As I often seem to find myself doing, I will begin this post by justifying beginning so far back in the past, given that this is supposed to be a ‘contemporary’ history, and that what I am ultimately interested in exploring here is the Algerian Civil War of the 1990s and the growth and nature of the Islamist movement there. There is no way of understanding what went wrong in Algeria at this time, however, without understanding its bitter and traumatic struggle for independence from France, and there is no way of understanding that struggle without looking at what French rule actually meant in practice. It isn’t a huge leap from examining the conquest by France in 1830, to looking back at the period of Ottoman rule and the very beginnings of a concept of something called Algeria, as a distinct region in the central Maghreb. So, back to the sixteenth century it is, and the fallout of the Spanish conquest over the last Muslim stronghold in Iberia, Grenada, in 1492.

Emboldened by its expulsion of the Muslims from Iberia (at the same time their ships were landing in America for the first time) the Spanish invaded North Africa in the years that followed, and the fragmented dynasties that ruled small territories in the region appealed to the Ottomans (a major power at the time, having conquered Constantinople/Istanbul in 1453) for help. There followed a period in which the Spanish and Ottoman Turks vied for power in the region, some local dynasties siding with one of the other power, embroiled as they were in their own power struggles with each other. By 1529, a group of Ottoman adventurers had succeeded in establishing a unified state from these disparate territories with its capital at a small port town called Jaza’ir Bani Mazghana, or as it is today known, Algiers, which gave its name to this new state, the Eyalet or Regency of Algiers, a vassal state ruled immediately by figures (who held titles like Dey, Pasha, Agha) who were ultimately subordinate to the Sultan back in Turkey. The Ottomans survived a serious attempt to retake Algiers in 1541, led by the Habsburg emperor Charles V, and ruled the area for the following three centuries, during which the idea of a (sort of) cohesive territory known as ‘Algeria’ began to be distinguished from the surrounding area (modern-day Morocco to the west and Tunisia-Libya to the east).

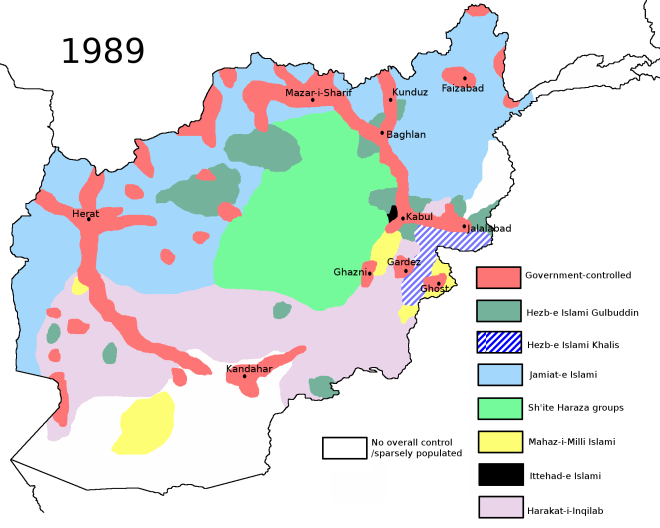

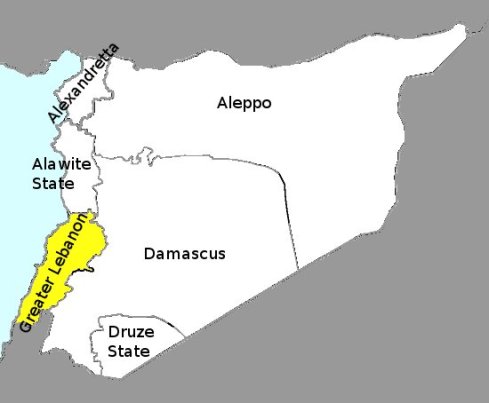

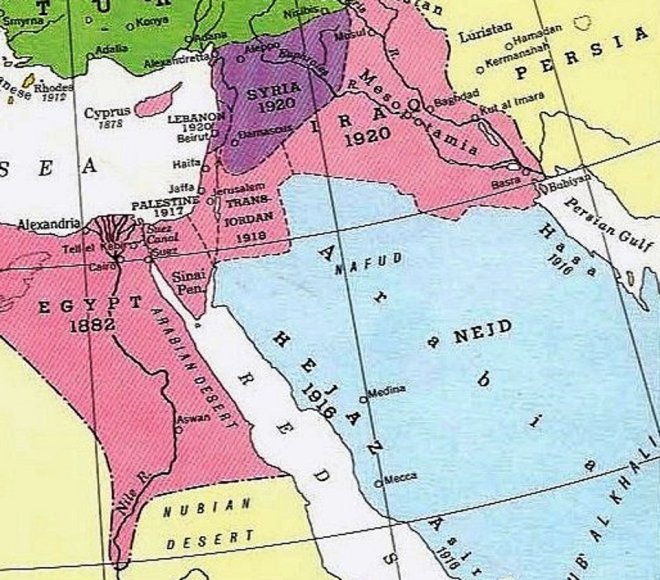

As we want to get to the twentieth century as quickly as possible rather than get bogged down in the detail of Ottoman rule (although interesting in its own right) we are going to gloss over these centuries, noting a couple of points on the way: firstly, the regents who ruled Algeria on behalf of the Ottoman empire enjoyed a great deal of autonomy, especially after the advent of a class of rulers known as the dey in 1671, so much so that they often conducted their own foreign policy, having independent diplomatic relations with many European powers. In this sense, Algeria then might be considered what we now call an independent state, even while nominally a part of the Ottoman empire. This does not mean that it enjoyed self-determination, however. While they shared the same Islamic religion as their subjects, the Ottomans were foreign rulers, and they failed to cultivate an indigenous ruling class. The country was ruled by a Turkish military corps and privateering entrepreneurs, mostly outsiders, while the native population’s main contact with the administration was through judges and tax collectors whose role was to manipulate and control the local tribes and their leaders. A dichotomy in Algeria between the mountains and the plains (see map below) is important.

