As I publish this it’s twenty-five years since the events of Srebrenica in July 1995 and seems an apposite time to look back at the Bosnian war. Many people remember the wars in Yugoslavia as starting in the early 1990, but there is a good argument to be made that the beginning of the end came earlier, in Kosovo, around 1987, with the events discussed at the end of the last post. I had planned to look at events in both Bosnia and Kosovo in the 1990s in a single post, but far too much happened to fit it all in, so instead we will look at events in Kosovo after the visit of a certain Serb technocrat in 1987 in the next post, and focus here on the crisis that developed in Bosnia and Herzegovina following the secession of Slovenia and Croatia in June 1991 and the two wars those new countries fought against the rump Yugoslav state (in effect, the Serbs). One of these (the Slovenian) was relatively short (ten days, 75 casualties) while the other (in Croatia) was far more drawn-out and bloody, lasting over four years (although most intense in the summers of 1991 and 1995) and killed over 20,000 soldiers and civilians.

The events that we will examine in Kosovo played a part, especially in the Slovenians’ growing unease at the high-handedness of the Miloseviç regime, Kosovo acting as a sort of grim salutary reminder of what might befall them if they didn’t get out from under Belgrade’s thumb. Croatia was no less eager, and harboured a well-organised and passionate nationalist movement waiting in the wings for their opportunity. This came with the first multi-party elections in the summer of 1990, won by the Croatian Democratic Union, the HDZ (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica) under the leadership of its founder Franjo Tuđman, who immediately set about preparing for independence.

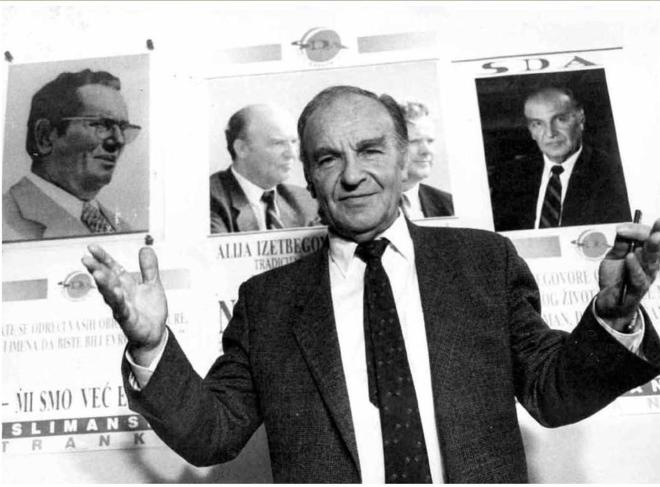

Whereas leaders like Tuđman had long held independence as the objective, and the Yugoslav crisis offering a way of achieving this goal, things were somewhat different in Bosnia following their elections of 1990. Firstly, the republic, with its complex ethnic makeup, was governed using a different system. Voters chose seven members of a presidium, with two places each being reserved for Muslims, Serbs and Croats respectively, while the seventh represented ‘others’. The Muslims’ ‘Party of Democratic Action’, the SDA (Stranka Demokratske Akcije) won most seats in the assembly and its leader, Alija Izetbegović, who we saw in the post before last being released from prison the year before, became president of the presidium.

In the polarising elections of this time, other members of the presidium invariably represented those factions among the Serbs and Croats who wanted either to remain part of Yugoslavia or secede to the new Croat state. Nor was the Muslim party unambiguously committed to independence itself. Izetbegović led a broad church, attempting to keep together different groups who often identified themselves as Bosnian Muslims only in the ethnic, secular sense we discussed two posts back. Conservative religious Muslims did make up a portion of the SDA but only a portion, and Izetbegović found himself in the unenviable position of trying to balance the interests and demands of these competing groups with often incompatible objectives. To characterise the Muslim faction as uniformly seeking independence for a Bosnian state to be dominated in some sense by Islam is wholly inaccurate. There were no doubt some who wanted this, but they were far from prevalent.

Even Izetbegović, who had been imprisoned a decade earlier for his Islamic Declaration, which seemed to advocate an intrusion of Islam in the political realm, by this time placed far less emphasis on religion and, by his actions and statements, genuinely appears to have sought arrangements that would reflect the aspirations of the three different ethnic groups in the country. Ambiguity remains, however, about the extent to which he envisaged the future Bosnian state being an Islamic one. He seems to have laid stress on different aspects depending on his audience; for western journalists, the emphasis was on democracy and pluralism, while he could speak with great passion of the need for a Muslim state when speaking to Muslim audiences.

He faced a number of rival factions within his party and clearly a part of his strategy of being all things to all men was aimed at keeping these disparate interest groups together. One the one hand there were those who thought him too coy about the his ambitions for Bosnia’s Muslims, and that they should explicitly work towards an independent state that was, if not exclusively, then primarily intended for the Muslims as a homeland. This current (with its implicit corollary of expelling non-Muslims from large swatches of the country’s territory) gained currency in the early stages of the war especially, in response to atrocities committed against Muslims. Its adherents were sometimes known as the ‘Sandžak faction’ because many of them came from that region with a high concentration of Muslims in Serbia and Montenegro, sandwiched in between Bosnia and Kosovo. Its leading figures were Ejup Ganić and Sefer Halilović (below), the latter being placed in the charge of the army in the first years of the war, and more of whom later.

While influential for a time, this aspiration to an explicitly Muslim state was never dominant in the SDA and seems to have subsided after 1993, especially with the appointment as prime minister of Haris Silajdžić (below). Silajdžić, a close ally of Izetbegović and his first minister of foreign affairs, lobbied hard for a multiethnic, secular vision of a future Bosnia.

While arguing for a more explicitly Muslim state, it should not be understood that the aforementioned nationalist faction were Islamists or interested in a confessional state of any kind. Two posts back I explained the notion of ‘Muslim’ as an ethnic identifier, a national identity, rather than a religious one, and that is what is meant here. Indeed, Bosnian Muslims were on the whole generally secular. A poll in 1985 found that only 17% described themselves as believers in Islam. (Sandowski 1995, 13) This no doubt rose throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s; nevertheless support for the kind of fundamentalist or Islamist ideology that Serbian propaganda presented as widespread, was in fact very limited. To the extent that it existed, it will be examined below.

