’. Public opinion in the west (already unsympathetic to the suffering of Serb civilians) swung even more decisively behind the Kosovo Albanians. NATO began to threaten Yugoslavia with air-strikes and ground troops in Kosovo. These threats compelled the Serbs to attend a series of negotiations at the Château de Rambouillet outside Paris in February, at which all the leading Kosovar Albanians attended (from both the KLA and Rugova’s faction), although Milošević stayed away, sending instead the more junior Milutinović in his stead. From the very start, negotiating positions seemed to preclude a deal. The Albanians refused to remain under the thumb of the Serbs while the Serbs would not countenance the presence of any outside troops in what they regarded as their sovereign territory.

It is fairly clear in retrospect that a great deal of ill will had accumulated towards the Serbs by this point. The United States, the UK and Germany in particular (although less so France) clearly leaned towards the Albanian side in the negotiations, and it was essentially a process of bending the Serb leadership to their will. The Albanians too, had to make concessions, but in this Thaçi emerged as a pivotal figure, representing a bridge in the eyes of western diplomats between the hardliners in the KLA who would accept nothing less than full independence, and those willing to settle for a more limited form of autonomy. The talks went on far longer than planned in an effort to bring both sides together, but in the end the proposals for a NATO-administered Kosovo (still within Yugoslavia but mainly only in theory) and a force of 30,000 NATO troops in the area and legal immunity for these troops, were rejected by the Yugoslav government, who were backed up by Russia.

Which, when you think about it, isn’t strange. While no doubt something had to be done to prevent further bloodshed in Kosovo, the Rambouillet (dis)agreement was formulated in such a way that it is hard to imagine any country accepting it. Certainly the demands being made of the Serbs, to allow foreign troops into their territory, would never be countenanced by the British in Northern Ireland or the Spanish in the Basque Country or Catalonia (it interesting to note that it was a Spaniard, Javier Solana, who was leading the sabre-rattling against Serbia). There is also the fact that threatening to punish a country in the way Serbia was threatened by NATO if it didn’t sign Rambouillet, would have rendered the said agreement void under the Vienna Convention in any case.

The conditions insisted upon by NATO were in fact so onerous that it has been suggested by many commentators that they were made deliberately unacceptable so as to force the Serbs to reject them and provide a justification for NATO to bomb Yugoslavia. Bill Clinton himself is reported to have commented at the time that, if he had been in Milošević’s shoes, he probably wouldn’t have signed the agreement either. This begs the question then: why was NATO so keen now to bomb the Serbs when the west had dithered so long over intervening in Bosnia a few years earlier? The welfare of civilians in Kosovo is not a credible explanation, given the relative indifference to civilians in Bosnia, not to mention the civilians in Afghanistan and Iraq the same countries would soon be massacring by the thousands. The aforementioned resentment at having being diplomatically outdone by the Milošević regime no doubt played a role. The fact that Yugoslavia was the last (besides Belarus) state in Eastern Europe that had not been brought into the neo-liberal fold of American hegemony has also been cited by Noam Chomsky as a factor in motivating the attack. Either way, he states, ‘the real purpose of the war had nothing to do with concern for Kosovar Albanians’. (Chomsky 2006)

Events moved fast in the aftermath of Rambouillet. Within days, international observers were withdrawn and NATO started bombing Yugoslavia on 24 March, within a week of the failure of the talks. This campaign of bombardment would go on for ten weeks. Its ostensible goal was to induce the Serbs to accept a settlement similar to that agreed with the Albanians at Rambouillet, in other words, to get the Serb forces to leave and prepare the ground for UN troops to move in and administer Kosovo separately from the rest of Yugoslavia. The U.S. and its lapdogs (sorry, allies) expected Yugoslavia to capitulate to these demands quickly, but Milošević did not. It is hard to know what he was thinking at this stage. Were the Serbs hoping the Russians would step in to help them? They had been implacably opposed to the air-strikes and (along with the Chinese) had voted against a Security Council resolution to authorise it, but Russia at this stage in the late 1990s (before Putin took over in 2000 and started to beef it up again) was a shadow of its former Soviet self, militarily, financially and diplomatically in no fit state to take on the west. It has been speculated that Milošević was hoping that the west’s resolve would falter if he stood out long enough without agreeing to an outside. The air-strikes, after all, were a sign that the Americans especially were very very reluctant to send ground troops in and take Kosovo by force. Perhaps the Serbs thought they could, as they had succeeded in doing so many times in Bosnia, win a game of chicken and extract a much more favourable settlement in the process. But it was ordinary Serbs, of course, who had to pay the price for this risky strategy.