In the lowland areas, looking out over or at least in contact with the coast, lived a people who not only interacted with whatever foreign power happened to be running the country at the time, but interacted with the broader Mediterranean world as a whole. The mountains, on the other hand, were beyond the control of the state and inhabited by independent peoples who were never under anything more than a loose, distant rule. They maintained their tradition of resistance to central authority, whether it be that of the Ottomans, the French, or later on the Algerian government itself. This divide can also be loosely seen in terms of the Arab plains and the Berber mountains. Although its ruling elite have sometimes forgotten it, Algeria is not an exclusively-Arab country. The Berbers lived here before the Arabs settled the area in the centuries after its conquest by the Muslim Caliphate in the seventh century, and to this day they constitute somewhere between 25-30% of the population, speaking their own language, Tamazight, and concentrated in the Kabylie region east of Algiers.

The name Berber has the same origins as the term ‘barbarian’, from the Greek word barbaroi, which they used to describe anyone who didn’t speak Greek. For some reason, it stuck as the ethnic identifier of the Berber people of North Africa, and also gave the name ‘Barbary coast’ to the area, as well as ‘Barbary pirates’ which was what this area of North Africa was primarily known for in Europe in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, when pirates known as corsairs operated with the blessing of the Ottoman regents, kidnapping people and selling them into slavery, or making money by ransoming them back to their European rulers (the ones who were prepared to pay for them anyway). The heyday of the Barbary corsairs had passed by 1830, when the country was conquered by France, although there was a recrudescence of activity in the period of European instability accompanying the Napoleonic wars. It was in this context that the French invaded Algeria in the last days of the restored Bourbon monarchy.

Very very briefly, the French Revolution developed into the military dictatorship of Napoleon Bonaparte, who founded the first French empire. On its defeat by the Seventh Coalition at Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon was finally deposed for good and the Bourbon monarchy, which had been abolished by the original Revolution in 1792, was restored. By 1830, the highly-conservative Charles X was deeply unpopular at home and (classic example of a troubled regime trying to bolster its popularity by launching an unnecessary foreign war) took advantage of a diplomatic incident in which the Algerian dey hit the French consul with a fly whisk while demanding the French pay a very large, and very late loan. In response, the French king blockaded Algiers for three years and, when a French ship was bombarded, decided to launch an invasion in June 1830. The Ottoman (not very robust) defenses were subdued and Algiers taken on 7 July, although the Bourbon dynasty that had launched the war lasted less than a month after this, as the July Revolution of 26–29 saw Charles X deposed and replaced by the Orléanist Louis Philippe, who would rule for eighteen years until France once again became a republic (the second) in 1848.

The Ottoman’s attempt to retain their hold over Algeria may have been swatted aside relatively quickly by the French (who quickly found a new commander prepared to swear allegiance to the new king), but the Algerian’s resistance to the French invasion took decades to quell. This was led in the eastern half of the country by a religious-military leader called Emir Abdelkader, who succeeded in holding the French at bay in the east for over a decade, until forced to surrender in 1847, whereupon the French (who had promised to let him leave the country and settle abroad) imprisoned him in France. Abdelkader is a fascinating figure to whom I can’t do justice in the limited space here. Renowned for his relatively-enlightened views on human rights and his honourable treatment of enemy prisoners, he later gained even more admiration, even in the west, for his protection of Christians in Damascus, having been released by the French and allowed to settle there. He underwent a transformation in the French imagination, from rebellious fanatic to honourable enemy. They even built statues of him in the 1940s.

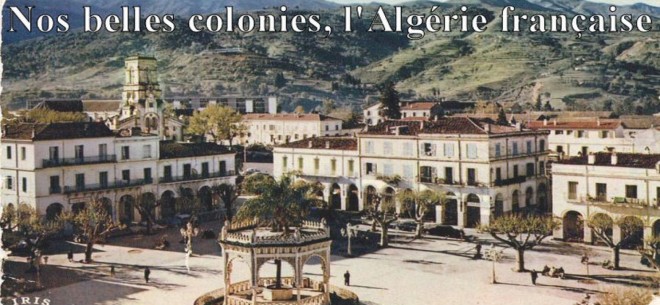

Having consolidated their hold over the country, the French were in for the long haul. What Algeria endured under French rule was far more thoroughgoing and invasive a conquest than that experienced by most other French colonies. As a writer who is primarily concerned with Irish history of the seventeenth century, I cannot help being struck by the many parallels between Algeria’s ordeal under French rule and Ireland’s with English. For one thing, Algeria became a settler colony just over the water and not merely one in which a distant government exploited a subject population for material gain. French people (often poorer people squeezed out of the home economy or those seeking cheap or practically free land) emigrated across the Mediterranean in large numbers and, at their peak in 1926, came to comprise 15% of the population. The French even denied Algeria was a colony (just as some continue to deny Ireland was) by legally integrating the country (the northern part at least) into France as three départements (Alger, Oran, and Constantine) after the 1848 revolution. This was something which the French settlers liked to imagine made them as French as Paris or Nice. Indeed the latter was only a part of France since 1860.