Izetbegović also faced a rival faction of what might be called ‘liberal nationalists’, led by Adil Zulfikarpašić and Muhamed Filipović (below), who were more open to trying to rescue some semblance of Yugoslavia as a confederation. In the summer of 1991, they had med with representatives of the Bosnian Serbs’ party, the SDS and their leader Radovan Karadžić (more of whom below), and agreed an arrangement whereby Bosnia would remain in a Yugoslav confederation with Serbia and Montenegro, in return for which the Serb areas of Bosnia would not break away and large parts of the Sandžak would be given to Bosnia as well. Such a plan was not as disadvantageous to the Bosnians as might first appear. While it might risk domination by the Serbs, it did mean remaining in a unitary state with the Muslims of the Sandžak and Kosovo, giving them proportionally greater influence with the departure of the Slovenians and Croats.

The plan received the consent of Milošević himself, but events in Croatia, where war broke out in March 1991, rendered much of the negotiating and manoeuvering of Bosnia’s Muslims moot. While Izetbegović had initially backed the plan for some kind of loose association with the rest of Yugoslavia, the brutality with which the Serbs attempted to keep Croatia in the federation by force led to a growing realisation that remaining in a truncated Yugoslavia would involve being a puppet state totally dominated by the Serbs. Opposition to the plan hardened and Izetbegović was forced to abandon it. Plans, supported by the Macedonians, for a union of independent states (whatever that might mean) likewise came to nothing. These pressures pushed Izetbegović more unambiguously in the direction of full independence for Bosnia and generally empowered the more conservative Muslim elements within the SDA. Zulfikarpašić and Filipović, meanwhile, would stand by Izetbegović and participate in his government during the coming war, but left the SDA and founded their own party, the MBO (Muslim Bosniak Organisation) to cater to more secular, liberal Muslims.

The reality for Bosnia was that they were in a situation of reacting to circumstances created elsewhere, of making the best of a rapidly changing situation that the Serbs and Croats were driving forward. As the Croat war unfolded, the situation in Bosnia only became more and more foreboding. Even multi-party elections were not greeted with any great enthusiasm, given that most Bosnians knew that the party system which emerged would be one organised along ethnic lines (even if new rules forbid parties using ethnic identifiers in their names) and would likely bring paralysis and instability. In the words of Viktor Meier:

The politicians and populations of all three nationalities would have preferred it if there had still been a modestly authoritarian but “liveable” Yugoslavia, which would cover up national antagonisms and render difficult decisions unnecessary. (Meier 2014, 191)

There seems to have been a failure by many on the Muslim side to realise just how committed to war—and carving out enclaves by force of arms—the Serbian side already were. Meier again notes that even now Izetbegović seemed to believe that the Yugoslav army would act to keep the peace in Bosnia, rather than taking sides. (Meier 2014, 200) By the end of the 1991, however, it became obvious that the army was moving into position to defend the Bosnian Serbs and placing heavy weapons around the major towns and cities. Instead of waiting to see what arrangements might emerge from political processes in Bosnia, the now Serbian-dominated Yugoslav army was clearly acting to make sure Bosnia could not achieve independence.

The spring of 1992 was fateful. The international community recognised Croatian independence in January. There wasn’t much of a Yugoslavia left to remain part of by this stage and the inevitability of war had dawned on Bosnia’s Muslims as large swathes of the republic’s territory were now under de facto Serb control. It is an open secret that Tudjman and Milošević had secretly agreed at a meeting the previous year to carve up Bosnia between them. Izetbegović remarked that having to choose sides between them was like having to choose between leukaemia and a brain tumour. The priority for Bosnia’s Muslim leaders became putting off war for as long as possible while they tried to purchase arms and prepare to defend themselves against the coming onslaught. While the Serbs and had been arming themselves for some time, the Muslims had neglected to prepare militarily in any meaningful way. They were hampered in their efforts by an arms embargo imposed by the UN in September which was applied to all sides, which effectively favoured the Serbs, who were already armed to the teeth, and prevented the Muslims from (at least legally) obtaining the weapons to defend themselves.

It should likewise be remembered that, while people throughout Bosnia were rapidly dividing into camps, driven largely by fear and the onrush of events, there were many, especially in a big city like Sarajevo, who weren’t clambering for war but out protesting for their politicians to sit down and get their heads together to prevent one. Just before the war began, there were plenty of Serbs and Croats who supported Bosnia’s government and Izetbegović. The conflict was not purely ethnic, which makes sense when you consider how many people had overlapping identities, a legacy of post-war Yugoslavia when for many people religion and ethnicity didn’t matter all that much and 30-40% of all marriages in urban Bosnia were mixed. (Pinson 1996, 1-2) Non-nationalist parties (mostly former communists and assorted liberals) actually won around 25% of the vote in the 1990 elections, but because of the system adopted, ended up with very little power. (Burg and Shoup 1999, 50-51)

The above photo is from the massive demonstrations on the 5-6 April 1992, when over 100,000 of all nationalities marched for a peaceful resolution of the conflict. On the second day, the protesters were marching past the Holiday Inn, where the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić held court, when they were fired on by snipers from somewhere on the top floors of the hotel. Two women, Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić were killed, and are often cited as the first victims of the Bosnian war, although even in this the other side have their own version of events. Serbs regard Nikola Gardović, killed by Muslims at the wedding of his son on the 1 March, as its first victim. Either way, things quickly spiraled out of control. Large sections of Sarajevo had already been taken over and barricaded by armed Serb militias in the wake of the wedding shooting, which had taken place at the same time as a referendum was held by the authorities, boycotted by the Serbs who saw it as a hostile act, voted to declare independence, which they did on the 3 March.

Demanding that the authorities do something about the barricades and armed militias that were taking over their city had been among the protesters’ main reasons for gathering. Some seemed to live under the delusion that Izetbegović’s government had the capacity to do this, or even that the Yugoslav army would intervene to remove them. The reality was that, by the start of 1992, large parts of Bosnia’s territory had already passed out of the control of the government in Sarajevo into the hands of the Bosnian Serbs.