As noted above, two members of the UN Security Council voted against NATO’s attack on Yugoslavia. This made it illegal. This is not to say that the world should have shrugged its shoulders and done nothing, but international law (the UN charter in this case) expressly prohibits the use of force by UN member states to resolve disputes unless the Security Council authorises it or a country is acting in self defence. Neither of these conditions applied in this case, and NATO’s decision to just ignore the UN because it didn’t suit their objectives was an appalling destructive act, the consequences of which we still live with today. NATO’s ‘New Strategic Concept’, which essentially meant fatally undermining the whole system of checks and balances at the United Nations that had prevented conflict between the world’s largest military powers for a half century.

Certainly these could be unwieldy and rendered effective response to crises difficult at times (Bosnia being a perfect example, Rwanda another) but a dangerous new world was entered with NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia, in which there was no longer any agreed-upon framework for preventing the militarily-strongest countries from invading whatever countries they liked and justifying it on whatever spurious grounds they liked. This would be seen again in the United States’ attack on Iraq in 2003 (again, without a Security Council resolution) on the grounds that they had weapons of mass destruction and were somehow involved in 9-11. And of course, seeing the United States doing whatever it liked with more or less impunity, states like Russian and China lost confidence in the idea that any legal framework could restrain them, and accordingly started to flex their own muscles. No wonder North Korea feel they have to have nukes.

In the case of Yugoslavia, the justification was that, even if bombing was illegal, it was morally justified in order to prevent a humanitarian disaster. You could of course justify almost any military action (or indeed any illegal action whatsoever) on these grounds if your logic is twisted enough. This is not to dismiss the idea of humanitarian intervention out of hand, but simply to argue that such intervention should emerge from a consensus at the UN. Another problem with the ‘humanitarian intervention’ argument is that the bombing campaign itself caused a humanitarian disaster. According to Human Rights Watch, who have backed up their statements with detailed evidence, between 489 and 528 Yugoslav civilians were killed by the campaign, around 60% of these in Kosovo. Nor were all of these Serbs. NATO aircraft bombed a column of Albanian refugees near Koriša in the south of Kosovo in May, killing 87.

Some of the targets were hardly military targets at all. The television station in Belgrade was bombed, killing sixteen civilians. Amnesty International have described this as a war crime. It was justified by NATO on the grounds that it was broadcasting propaganda, by which logic you could justify bombing most television stations in the west. Meanwhile in Kosovo, the NATO campaign led to a huge exodus of Serbs who, as we have seen in the last post, were already dwindling as a proportion of Kosovo’s population. Human Rights Watch have estimated that at least 150,000 fled in the six weeks after the NATO-led ground troops, Kosovo Force (KFOR), entered Kosovo on 11 June. Most of the Serbs that stayed behind were internally displaced into a few enclaves, especially in the north close to the Serbian border.

There is, incidentally, no contradiction in noting all of these depredations while also thinking that the Serbs actions were also appalling. I don’t want to fall into banal platitudes about ‘all sides being equally bad’ (which are so common among people that just couldn’t be bothered to learn the intricacies of a conflict) and this doesn’t imply any weighing-up or comparison of atrocities, but really all sides (including NATO) conducted themselves reprehensibly.

As noted above, KFOR entered in June and the Yugoslav forces withdrew, Milošević having finally thrown in the towel in early June, realising that the west meant business and that the Russians were not going to offer anything more than moral support. A UN resolution was finally adopted authorising KFOR and creating a civilian administration, the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) which still exists to this day, albeit with much more limited areas of responsibilities than it had in the years after the war, when it took over the running of Kosovo from Belgrade. In this way, Kosovo became a de-facto separate state from the rest of Yugoslavia, which would itself split up and soon become Serbia. Although the UN resolution (still legally binding in theory) recognised Serbian sovereignty over Kosovo, the ‘Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija’ as it is still described in the Serb constitution, has in practice gone its own way, declaring independence in 2008 (recognised by around 100 other countries) and enjoying most of the trappings of a fully-independent state since then.