The Pieds-Noirs (the name given to people of European descent who were born there and came to constitute the ruling class) actually ruled over the Arab-Berber Muslims as conquerors over a conquered people. The reality of life for this subject people belies the idea that it was ever ‘just another part of France’. Such a notion is patently nonsense, and again I am reminded of Margaret Thatcher’s equally-nonsensical statement that Northern Ireland (basically a war-zone at the time) was ‘as British as Finchley’. So let’s look at what made Algeria a colony in fact, if not on paper. It goes a lot of the way to explaining why most Algerians would come to emphatically reject French rule.

A caveat, and a revealing one at that, should be noted here: that not all Algerians explicitly rejected French rule from the word go, and for a long time some of them believed it might be turned to their favour. There are reasons for suspecting that many of these might have accepted it if they had actually been treated as equals and not subjected to the abuse and depredations of the Pieds-Noirs. Such an idea, that the modernisation and development of Algeria might take place under the aegis of French rule if only the natives were admitted to the same rights and privileges as the colonists, can be detected in the early thought of someone like Ferhat Abbas, who would later become a separatist but who in his earlier years had campaigned for equal rights for Muslims under French rule. It was only when the racist underpinnings of that rule became apparent did people like Abbas realise that this was never going to happen.

And this racism is crucial to recognise: the belief on the part of the Europeans that the native people were simply worth less and that the values that regulate human society in Europe did not operate there. This remained the case right up until the end of French rule and was in evidence from the very start, in the conduct of the war of conquest, where promises of respect for rights and the Algerians’ culture and religion were violated almost immediately, as people were summarily executed by an army completely without discipline and restraint, entire tribes were wiped out (the Ouffia, for example, who were all killed as punishment for the theft of some cattle) and one of Algiers’ main mosques confiscated and converted into a cathedral. As a commission of inquiry appointed by the French themselves put it:

We have sent to the gallows, on the merest suspicion and without trial, people whose guilt has remained more than doubtful, and whose heirs have since been despoiled of their goods; we have killed people carrying promises of safe-conduct, massacred on suspicion whole populations who were afterwards proven innocent [. . .] we have outdone in barbarism the barbarians whom we came to civilise and we complain of not having been able to succeed in civilising them.

Commission nominated by the king, 7 July 1833

Despite the enlightened sentiments here, note at the end the belief that the French had come to ‘civilise’ Algeria. Notwithstanding all the brutality and evidence to the contrary, those liberal Europeans (this is not a uniquely French thing) continued (and continue) to labour under the delusion that their colonial project was motivated by essentially noble intentions of spreading ‘liberty’ and ‘progress’ among ‘backward’ peoples, a cause betrayed by a few wayward generals and greedy landgrabbers. This idea would prove, in its way, more pernicious than the wayward generals and greedy landgrabbers, in that it has allowed France (and Britain) to tell itself a story of its empire completely at odds with the evidence: that the colonies were, in fact, an expression of the will of the aforementioned worst elements in their societies and were all about exploiting subject peoples overseas in the economic interest of the ‘mother country’. The liberal rhetoric was merely window-dressing, and not even window-dressing that was very prominent at the time. While toothless commissions may have condemned the conduct of the conquest and occupation, its commander spoke before the National Assembly in 1840 with refreshing candour:

Wherever there is fresh water and fertile land, there one must locate colonizers, without concerning oneself to whom these lands belong.

Thomas-Robert Bugeaud

And so it was. Algeria became known as a place where poor French people could come and get their hands on land for next to nothing. This land had to come from somewhere or, to be more specific, someone, and that someone was of course the native Algerians.

Some continue to claim that the transformation of the Algerian population to the point that they would become fully integrated into the French nation was a sincere (if long-term) goal of French rule. It bears taking a closer look, therefore, at some of the evidence that this was empty rhetoric, basing our assessment on the actual actions (as opposed to professed intentions) of those who ran Algeria: the settlers who, with the full backing of Paris, sought to keep the native population in subjugation. One hint that the integration of the Algerians into French society was not envisaged is that laws enacted in 1865 stipulated that Muslims were to be subject to Islamic law and Muslim judges (the cadis) as opposed to the French civil code, which sounds very tolerant and relativistic, but does give the lie to the idea that the French were interested in reforming the Muslims’ culture and legal system. Furthermore, it meant that, if a Muslim wanted to become a French citizen and enjoy all the attendant rights, they had to sign away their right to be governed by their own laws, essentially abandoning their religion. Given that religion is tied up with culture and values in such a complex way, it is not surprising that few Algerians made this choice. By 1936 only 2,500 had done this. (Evans and Phillips, 2007)

As an ‘integral part of France’, Algeria sent six deputies to the Assemblée nationale in Paris. But only French citizens could vote, so this effectively disenfranchised almost all natives. The government elected by the Pieds-Noirs served their interests exclusively, and because they perceived their interests to be threatened by any concessions towards the Arab and Berbers, Algeria’s ‘representatives’ worked hard to defeat any measures that might be cooked up in Paris to make life easier for the Algerians. Discrimination was hardwired into the system. Three departmental councils were established in 1875, on which colonists were guaranteed four-fifths of the seats, despite constituting little more than a tenth of the population. The fifth of seats allocated to Muslims were, in any case, handpicked by the French authorities. At a local government level, the percentage of Muslim representatives could not exceed one quarter. In communes mixtes, places where there were basically no Europeans yet, all representatives were appointed by the French administration. While Muslims were subject to Islamic law in some cases, there was also a special set of French laws enacted in 1881, the Code de l’Indigénat, which imposed harsh penalties for ‘crimes’ such as being rude to a colonial official or making disrespectful remarks about the Third Republic. On a day-to-day basis the supposed racial superiority of the Pieds-Noirs was reinforced. Settlers addressed all Muslims by the familiar tu rather than the more respectful vous, by which they insisted the natives address them. Algerians were regularly referred to by racial slurs such as melon, raton and bougnoule (the equivalent of terms like ‘raghead’ or ‘wog’ in English) or addressed by settlers as if they were children, which is reminiscent of the way blacks in Apartheid South Africa or the antebellum south were often addressed as ‘boy’, even by young people addressing elderly men.