While Bosnia’s Muslims may have been continued to delude themselves that war could be avoided and divided over what kind of arrangements they would seek in the new order, there was a sense of clarity among the Serbs led by Radovan Karadžić (below), who had very decided ideas of what they would and would not accept in a future state. Karadžić, a sports psychologist, environmentalist and poet before his metamorphosis into an extremist Serb nationalist, had also dabbled in embezzlement and fraud and was sentenced to a couple of years in prison for this in the 1980s before forming the SDS (Serb Democratic Party/Srpska demokratska stranka) in the autumn of 1990. It led the establishment of the so-called Serb Autonomous Oblasts (SAOs) from the autumn of 1991 onwards, establishing a separate Serb Assembly in October.

Although this is a blog about Muslims in recent history, a word must be said here about the Bosnian Serbs, who are often painted as the bad guys of the wars in Yugoslavia, almost homicidal maniacs who just wanted to kill Muslims for the sake of it. Like all such explanations, this is trite and simplistic. Certainly the Serbs were disproportionately responsible for atrocities and war crimes in the wars, but not exclusively by any means, and indeed Serb civilians were the victims of atrocities by both the Croats and Bosnian Muslims. No doubt there were some psychopaths on the Serb side who just wanted to kill Muslims out of bigotry and hatred, but a lot of the antipathy towards the other side was based on fear. Just like everyone else, Bosnian Serbs were afraid, and instead of having responsible leaders who allayed these fears and protected them from the real threats they faced, they had irresponsible demagogues who stoked these fears and exaggerated the threats in order to bolster their own power.

The Serbs made up the peasant element in the social structure of Bosnia, while the Muslims were mainly educated townspeople. Like their kin in Kosovo, the Serbs were backwoodsmen, easy meat for nationalist demagogues like Radovan Karadziç and Miloseviç, who milked the ideology of the peasant ‘folk’, offering them paternalistic reassurance that they had not been forgotten. (Benson 2014, 144)

Throughout the spring of 1992, the Yugoslav authorities quietly transferred into the army in Bosnia Serbs of Bosnian extraction and transferred out those who weren’t. One lesson that had been learned from the war in Croatia was that Serbs from Serbia proper were less committed to the fight, whereas those who either came from or had family among the Serb communities in these other republics had a personal interest in the conflict and tended to fight accordingly. In addition to these professional soldiers, there were a number of paramilitaries that had sprung up and grown with the tacit support of the Milošević regime. The most notorious of these were of course the ‘Tigers’ who invaded the country from the east and started massacring Muslim civilians there even before the official outbreak of war on April 6. But the less said about them here the better. If a picture says a thousand words, these photographs taken by the American photojournalist Ron Haviv, who accompanied Arkan’s militia and promised not to photograph them killing (but did anyway) say it all in the most shocking and depressing fashion.

And so, to war. There are many good blow-by-blow accounts. I will give here the broadest outline of events only.

The European Community (today the EU) recognised Bosnia’s independence on the same day the snipers fired on the crowds in Sarajevo. The United States extended recognition the next day. The Serbs had warned that recognising an independent Bosnia before profound changes had been made to its organisation to safeguard their rights, would be seen as a declaration of war. They were as good as their word. Eastern Bosnia was invaded, not only by the aforementioned Serbian paramilitary groups, but also by Yugoslav army reservists. The Yugoslav army followed within days and in May it discharged 80,000 of its Bosnian Serb troops, who were allowed to keep their weapons and formally constituted the ‘Army of Republika Srpska’.

The shelling of Sarajevo began on the 6 April, while Serb government officials fled the city at the exhortation of the SDS. The help of the Yugoslav army was critical in these early stages, as the Bosnian Serbs overran Muslim areas in the east of Bosnia fairly quickly. Any faint hope that a ceasefire might be arranged to allow negotiations towards a political settlement were ended by a series of events on the 2-3 May, when it looked like the Serbs might take Sarajevo, but they were fought back and then encircled by various Bosnian Muslim forces, who took many Serb prisoners. The Yugoslav army then kidnapped Izetbegović at the airport where he was on his way back from negotiations in Lisbon, demanding the release of the Serb prisoners in return for him. A deal was reached whereby the Serbs would be allowed to depart in a Yugoslav army convoy the following day, accompanied by Izetbegović’s release. The whole sequence of almost unbelievable events is narrated very well here (around 28 minutes in), including the negotiations for the president’s release basically taking place on live television.

Izetbegović was duly released, but when the Serb convoy attempted to leave, it was attacked by Bosnian forces, arguably in violation of the agreement (although the Bosnians said that they had only agreed to let the general and his aides go, not all the soldiers with their weapons). Several soldiers were killed dead and many captured, but the rest escaped and the president got home. Militarily, the incident had little significance, but politically it was a disaster which deepened the ill will and distrust on both sides and made any reconciliation almost unattainable. Having failed to take the city, the Serbs settled into a long siege and bombardment of Sarajevo. This film is a compilation of home videos filmed during the siege, and gives a very atmospheric feel of what it must have been like to live through this horrific episode:

The bombardment of civilians and other atrocities led to the UN to impose sanctions on Yugoslavia at the end of May 1992. This is as good a place as any to discuss the role played by the international community’s actions (or rather inactions) in the whole conflict. It is easy in hindsight to say that the west should have gone in with all guns blazing to protect the Muslims against the Serbs. This might, as many argued at the time, have simply made things worse; maybe not. Doing very little didn’t work very well either. This was just one of several strategic blunders were made on the diplomatic front by the ‘great powers’ who engaged in the Yugoslav crisis, primarily: the United States, Britain, France, Germany and Russia. A major problem was that the west’s response was almost always reactive, impelled by crises and particularly atrocious episodes to do be seen to be doing something to exert pressure on the Serbs, but without getting involved too deeply. Then, when the war had retreated from the front pages of the newspapers for a while, to lapse back into complacency and inaction.

Basically, the west saw the conflict in Yugoslavia as not threatening their interests either militarily or economically (it was wryly noted by observers that the Bosnian Muslims, unlike the Kuwaitis for whose sovereignty the west had supposedly recently gone to war in Iraq, did not possess oil). The United States’ reluctance to contribute troops to any initiative was a major factor. At the same time it frequently urged more decisive military action, using other countries’ troops, limiting their own contribution to air strikes. Those European nations who did contribute troops were afraid to expand their role or risk bombing the Serbs for fears that the Serbs would take revenge on their troops. The Serb on the other hand saw this weakness and were correspondingly bold, shockingly bold to observers, in the flagrancy with which they flouted ceasefires and agreements with the UN.