I hope to look at the post-war history of Kosovo more closely in a future post, the activities of the leaders (we have briefly examined the head honchos) who have dominated this period and the ongoing controversies surrounding the legacy of the war and crimes committed by both sides. But a post on this blog wouldn’t be complete without some cursory examination at least of the role played by religion and political Islam in the Kosovo conflict. This will be cursory because that role (even more so than Bosnia, where it didn’t play as big a role as Serb propaganda claimed) was very minor indeed. Similar to Albania, Islam in Kosovo has played very little role in identity formation. The part played by the Orthodox church in Serb nationalism of the 1980s and 1990s offers a stark contrast. This relative unimportance of Islam is reflected in the fact that the small number of Serbian and Roma Muslims in Kosovo were just as likely to be targeted by the Albanians for harassment during and after the war as their Orthodox peers. (Bieber and Daskalovski 2009, 185)

While political Islam offered a potential source of support and money in the 1990s (as it had in Bosnia to a limited extent), both the LDK and the KLA were profoundly wary of aligning themselves with these forces. Bujar Bukoshi, a close ally of Rugova and Prime Minister of the parallel state that the LDK ran from 1991 to 2000 remarked:

We knew that accepting help from Iran or Saudi Arabia would be the death knell of our effort to engage the West. I had an offer from Iran when things were so desperate that “we were seeking help from Eskimos and penguins.” I refused, because I knew it was a trap . . . Serbia was rubbing its hands in anticipation that fundamentalists would become involved in the Kosovo struggle. From the beginning, Serbia had always argued to the West, “We protect you from the Muslim hordes—the atheists who will extinguish Christianity.” We did not want to fulfill Serbian dreams. (Perritt 2008, 144-5)

The KLA likewise, had its roots in small Marxist groups of the 1980s and by the beginning of military activity against the Serbs in 1997 had jettisoned even this to focus almost exclusively on nationalism as an ideology. Volunteers came from Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries in the spring of 1998. By the summer there were around 40 of these, in addition to some local Albanian fighters who also identified themselves as mujahideen. Initially willing to accept help from any source whatsoever, the KLA asked these Islamist fighters to leave when the CIA warned them that they must disassociate themselves from them. This contingent was largely put paid to in the early morning hours of July 18 when the Yugoslav army ambushed a column of KLA and mujahideen trying to cross the mountainous border region between Albania and Kosovo, killing 24 foreign fighters, mostly from Saudi Arabia. Human Rights Watch have suggested that the jihadists were deliberately led into a trap by the KLA to get rid of them, having already refused to leave at the behest of the leadership. Survivors later told of the KLA leading the group into an ambush and then fleeing. (Abrahams 2015, 262-3) So much for the Kosovan jihad.

There have of course been attacks on Serb Orthodox churches and other symbols, such as the Visoki Dečani Monastery (quite close to the aforementioned ambush in fact), which Albanian mobs have thrown molotov cocktails and hand grenades at over the years, and which is under 24 hour guard by KFOR. While these might appear motivated by religious ideology on the face of it, they have more to do with an identification with the Serbian church as potent symbols of the Serbian nation, and their attempted destruction an attempt to erase every trace of a Serbian presence in the area. This is one of the saddest aspects of the Kosovo story really, that no possibility of coexistence seems to emerge. There is no sense in which NATO’s intervention resolved the conflict really. It simply reinforced the idea that it was a zero sum game, that whatever one ‘side’ gained must of necessity be at the expense of the other. Either the Serbs banished all the Albanians, or vice versa.

STOP PRESS:

A month after the publication of this post, Hashim Thaçi resigned as president of Kosovo to face war crimes charges in The Hague. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/05/hashim-thaci-kosovos-president-resigns-to-face-war-crimes-charges-in-the-hague

FURTHER READING:

Fred Abrahams, Modern Albania : From Dictatorship to Democracy in Europe (New York University Press, 2015)

Florian Bieber and Židas Daskalovski, Understanding the war in Kosovo (London: Routledge, 2009)

Noam Chomsky, ‘On the NATO Bombing of Yugoslavia’, interviewed by Danilo Mandic, RTS Online, April 25, 2006. https://chomsky.info/20060425/

Tim Judah, Kosovo : What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2008)

James Ker-Lindsay, Kosovo: The Path to Contested Statehood in the Balkans (London: IB Tauris, 2009)

Henry Perritt, Kosovo Liberation Army : The Inside Story of an Insurgency (University of Illinois Press, 2008)

Miranda Vickers, The Albanians : a Modern History (London: IB Tauris, 1995)

Miranda Vickers, Between Serb and Albanian : a history of Kosovo (London : Hurst & Co., 1998)

[…] A contemporary history of the Muslim world, part 22: Kosovo #2 […]

LikeLike