Another idea that should be addressed is the claim (which continues to be bandied about by apologists) that French rule, even if harsh, raised the material living standards of the natives and, as such, was somehow a blessing for all its flaws. The facts simply do not bear this out. Economically, the communes arranged their finances for the exclusive benefit of the French settlers and taxed the natives as they saw fit. Even an imperial fan-boy like Jules Ferry described the system as ‘daylight robbery’. (Ageron, 1991) The Warnier law of 1873 was particularly destructive in that destroyed indigenous, communally-owned landowning practices, allowing smaller parcels to be bought up by settlers. And boy did they buy land, in the following three decades acquiring almost one million hectares. (Evans and Phillips, 2007) As more and more land was taken from them, the natives were crammed into the cities or emigrated to France, that is to say, the native population were impoverished by colonisation, with the exception of a small elite of collaborators.

Their growing immiseration was accompanied by a rapid population growth in the century that followed the French conquest, tripling to reach 6.5 million by 1940. This growth was largely a result of French medical science reducing child mortality, which might be placed in the ‘progress’ column, but for the fact that this growth came during a period when Algerians were less and less able to feed all these new mouths. The results were predictably catastrophic. A famine in 1867 cost untold thousands of lives (I have read conservative estimates of 800,000: McDougall, 2017) while as late as 1937, a terrible famine (for which I can find no solid casualty figures) saw corpses litter the roadsides while the colonists suffered few shortages. Again, this was because during times of economic contraction (like the 1930s Depression), the Algerian government was wholly focused on protecting the settlers’ economic interests above all else. Some cheerleaders for French rule have argued that the number of casualties in these famines was a result of the backwardness of native agriculture, and actually spoke for the imperative of French agricultural ‘modernisation’. In fact, Algerian society had, through centuries-long experience of surviving in an environment that permitted only a marginal existence, developed their own techniques, such as storing a certain amount of food for times of hardship, to handle such crises. Life in such harsh environments has to be rigorously disciplined and organised to make the best of scarce resources and the people actually living there knew best how to do so. When the French came in with their land confiscations, the impoverishment of the rural population messed up this system, pushing them to the point where food scarcity resulted in starvation and death. (Evans and Phillips, 2007)

So much for progress.

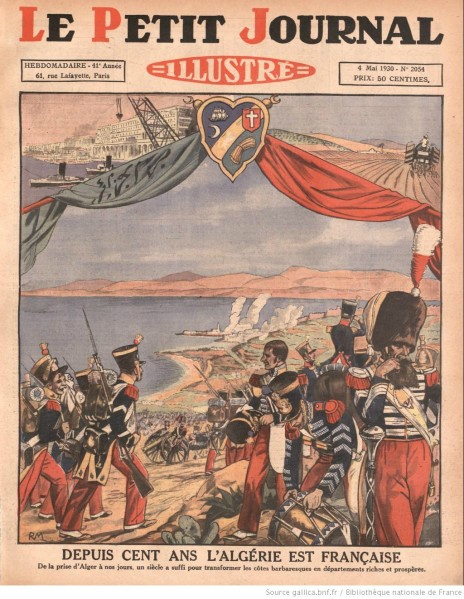

In 1930, the French establishment celebrated a century of this misery with much aplomb and rhetoric about the benefits of their ‘civilising mission’. The following magazine cover gives you some idea of the vibe. The subtitle beneath the headline reads: ‘Since the capture of Algiers, a century has sufficed to transform the barbarian coast into rich and prosperous departments’.

The Algerians, it would become increasingly apparent in the following decades, did not feel the same way.

The turn of the twentieth century might be mistaken for a period of ‘peace’ in French Algeria, as overt organised resistance from the population subsided. This has more to do with the utter subjection of the people than their contentment, however, as James McDougall has described this gap up until the beginnings of the independence struggle in the 1950s:

…the ‘law and order’ that followed, and with which Algerians thereafter had to contend, remained [. . .] a life lived under conditions of continuous, low-intensity warfare’.

McDougall, A history of Algeria

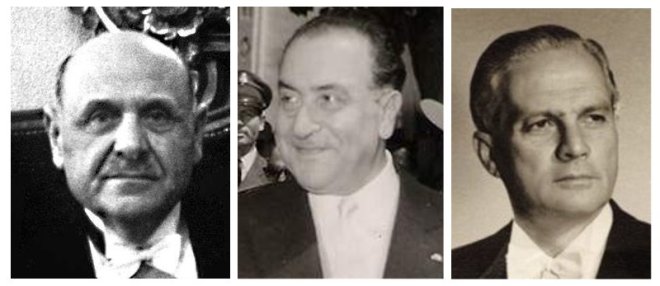

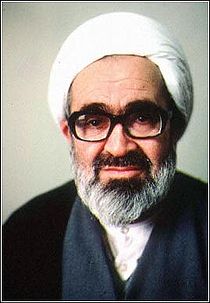

Even the beginnings of political activity in the Algerians’ interest cannot be rightly considered a nationalist or separatist movement from the start. As indicated above, people like Ferhat Abbas (below) initially saw the struggle of the Algerian people in terms of winning rights under French rule, not outside it. He even denied, as late as 1936, the existence of any notion of Algeria as a nation. Remember, this was the same dude who would become the nation’s first president thirty years later. Other groups, such as the jeunes Algériens or ‘Young Algerians’ of the 1910s likewise presented their demands in terms of increased civil rights and assimilation for Arabs and Berbers within French society, not separation. Things began to change, however, in the period around World War Two, as Algerians’ calls for their rights grew louder, and it became more and more clear the French would never grant them.