On the whole, international efforts to tackle the Yugoslav crisis can be characterised as incompetent rather than malicious, although for those bearing the brunt of it, it must have felt like malice at times. The sense of drift and empty threats would be fresh in the mind when it came to responding to Serb attacks in Kosovo a few years later, which we will get to in the next post. Among the many blunders made, one often noted at the outset of the conflict was Germany’s hasty recognition of Croatian independence. It is not the recognition per se that is criticised, but its timing, which did several things, all of which were inimical to creating an atmosphere in which calm negotiation might take place concerning Bosnia: firstly, it undermined the EU’s claims to impartiality, in the eyes of the Serbs at least; secondly, in giving Croatia the green light for independence, Izetbegović was left with little choice but to push for Bosnia’s independence, given the stated intention not to be left alone in a confederation with Serbia; thirdly, it made the recognition of Bosnia by the international community more or less inevitable as well, in turn convincing the Serbs that there was little point in negotiation and instead compelling them to step up their preparations for war. All of this, it is argued, could have been avoided if the Germans had held off recognising Croatia until the situation in Bosnia had been clarified somewhat.

Once war had started, efforts were ongoing to work out a peace plan. There were numerous initiatives which I don’t have space to go into here. Perhaps the closest anyone got to getting a deal was the UN Special Envoy Cyrus Vance and the EU’s representative David Owen, who proposed the division of a Bosnian state into ten semi-autonomous regions, each designated Muslim, Serb or Croat. The Vance-Owen negotiations have been criticised by Sabrina Ramet for example (Ramet 2018, 208) for recognising the Serb and Croat insurgents as equal to the Bosnian government, a sovereign government. This set the stage for a three-warring factions paradigm, each entitled to equal status in the negotiating process and to claim territorial changes, effectively rewarding Serbia’s aggression. This is Ramet’s interpretation which, while it makes sense, does beg the question: ‘what choice did they have under the circumstances?’ In order to negotiate peace, unpleasant compromises often need to be made, and this looks like one of them.

The Vance-Owen plan won the acceptance of Milošević, who then pressured the initially-reluctant Karadžić into accepting it at a conference in Athens, reportedly telling him he wouldn’t be going home if he didn’t sign. Karadžić signed, but insisted the deal would be subject to approval by the Bosnian Serb assembly back in Pale. Despite the attendance of Milošević in person, the Bosnian Serbs rejected the peace plan comprehensively in May 1993, first in their assembly and then in a referendum. Furious, Milošević said he would stop supporting them with arms and supplies, which he had denied doing up to that point.

It should be noted here that the image sometimes given of Milošević prepared to back the Serbs in Bosnia and the Krajina to the hilt no matter what, is inaccurate. In fact, he would show that he was only too willing to cut them loose and sacrifice their interests when it served his larger political purposes. He said explicitly to Milan Babić, leader of the Krajina Serbs in 1992 that it was not possible that all Serbs should be accommodated within the Serbian state, and that the Serbs outside Serbia proper could not hold those within the homeland to hostage. (Burg and Shoup 1999, 90) He became increasingly impatient with the refusal of Karadžić and his people to reach a compromise as the war dragged on and it became clear that the west, for all its reluctance to intervene, was not going to let them just keep whatever they had conquered by force. Nevertheless, despite his threats, the rift was soon healed and the Serbian government continued to support the Bosnian Serbs after the failure of the Vance-Owen plan.

In the end, the not-so-great powers managed to annoy both sides more or less equally. Ramet has suggested that the British, and even more so the French, were so opposed to lifting the arms embargo and helping the Muslims arm, and so opposed to substantive military action, that they were enacting an essentially pro-Serb policy. Relations between Bosnian government and the UN poor, with accusations that they were allowing their own people to suffer in order to gain sympathy and assistance from the west. (Burg and Shoup 1999, 161-162)

The Serbs, meanwhile, accused the west of effectively taking sides in the conflict, and argued that the welfare of Serbs outside Serbia was their own business. While war crimes are everyone’s business, and not to deny the rights of the component states to independence, but there does seem to be a whiff of double standards in the way the west created an ad-hoc legal framework for the breakup of Yugoslavia and the recognition of the new states when they would never countenance separatism at home. Those who wanted to keep Yugoslavia intact or at least negotiate redrawn borders, could be forgiven for remarking that the west has never shown a similar desire to facilitate the Scottish, Irish, Catalan, Basques or many other peoples in their desire for independence from Britain, Spain, etc. that they showed to Croats, Slovenes, Albanian Kosovars etc.

Anyway, back to the war.

At the end of June, Sarajevo airport re-opened under UN supervision. The Bosnian government (I may refer to them occasionally here as ‘the Muslims’ but in fact they included some Serbs and Croats who supported the idea of a multiethnic state) and the Croats forces made some successful counter-attacks at the end of the summer, but Sarajevo remained encircled and subject to indiscriminate shelling. Bosnia’s defence in this early period of the war was in the hands of a mixture of professional government troops, militias and criminal gangs, the last-mentioned being (in the early stages at least) probably the city’s most effective defenders.

The above-mentioned Sefer Halilović would emerge as the main military leader in these early years. He had formed the Patriotic League in March 1991 and by March the following year it had around 100,000 members, mostly Bosnian Muslims who were organising to defend their people in response to the obvious military preparations of the Serbs and Croats. There was a certain amount of organisational ambiguity in the early part of the war, and overlap between the league and the ‘Green Berets’, which is a term used for other paramilitaries formed in 1991 at the urging of the SDA. There is in turn a certain degree of overlap between these paramilitaries and the criminal gangs who mobilised to assist in the defense. While Halilović was a professional soldier (he had been a major in the Yugoslav army) he gave these gangs a great deal of latitude at the outset of the war. Bosnia needed all the help it could get, and the gangsters were particularly adept at urban warfare in Sarajevo, which the Serb forces were reluctant to get bogged down in.