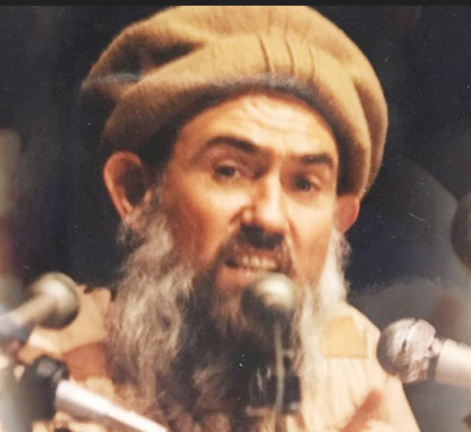

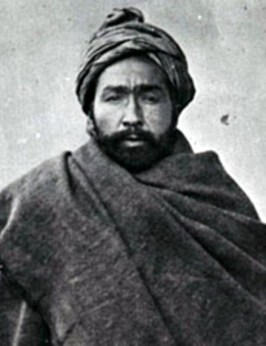

In 1936, a left-wing, anti-fascist government was elected in France, the Popular Front, which was relatively enlightened and progressive by the standards of its time and attempted to introduce some modest reforms which would have given citizenship to some Algerians. Seeing any conciliation towards the Muslims as the beginning of Armageddon, the Pieds-Noirs bitterly opposed these and they never got off the drawing board. Things might have been different if these reforms had succeeded, but after this failure, it became difficult to argue for anything other than complete independence on the Algerian side; indeed, the reforms were opposed by an emerging separatist movement led by Messali Hadj (below), often considered the grandfather of the independence movement.

Of humble origins and a self-taught intellectual and scholar, Hadj was an electrifying public speaker who had spent time in France, influenced both by the Communists and, increasingly, a sense of Islamic nationalism which placed religion at the heart of Algeria’s struggle for separation from France and a recovery of its honour. From the 1920s onwards he spent long bouts in prison, even being deported to the Congo by the Fascist Vichy government during World War Two. The Vichy regime was of course brutally repressive, although popular with the Pieds-Noirs, and besides a campaign of zero tolerance towards the separatist movement that was emerging, they also revoked the citizenship of the Jews in Algeria, who would henceforth be treated as second-class citizens, just like the Muslims.

The Second World War, and the ‘liberation’ of Algeria from Vichy (although the applicability of the term ‘liberation’ must be questioned, given that it simply returned to the colonial fold of ‘Free’ France), was nevertheless a watershed for the independence movement. Although leaders like Churchill and De Gaulle tried to argue that the principles of self-determination, enshrined in the Atlantic and later the United Nations charters, only applied to European countries, Arabs, Vietnamese and other peoples saw no reason why they should not apply to them as well. Agitation for independence or at least autonomy had been brewing for some time, but the impulse was quickened by several factors and events. Firstly, there was no doubt the huge participation of Muslim soldiers in the French war effort. Just like many other colonies in both world wars, many indigenous people fought for their colonial masters in expectation that their sacrifice would be rewarded by being treated as equals within the empire. Muslims made up 90% of the ‘French’ force defending Algeria. In a desperately poor country, the army was a steady job and many young men were attracted to what, under the circumstances, was a relatively secure income for themselves and, if they got killed, those family members they left behind. In this respect, Algeria was like Ireland during World War One, where many Irishmen volunteered for the British army and, despite attempts by some to claim that this suggests loyalty and affection for the ruling power, it is far more likely that there weren’t many other jobs available for men, who were left with little choice but to join the army.

The fact that such a large proportion of the army defending Algeria was Muslim begged the question: were they simply holding the fort until the colonial power was able to resume power? After the allies removed the Vichy regime from North Africa and returned the colony to De Gaulle’s government in 1942, there was hope among Algerian separatists that the defeat of German fascism might be linked with the fight against French fascism. An umbrella-organisation of most progressive Algerian parties, the Association des Amis du Manifeste et de la Liberté (AML) was founded and, at the end of the war, on VE Day itself (8 May 1945), demonstrations were organised throughout the country to remind the French that the end of the war did not mean a return to business as usual. Unfortunately, as far as the Pieds-Noirs were concerned, this was exactly what it meant. Most demos passed off peacefully, but at Sétif (see map for locations) in the east of the country, one group was attacked by the police, in retaliation for which the demonstrators began to indiscriminately attack the settler population, killing around 100 people. In counter-retaliation for this, the authorities launched brutal revenge attacks that left between 6,000 and 20,000 dead (yes, those figures are vague, because they are hotly debated, but in any case, it was a lot) and the violence spread to other areas, especially Guelma, where the army carried out mass executions and pretty much all Arab males were considered fair game.

This was a turning point. The AML and other organisations agitating for separatism were dissolved and banned. Even moderate leaders like Abbas were imprisoned and the army given a free hand to crush the movement by violence. Many of those responsible for this repression were the leaders of La Résistance, supposedly the more progressive elements of French political society such as the French Communist Party, who rather absurdly blamed Nazi Germany (who had just been defeated) for organising the protests. It was becoming clear to Algerians that even the left in France was indoctrinated to believe their rule was justified and would never take concrete action towards even modest reforms. This realisation created a new generation of separatists who would fight for nothing less than complete independence, and more radical parties and even armed cells began to form, especially in remote areas where they were harder to keep an eye on. Those reformists who sought to work within the parameters of French rule, meanwhile, became irrelevant, even as modest reforms were carried out, which to most Algerians were too little too late, and to most Pieds-Noir were a step too far.