Among these early defenders of Sarajevo were Jusuf Prazina (below), a feared debt-collector who had formed his own personal army at the start of the war that proved highly adept at keeping the Serbs out of the city. He cultivated a sort of Robin Hood cult around himself and became a popular hero of the city’s citizens. To the Bosnian authorities, his help had been vital but he also came to be seen as a threat as his power and popularity grew. His gangs did not cease their criminal activity and as Prazina demanded positions of power in the new country’s armed forces, plots were undertaken to have him arrested. He fled to the Croat side and then abroad. His corpse was found in the Belgian countryside in 1993, although it remains unclear who killed him. Death was also the fate of Mušan “Caco” Topalović, a black market kingpin who became notorious for picking people up from the street and forcing them to dig trenches. These people, if they were Serbs, often disappeared to face a grisly end, especially if his gang fancied taking their apartment. He is suspected of responsibility for a large number of killings of Serb civilians, many corpses being found in the so-called Kazani pit north of the city, where Caco’s men would bring their victims to kill them and dump their bodies. He was killed in a crackdown on gang leaders in October 1993, many suspecting that the government found it convenient not to take him alive as he had done much of their dirty work and any trial would be a major headache for Izetbegović and co.

Ismet “Ćelo” Bajramović (above right) was another gang leader who ran a thriving profiteering racket while running the military police and the prison during the siege. Unlike his aforementioned counterparts, he survived the war, although not unscathed, His shooting by a sniper in September 1993 created a crisis for the Bosnian government when his followers took over the local hospital where he was being treated, the bullet having lodged near his heart. They threatened to cause mayhem if he died and the authorities pulled strings to have him airlifted out to Italy where he was saved by emergency surgery. The injury continued to plague him with health problems, which were reportedly the reason for his suicide in 2008.

Taming the gangs was part of a process of regularising the Bosnian forces and incorporating them all into the new republic’s national army, the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnian: Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine or ARBiH). As part of this process, Halilović was replaced as commander in June 1993, seen as far too close to the criminal elements and having made several enemies in the higher echelons of Izetbegović’s government. It is even alleged that they orchestrated an assassination attempt against him in July of the same year, in which his wife and brother-in-law were killed by accident.

None of this meant that the war was turning in Bosnia’s favour. If anything, things deteriorated in January 1993 when they found themselves fighting the Croats. The HVO (Croatian Defence Council, in Croatian: Hrvatsko vijeće obrane) was the armed forces of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, which was the self-declared independent entity within Bosnia the Croats claimed, many of whom envisaged eventual absorption into the newly-independent Croatia next door. Hitherto allies, hostilities broke out between the Muslims and Croats because the latter were unhappy with the dispensation of land to them in the Vance-Owen plan. Ramet (2018, 211) also suggests that western failure to stand up to the Bosnian Serb’s aggression likely encouraged the Croats to think aggression and territorial gains made by force of arms would be rewarded.

The outbreak of hostilities between the HVO and Bosnia’s government only made a complicated situation even more complicated. Sometimes the Croats co-operated with the Serbs against the Bosnians, sometimes they fought them; sometimes the Muslims fought with the Serbs against the Croats. (Burg and Shoup 1999, 138) The fiercest fighting took place around the city of Mostar, about 75km southwest of Sarajevo, an area from which the Croats had driven the Serbs the year before in the latter’s first major defeat of the war. Mostar was roughly 40% Croat, 40% Muslim and 20% Serb before the war and in May 1993 the HVO began to shell the Muslim eastern part of the city incessantly, eventually destroying (on 9 November 1993) the city’s famed 427 year-old footbridge, the Stari Most, which crosses the Neretva River.

The following documentary was made by the BBC’s Jeremy Bowen at the time of the siege, before the destruction of the bridge. It was subsequently shown at the war crimes tribunal and gives a good idea of what it was like to go through this hell. As is often the case, its the people who experience it directly who give the best sense of the reality of war, especially for people who have never experienced conflict directly and spout platitudes about it being caused by ‘hate’, expressing bewilderment as to why people shoot at each other. The guy talking around 9:50 gives a very succinct example of the reality, that people often have no choice but to fight in order to survive, that no-one else was prepared to help the Muslims and the alternative was being carved up between Croats and Serbs, i.e. extinction. They would keep up the fight long enough to force the west to finally intervene. His response to the final question I think says it all:

‘Where will you go if you lose?’

‘I don’t know’.

Meanwhile in Sarajevo, the city was almost completely cut off after the Serb capture of Trnovo just south of the city in the summer of 1993. But not entirely, and in fact the Serbs handed back some territory in August to UN troops. This is sometimes described as the failure to force the capitulation of Sarajevo, but it may also have been seen by the Serbs as a strategic mavoeuvure by which they got the UN to hold the territory it had won, preventing their enemy from re-occupying it. This was a tactic throughout the war by the Serbs: make what appeared to be concessions which were actually tactical retreats, compelling the UN to do the work of consolidating their redrawing of the ethnic map of Bosnia and strengthening their hand in eventual negotiations.

This strategy had its limitations, however. The shelling of the city continued, and was largely indiscriminate, a number of atrocities gradually hardening the outside world’s resolve to do something to stop them. The bombing of the Markale marketplace in February 1994 killed 68 people. The same location would again be hit in August of the following year, killing 44. In both cases the Serbs denied responsibility and in the first at least, their claims that the Bosnian army were bombing their own people to elicit sympathy from the international community were given credence by the UN observers on the scene. The consequences of the first massacre were that the UN proclaimed an ‘exclusion zone’ around Sarajevo from which the Serbs were told to move their heavy artillery. The consequences of the second massacre we will find out in due course.

The (temporary) retreat of heavy weapons from around Sarajevo was bad news for the town of Goražde, about 50km to the east, because that was where the Bosnian Serb army now focused their attentions. Goražde, which before the war was roughly 70% Muslim 30% Serb, had avoided the worst of the atrocities that had been witnessed in the early stages of the conflict, mainly thanks to a ‘Citizens Forum’ that that was formed to counter inter-ethnic violence. (Burg and Shoup 1999, 129) By March of 1994 this relative calm was shattered and the Serbs almost entirely surrounded the town, beginning to shell it into oblivion. In the week of 10 April the UN’s patience snapped and they began air strikes against Serb positions. In response the Serbs began firing at UN aircraft and helicopters and taking UN personnel hostage, as their general, Ratko Mladić, had warned they would. Another game of bluff ensued, in which the US seemed to think the Serbs might be intimidated by air strikes, but they didn’t seem to be, at least not the Bosnian Serbs. This is an important distinction, because at this stage it was becoming less and less clear that Milošević was willing to bring down the ire of the world on his country for the sake of what he clearly saw as a few stubborn backwoodsmen.