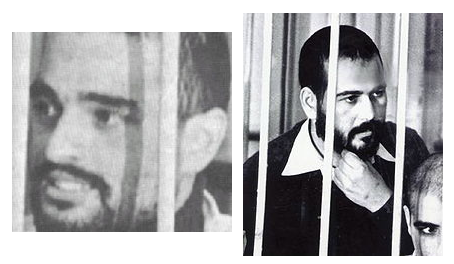

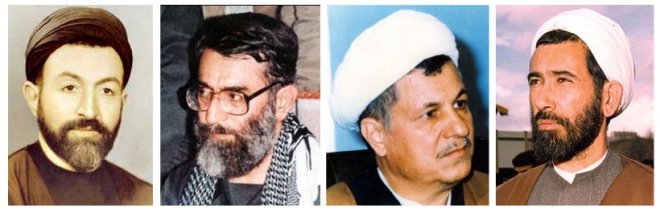

The first manifestation of a new movement devoted to armed struggle was the Organisation Spéciale (OS), a secret guerilla group that was linked to Messali’s political movement. Several of the key figures in the Algerian War of Independence first made a name for themselves in the OS: Ahmed Ben Bella, Mohamed Boudiaf and Hocine Aït Ahmed, pictured here (left to right) under arrest together in 1956:

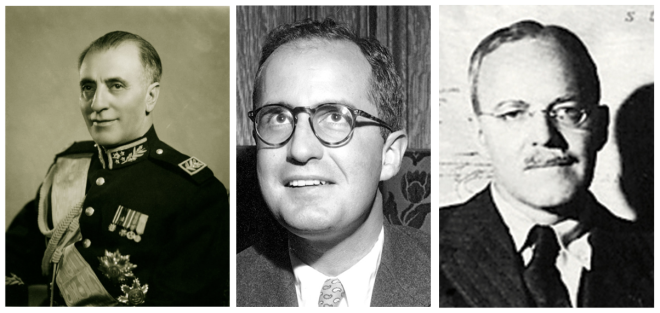

The military activities of the OS simply provoked the French authorities to redouble the repression, and the movement was decimated by arrests and confiscation of their weapons in the years that followed. Ben Bella was arrested but escaped to Egypt, while other leaders had to go into hiding. The momentum seemed lost at that point, and in October 1954, the minister of the interior (later president from 1981-95) François Mitterrand toured the country (pictured on the right, below), sending out a clear message that, although his government had already lost the northern part of its Indochina colony to Hồ Chí Minh’s Viet Minh, and was in the process of conceding independence to neighbouring Morocco and Tuniaia, Algeria would remain French and that the settlers had the government’s full support.

But unbeknownst to the French, a new body had been in existence for some months which would soon assume the name Front de libération nationale (FLN). This was another clandestine paramilitary organisation, to which most of the OS leaders became attached which, although ostensibly no better-prepared than the OS, launched a series of co-ordinated attacks against French targets only a fortnight after Mitterand’s visit. This date, 1 November, is generally regarded as the beginning of the FLN’s eight-year war against French rule which would win independence for their country. That this would be the eventual outcome was far from clear in the first years of the war, as the French turned the screw and the general uprising of the population against colonial rule which the FLN had hoped to spark off, failed to occur.

In fact, it is questionable whether some of the FLN’s more astute leaders even expected this to happen. Many of them were aware that their struggle, a few hundred poorly-armed men and women against the fourth-largest army in the world, had little prospect of military victory, but this was not the point. The strategy was instead to use armed struggle to achieve political ends by making Algeria ungovernable, by provoking the French into repressive measures that would fatally undermine the legitimacy of their rule both at home and abroad. In this, the FLN were extraordinarily successful, and the Algerian War of Independence is a classic example of an imperial power winning tactically, but failing strategically, winning the war but losing the peace. How exactly was this seemingly-impossible task achieved?

In its initial stages, FLN attacks were isolated and mainly concentrated in the countryside of central and eastern Algeria. Despite its aspirations, it did not enjoy the unequivocal support of the masses. While many no doubt shared the goal and broadly sympathised with its objectives, this does not mean they were willing to risk their lives or their families’ lives in order to help them or participate in the uprising. As ever, most people probably hedged their bets, reluctant to commit themselves to one or the other side until they saw who had the upper hand. This would be apparent in the closing months of the conflict, when it became clear the FLN had won and many so-called marsiens joined in order to gain some of the credit and show their loyalty to the new ruling party.

In the early days, however, when the French state still enjoyed overwhelming superiority, it might sound strange to say that some were obliged to hedge their bets, but this is because the FLN employed coercive methods of their own to drag an uncommitted population kicking and screaming (sometimes literally) into the revolution. As we will see in the civil war of the 1990s, neutrality or fence-sitting was simply not an option for most civilians. Non-committal to one side was considered siding with the enemy, and both the French and the FLN forced people to co-operate with them, often at gunpoint. Examples (often gruesome, such as throat-cutting) were made of those who betrayed the FLN to the authorities and refused to aid the insurgents.

A key dynamic here is that the French played their assigned role of dumb colonial oppressor to perfection. The summer of 1955 especially was a turning point, as the army enforced a policy of collective responsibility, punishing whole populations for the actions of the FLN. This backfired spectacularly, of course, and ensured the population identified with the FLN en masse in areas where they hadn’t before. In August, dozens of women and children were massacred alongside FLN fighters. As the bodies piled up, the situation became more polarised, and the idealistic rhetoric of those who sought to amend the status quo by reform became untenable. The FLN made sure this was made clear to rival political organisations by demanding their dissolution, and that they all come under their umbrella and fight together. One of the FLN’s most firmly-held tenets was the need for unity and an anxiety to avoid the factional infighting of the past. No more, they declared, would Algerian nationalists dissipate their energies by internecine quarreling. Somewhat ominously for the future of multi-party politics in Algeria, however, it is clear that they regarded multi-party politics itself as ‘internecine quarreling’ and a dissipation of vital revolutionary energy, but more of that in the next post.