Finally the Serbs backed down, withdrew their heavy weapons and returned their hostages, then they went back on their promises, and slowly but surely the Americans got more and more fed up with their bad faith and began to side more openly with the Muslims. The French, British and Russians, however, remained steadfastly opposed to deepened involvement and Bosnian Serb attacks on UN troops increased towards the end of 1994. Morale was low and there was serious talk of UN withdrawal. This likely scared the Serbs, who had been manipulating the UN presence to consolidate military gains, not to mention skimming off a great deal of food and fuel supplies from the UN meant for the Muslims. They weren’t really keen, therefore, on the idea of the UN pulling out.

By the start of 1995, some commentators, especially in Britain and France, were declaring the war practically won by Serbia and that any action against them would be pointless and foolhardy. Those with inside knowledge, however, noted the Bosnian Serbs were running out of money, unable to even pay their officers, heavily dependent on stealing supplies from the UN, and generally low on morale themselves. Serbia itself, furthermore, had been heavily hit by the economic sanctions imposed on the country since 1992; its economy in terms of GDP contracted almost 60% between 1990 and 1993. You can always tell an economy is tanking when their banknotes are covered in zeros, and the hyperinflation experienced in Yugoslavia was one of most severe the world has ever seen, prices increasing more in an hour than they do in a year in many countries.

At the same time, Bosnian and Croat forces were becoming better armed and trained as a result of help from the US and Islamic countries. They had signed a cease-fire in February 1994 and the Croats had developed an efficient and productive arms industry to rival that of the Serbs. In the summer of 1995 the Croats launched a crushing offensive against the Serb-held areas in Croatia, the so-called Krajina, and integrated all of these areas into their national territory. The Croat victory was also a huge boost to the Bosnian Muslims’ cause now that the Croats were their allies and the operation put an end to the three year-long siege of the town of Bihać, a mainly Muslim-Croat town that had been hemmed in on both sides by the Bosnian and Krajina Serb armies and suffered terribly.

Then there was Srebrenica.

The town and area around Srebrenica was first captured by the Bosnian Serbs in April 1992 and retaken by the Muslims the next month. A lot of hard fighting was done in the area. The Bosnian government’s forces were led by Naser Orić (below), and used the area as a staging post for very effective and damaging attacks on the Serb forces who surrounded them, at one point enlarging the area under their control to almost 1000 square kilometres. The subsequent cruelty of the Serbs in Srebrenica is sometimes explained as revenge for the trouble Orić and his forces caused them in the area. But they never succeeded in taking back enough territory to link the area to the rest of the government-controlled area, and gradually the Serbs began to press them back into a smaller and smaller area around the town. By April 1993, when the Serbs launched a major offensive to finally take it, the town was an isolated enclave of Bosnian Muslim refugees, its population swollen to over 50,000 by those who had fled the surrounding villages and countryside.

Just as it seemed on the brink of being overrun by the Serbs, a visiting French UN General, Phillipe Morillon, visited the town at this juncture to accompany a food convoy that was being obstructed by the Serbs. Desperate to do something to avert the looming disaster (and prevented from leaving by the locals), he improvised a promise that the authority of the UN would protect the town. This pressurised/shamed his bosses New York to declare Srebrenica a ‘safe area’ on April 16 1993. A few weeks later, several other areas (including Sarajevo and Goražde) were added to the list. What did it mean? In theory, that the UN was mandated to use ‘all necessary means, including the use of force’ to protect these areas if attacked by the Serbs. In practice, it meant very little. Mladić knew the resolution was little more than words, but promised Morillon he wouldn’t attack the town if the Muslim surrendered their weapons. The UN convinced the Bosnian government to agree to the terms, although in reality the Muslim forces kept much of their weapons.

Srebrenica was ‘saved’, for the moment, but the Serbs remained ensconsed around it in complete control of access into and out of what was essentially an open air concentration camp with a few UN soldiers now keeping an eye on things for them. This state of affairs went on for almost two years, with the UN failing to successfully demilitarise the area or alleviate the suffering of the people there. The situation of the town deteriorated in the summer of 1995, as the Serbs suffered defeats elsewhere and decided to attack the ‘safe areas’, having treated the UN forces with contempt, kidnapping its soldiers, violating agreements, etc. while the UN did little or nothing, obstructed by the reluctance of the UK, France and Russia. On 11 July, the Bosnian Serb army took the town after five days of fighting. Threats of NATO air strikes came to nothing after the Serbs threatened to attack UN soldiers on the group there: poorly-equipped and poorly-led Dutch troops who had been given the more or less impossible task of ‘protecting’ Srebrenica.

The UN troops fled in the face of the Serb advance, retreating to the Dutchbat compound in Potočari just north of the town, housed in an old battery factory. Many Muslims followed them and hid out there, thinking it would provide some measure of safety. The Dutch troops, many of whom were fresh out of training school and had never seen anything resembling combat, were far too few and poorly equipped to offer any kind of protection. They attract much blame and anger for simply standing by and watching as the Serbs began to round up the men and boys and separate them from the women and girls, many of whom were allowed to leave the enclave on crowded buses. This is not before many women were raped, children killed in front of their parents, parents killed in front of their children, and then, in the days following, over 8000 of the men and boys were executed in cold blood and buried in mass graves. This horror show was subsequently ruled to be an act of genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice.

Its more immediate consequences were that it contributed to jolting the French and British into finally assenting to serious air strikes on Serb positions. Many of those who had been against against action had obviously been hoping for a Serb victory, transfers of population with as little bloodshed as possible, all of which would make the work of redrawing the regions borders as straightforward as possible in the aftermath. But now it was becoming evident that the Serbs were not merely removing Muslims from parts of eastern Bosnia to other areas, but actually killing them en masse. Yet another shelling of Markale market on 28 August 1995 (this time killing forty-three people) was the final straw. The airstrikes on Serb military positions and infrastructure were the work of NATO, so the Russian veto on the UN Security council wasn’t able to prevent them. The Bosnian Serbs did not capitulate immediately; indeed they fired back at NATO’s warplanes and downed a French jet.