Even longstanding campaigners for separatism such as Messali Hadj became branded traitors to the cause for refusing to toe the party line. The year the FLN launched their campaign, his followers formed a rival group, the Algerian National Movement (MNA: Mouvement national algérien) which became embroiled in a vicious civil war with the FLN in the following years, resulting in numerous atrocities. The MNA was particularly strong among emigré communities in France, and the two fought each other in what is often known as the ‘café wars’ in which as many as 5000 people lost their lives. While a hero to many with Alegrian nationalism, by September 1959 the FLN was attempting to assassinate Messali Hadj. Although he survived, many other prominent leaders did not, and by 1960, the MNA in Algeria was practically destroyed. While Ferhat Abbas attempted to maintain his stance as a ‘moderate’ conciliatory figure in the early stages of the war, its polarising logic led him to take a more pragmatic route, and he joined the FLN in 1956, being utilised as a diplomat and a representative on the world stage and, when the time came, a figure the French might see as someone they could negotiate with.

The growing prestige of the FLN as the sole torch-bearer of the independence struggle followed a series of diplomatic successes in 1955. They were invited to the historic Bandung Conference of newly-independent ‘Third World’ nations, and recognised as the representatives of Algeria. They also got their situation discussed at the United Nations, which provoked a walk-out by the French in protest against interference in their ‘internal affairs’. While things may have been going well on the political front, however, on the military, they were being squeezed. The actual military wing of the FLN was officially known as the ALN (Armée de libération nationale) and comprised elements within Algeria fighting both a rural and urban war, but also armed forces outside the country in Morocco and Tunisia, who allowed them to operate within their territory when they became independent in 1956. At the end of 1959, this ‘frontier army’ was formally organised under the command of a twenty-seven year-old colonel, Houari Boumediène. Both this frontier army outside the borders of Algeria (for the moment) and Boumediène himself will become crucial figures in the story of post-independence Algeria.

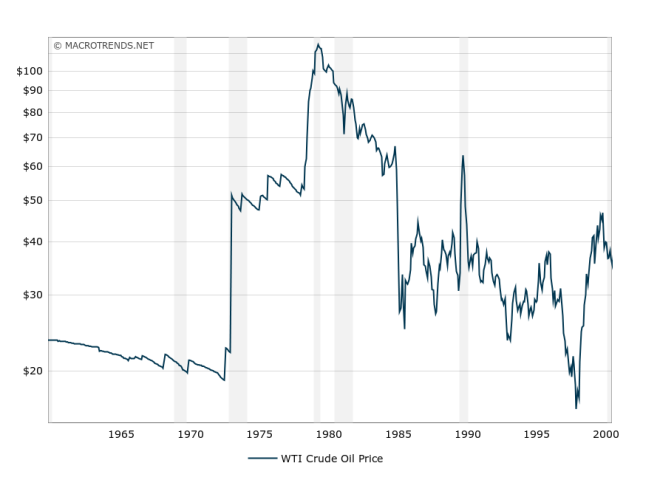

If there had been any inclination on the part of the French to compromise, this was now abandoned and they committed themselves to total victory over the FLN, although they refused to officially acknowledge it as a war (and, by extension, the FLN as a legitimate enemy) and maintained the legal fiction that the whole thing was merely a criminal problem. This renewed determination was perhaps not unrelated to the fact that they had recently discovered oil (they badly needed their own supply which they could pay for in Francs, so they were feverishly searching in the Sahara) at Hassi Messaoud in 1956. Later on, they would be so desperate to hang on to this that they offered the FLN an independent state that excluded the interior areas of desert where the oil was. For all the nationalistic bombast and talk of prestige and defending their colonists, this simple material exploitative relationship between the metropole and colony should always be remembered. Similarly, France used the Sahara to test its first nuclear devices in 1960, and continued to do so for several years after the country became independent.

Getting back to the war (oops, criminal problem), in early 1956, the French government voted ‘special powers’ to the Algerian settlers, and basically gave them a free hand to do whatever it took. Between March and July 1956 the number of French soldiers in the country doubled from around 200,000 to 400,000 (McDougall), and in October of that year Ben Bella, Boudiaf and Aït Ahmed were all abducted after they were kidnapped by the French authorities when en route between Morocco and Tunisia. In what must surely count as one of the world’s first acts of airline terrorism, the FLN leaders were scheduled to take a flight from meeting the sultan of Morocco to the Tunisian government. The airplane, which was Moroccan, was nevertheless registered in France and the pilot had a French license. While flying over Algeria, he was ordered by the military to land, whereupon Ben Bella and the others were arrested. It was a flagrantly illegal act which was initially celebrated by the French ruling elite, but only further undermined their legitimacy and made them look like a criminal gang.

The year that followed, up to around October 1957, is often described as the ‘Battle of Algiers’, as the army focused on crushing the FLN in the capital. They succeeded militarily, but the means they used to do so made a great contribution to the eventual strategic defeat of the French. By this stage, the army was more or less a law unto itself, acting outside all legal and moral norms. The paratroopers under the command of Jacques Massu (below) were particularly notorious, and a campaign of systematic torture and extra-judicial executions was carried out to break the urban guerrillas. Often this torture (which typically involved electrocution, simulated-drowning and rape) was not even to extract information, but merely to humiliate and demoralise the Algerians who, in many cases, were not even FLN activists, although you can imagine a lot of them ended up being after they were released. If they were released. Some prisoners were thrown to their death from the windows of prisons and police stations, others were brought into the forest, ostensibly to collect wood, where they were shot for ‘attempting to escape’. If the FLN member Louisette Ighilahriz is to be believed in an interview she gave in 2000 (and I don’t see why she would lie), General Massu was present at these tortures, and watched as she was raped and tortured repeatedly in 1957.