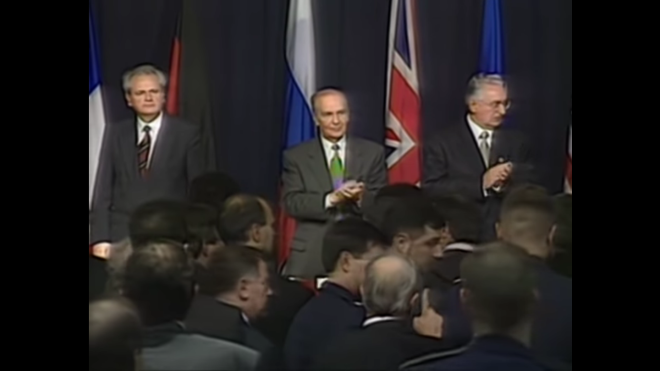

After a week of bombing, however, they agreed to withdraw their heavy artillery from the exclusion zones and by the 26 September, a real breakthrough had been made when Milošević summoned Karadžić to Belgrade and demanded that he sign a document authorising the Yugoslav president to enter peace negotiations on the Bosnian Serbs’ behalf. If he refused, Milošević made clear, he would abandon the Bosnian Serbs and cut off all aid to them, guaranteeing their rapid defeat by the Muslims and Croats. Karadžić signed, and an agreement to proceed with comprehensive peace negotiations was reached. These negotiations began at an air force base near the American city of Dayton, Ohio on 1 November 1995.

Three weeks of hard talking followed as the presidents of the three countries involved in the conflict hashed out the internal boundaries of a new Bosnian state that would include two ‘entities’ with a great deal of autonomy from one another: the the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with mostly Muslims and Croats, and the Republika Srpska, where mostly Serbs would live and run most of their own affairs. Sacrifices were made on all sides. The Serbs were forced to accept they wouldn’t get part of Sarajevo, and conceded a corridor of territory linking that city with Goražde. The Muslims had to leave Srebrenica and other enclaves in which they had been in a majority inside the borders of the Republika Srpska. The Croats, meanwhile, had to give up a considerable amount of territory they had recently taken from Serb forces. The end result was the territorial division seen in the map in the post before last. Notwithstanding many such painful decisions, the Dayton Peace Agreement was signed on 21 November 1995, with the final ratification taking place on 14 December 1995 in Paris, formally creating a new Bosnian state. Although many of the underlying tensions which led to war remain unresolved to this day, the peace established at Dayton has lasted to this day.

One much-cited claim that remains to be addressed is the idea that Bosnia became, during the war and after it, a hotbed of radical fundamentalist Islam close to the heart of Europe. In a way, this sounds plausible enough. After all, places like Algeria and Cechnia were kicking off at the same time. Afghanistan’s war against the USSR had just ended, supposedly sending out a wave of experienced jihadists around the world to put their newly-obtained military skills in the service of global conquest. In a previous post, we have already looked at some of the things these foreign fighters in Afghanistan got up to when the war against the Russians was over. One of the things we saw was that it wasn’t that straightforward. Many of those who fought in Afghanistan were not fighting a war to spread Islam, but a defensive battle against an army occupying a Muslim land. Others were more interested in taking the fight to their own secular and often-corrupt governments back home in places like Egypt and Algeria, and had less interest in taking the fight to the ‘distant enemy’ that patronised such governments (i.e. the US and the west in general).

If this blog has shown one thing so far, it is that many of the conflicts in the 1990s and after, which fantasists have attempted to fit into a narrative framework of a ‘clash of civilisations’ between the west and Islam, were in fact discrete national struggles with specific political and economic roots, which only some of those involved have tried to interpret as a ‘holy war’. For those who fought on the Bosnian government’s side (not all of whom were Muslims) this was a national struggle for survival against a Serb enemy that insisted on presenting the struggle in terms of Christian Serbs against bloodthirsty Islamic fundamentalists. This was propaganda. As we have already seen, most Bosnians were Muslim in ethnicity only, even those who might be described as ‘believers’ were of the moderate kind who wanted to build a modern secular state rather than an Islamic theocracy.

Nevertheless, the cause of Bosnia attracted some fighters from abroad who chose to view it through the prism of Islam versus Christianity. The neat narrative of global jihad has these spilling out from Afghanistan in their droves, ready to make Bosnia the next Afghanistan. Researchers who have looked closely at the type of Muslims who volunteered for the Bosnian government, however, have found that this wasn’t true and that the bulk were in fact Muslims already in Europe, many migrants from North Africa living in nearby Italy, who had seen at first hand the refugees arriving and heard their stories of suffering at Serb hands. A significant number of others were from Arab countries who had come to Yugoslavia as part of co-operation under the umbrella of the Non-Aligned Movement. (Li 2011) Many of these, while no doubt partly motivated by religious zeal, were also driven by humanitarian concerns and a desire to help their fellow Muslims rather than bringing jihad to Bosnia.

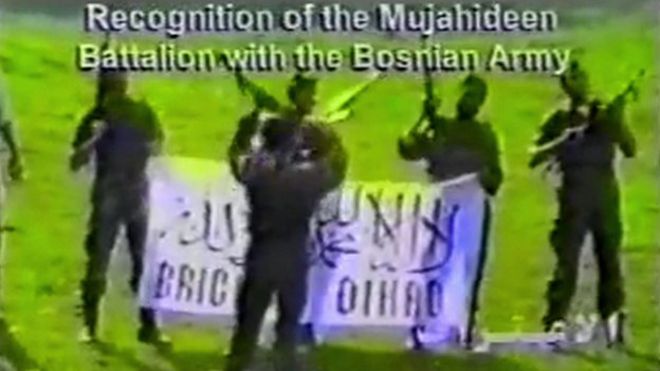

The image of crazed fanatics baying for Christian blood should, therefore, be tempered by facts. Their numbers are the subject of wild speculation, but they probably numbered somewhere between a 1000 and 2000. To put that in proportion, the Bosnian army’s total forces numbered around 110,000. There was a level of discipline among these foreign volunteers that belies the crazy jihadist image as well; in 1993 they were organised into a distinct unit called El Mudžahid under the auspices of the Bosnian state army. Although the ARBiH at times had trouble maintaining control over El Mudžahid, at the end of the war they disbanded peacefully at the request of the government. Of course, some of its members did their best to live up to the fanatic image. In the early phase of the war before their incorporation into the state army, groups of fundamentalists were active in taking over mosques, attempting to impose sharia law on locals; the area around Zeneca, a working class city north of Sarajevo became the focus of a group of around 200 Islamists who became particularly unruly and aggressive, setting up Qur’anic schools and bullying local clerics and women into adopting the veil.

This group turned its attentions to the local Croat population with the outbreak of hostilities between Muslim and Croat, and were involved in the massacre of 35 civilians at the village of Uzdol in September 1993. Perhaps more telling is the events that followed the capture of the Franciscan monastery and church in the village of Guča Gora, 15km west of Zenica. The mujahideen initially took the church and began vandalising and destroying its interior. They were stopped, however, by the regular Bosnian army commander when he arrived on the scene, and he threatened to attack them if they carried out their plan to blow the church up. The church was protected by the Bosnian army and while reports of its destruction circulated widely (used for propaganda purposes by the Croats and reported in western media) in fact local Muslims undertook to clean up the the graffiti and repair the damage under the supervision of Catholic clergy. (Walasek 2016, 135)

Notwithstanding these frightening, headline-catching and often exaggerated episodes, Islamic fundamentalism as a part of the Bosnian war was something of a damp squib. The actions of the mujahideen alienated locals for the most part, who had little interest in their puritanical brand of Islam. Early excesses led to the aforementioned formation of the foreign fighters’ unit under army control, being celebrated in the picture above. (Sadowski 1995, 12) As the atrocities during the war mounted, foreign observers predicted that Islamic fundamentalism would be fueled by the wrongs done Bosnia’s Muslims and was certain to grow, but this simply didn’t happen. The number of jihadist fighters remained relatively insignificant and the part they played in the war little more than a footnote. Enver Hadžihasanović, one of the Bosnian army’s top commanders, remarked in a BBC interview:

Mujahideen who came here to fight, in my opinion, had their own objectives and didn’t help Bosnia at all. On the contrary, I think they did Bosnia a disservice, because Bosnia didn’t need people, Bosnia needed weapons and ammunition. The army of Bosnia and Herzegovina had a sufficient number of people to fight that war.

(BBC documentary Our World: Bosnia, The Cradle of Modern Jihad? 2015)

As Hadžihasanović noted, what Bosnia really lacked was weapons, and it is perhaps in this respect—with their wallets—that the international Muslim community made more of a decisive intervention in the war. Even before the arms embargo was lifted, countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran and Turkey were helping ship arms into Bosnia for the Muslim side, but even then this support was kept low key, the Muslim countries realising that any overt influence on the conflict from their part would simply give credence to Serbian propaganda about the conflict being something to do with Christianity against Islam.

In the present day (2020) it continues to be claimed by right-wing leaders in eastern Europe, and believed by American military analysts, that radical Islam has taken root to a dangerous extent in Bosnia. There is little evidence for this. For example, the country exported 200-300 fighters to the wars in Syria and Iraq which, while higher than the European average proportional to population (not susprisingly, given its large Muslim population) is paltry compared to the numbers of jihadists from France or the UK. There have a been a few minor attacks by Islamists on police and soldiers over the years, but small in scale and nowhere near the carnage unleashed, for example, in 2015-16 in France.

As noted above, the Dayton agreement still holds in 2020. This is not to say that Bosnia and Herzegovina is now a nation without problems. In many ways, the ethnic divisions set in stone at Dayton have, while preserving peace, led to a sense of paralysis and stagnation, as the legacy of the war weighs down efforts to develop the economy and society. The concerns of the generation who fought the war continue to outweigh the interests and concerns of the younger generation who don’t remember it, who continue to suffer high unemployment and limited prospects. Emigration is reaching crisis levels, with almost half the country’s population reported to be living abroad. Interestingly, widespread protests in 2014 against the status quo reportedly saw protesters for economic justice carrying the Bosnian, Croat and Serb flag side by side, explicitly rejecting the attempt to nationalist political elites to sow division in their ranks. How significant this is will have to wait for another day, another post in the future, when I hope to examine the fate of Bosnia’s Muslim in the years after the war. But for now we will leave Bosnia to lick its wounds and backtrack in the next post to what will be both precursor and denouement of the Yugoslav crisis: events in Kosovo after the Serbs crushed its autonomy and, ten years later, precipitated the intervention of NATO by their actions there.

FURTHER READING/LISTENING/WATCHING

Leslie Benson, Yugoslavia : a concise history (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Steven Burg and Paul Shoup, The war in Bosnia-Herzegovina : ethnic conflict and international intervention (New York: Armonk, 1999)

Alex Cruikshanks’ History of Yugoslavia podcast.

John Lampe, Yugoslavia as history : twice there was a country (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Darryl Li, ‘“Afghan Arabs,” Real and Imagined,’ Middle East Report 260 (2011) https://merip.org/2011/08/afghan-arabs-real-and-imagined/

Viktor Meier, Yugoslavia : a history of its demise (London : Routledge, 2014)

Mark Pinson (ed.), The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina : their historic development from the Middle Ages to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, (Harvard University Press, 1996)

Sabrina Ramet, The Disintegration of Yugoslavia from the Death of Tito to the Fall of Milosevic, Fourth Edition, (Boulder, Colorade : Routledge, 2018)

Yahya M. Sadowski, ‘Bosnia’s Muslims: A Fundamentalist Threat?’ The Brookings Review, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Winter, 1995), pp. 10-15.

Helen Walasek (ed.), Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage (London: Routledge, 2016)

The Death of Yugoslavia (BBC documentary series first broadcast in 1995). Note the same filmmakers produced a series called The Fall of Milosevic. Just my opinion, but the latter was nowhere close to the standard of the former (excellent) series. It is far too uncritically accepting of the west’s acting in good faith in the Kosovo War and completely overlooks the possibility that there may have been ulterior motives and realpolitik at play.

Featured image above: Belongings of the inhabitants of Srebrenica lay strewn across the street a week after its seizure by Serb forces, 16 July 1995.