Massu, along with others like Marcel Bigeard, Raoul Salan and Maurice Challe (more of whom below) were the ones who presided over this carnage. Another well known name is that of Paul Aussaresses, who orchestrated much of the killing and torture under Massu. While others tried to play down or express mealy-mouthed regret for what happened, Aussaresses is one of those unrepentant imperialists that provide great material for a historian. Either too stupid or too racist to be ashamed of his and his colleagues’ actions, he wrote a bullish defense of French crimes, arguing that they were necessary, also revealing how these actions were not just those of a few ‘bad apples’, but sanctioned from the highest levels of government. Aussaresses could write with the assurance of knowing that De Gaulle passed an amnesty by presidential decree for all Algerian commanders in the 1960s, which meant they couldn’t be prosecuted for what they did. Even if it couldn’t form the basis for a trial, it is in any case a great source for the period. Another great source is The Battle of Algiers (1966), a fantastic film about the war, an absolute classic of the art form directed by the Italian Gillo Pontecorvo based on the memoirs of FLN soldier Saadi Yacef.

It also contains one of my favourite bits of dialogue from a film ever, at 1:28:34, when the captured FLN leader, Ben M’Hidi, is attacked by a French journalist for using bombs in baskets to kill innocent civilians:

Isn’t it cowardly to use your women’s baskets to carry bombs, which have taken so many innocent lives?

To which Ben M’Hidi replies:

And doesn’t it seem to you even more cowardly to drop napalm bombs on unarmed villages, so that there are a thousand times more innocent victims? Of course, if we had your airplanes it would be a lot easier for us. Give us your bombers, and you can have our baskets.

Larbi Ben M’Hidi, incidentally, was one of the founders of the FLN who was captured in February 1957, tortured and hung by the army, who said he committed suicide. Aussaresses in 2000 finally admitted that his men murdered him in custody. Here is a picture of him with his captors. Everyone looks oddly cheerful:

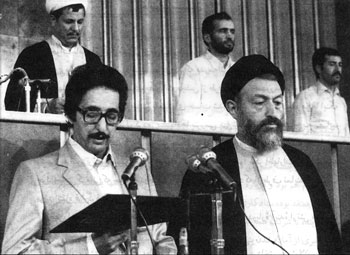

It was in military defeat that the FLN and its cause found the path to victory. With the people now not merely alienated towards the French, but prepared to risk everything to end their rule, they declared a Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) in September 1958, in exile, first in Cairo, then moved to Tunis. Abbas was its first president, although this should not mislead us into thinking he was really a leading figure in the struggle now. The post was largely an honorary one, and he was appointed mainly because of the esteem in which he was held abroad and in diplomatic circles. The new president was very much being led by events now, as opposed to leading them. Just who was leading events is hard to say. Within the FLN certainly, the military was always the prime mover, and the political elements affirmed this over and over again. Militarily, however, the FLN was almost defeated by 1958. At this point, however, French political turmoil breathed new life into the Algerian liberation struggle.

As this is a post about Algerian history, I do not want to dwell at length on French internal politics. Briefly, the Algerian situation was one of several causes of mounting discontent with the series of ineffective governments of the Fourth Republic, which suffered from, among other defects, a weak executive, and was perceived as being too indecisive to hold on to the colonies. The crisis came to a head in 1958, as rumours were rife that the government (there had been twenty-one of them since the republic’s founding just twelve years earlier) were about to enter into negotiations with the FLN. The Algerian settlers, led by General Massu, campaigned to have the retired Charles de Gaulle returned to a new, more powerful, presidency, and the army threatened a military coup if the government refused to make it happen. In May, the Fourth Republic acquiesced, voting itself out of existence and making De Gaulle ruler of what would soon be the Fifth Republic.

The Pieds-Noirs and the army generals were, of course, delighted. They had got ‘their man’ installed in power now, and surely he would soon put the boot in and finish off the independence struggle once and for all. This is what they were under the impression he had promised when he declared from the balcony of the governor-general’s residence ‘Je vous ai compris’ (I have understood you). They were, however, in for a rude awakening. Although De Gaulle had made macho statements about keeping Algeria French forever, when it came to the crunch, he showed the pragmatism and shrewdness that had made him such an astute political survivor. Maybe he had understood something else about the Pieds-Noirs.

He first attempted to quell the drive for independence by promising to modernise Algeria and work towards integrating it into France by bestowing on it the benefits of that status: modern technology, development, education, health-care etc. These were all nice ideas, but in practice they involved forced relocation of people from rural zones in which they were no longer allowed to live in for security reasons; they involved disrupting social patterns of life that had existed for centuries in a misguided zeal for ‘progress’; in short, it was ‘development’ on France’s terms, many aspects of which Algerians didn’t want. In any case, it was too little, too late. As McDougall has put it:

The metropole was thus at last imposing a solution, but as ever, it was a solution to the problems of twenty years earlier.

Even offers of a paix des braves, a sort of amnesty to those who had taken up arms against the state, were largely ineffective, and under pressure from outside (the Americans especially) and the growing prestige of the FLN on the international stage, De Gaulle began to give way. The problem was that, as he put out feelers towards offering some kind of limited recognition or autonomy, the settlers reacted with intense fury and accusations of betrayal towards the man they had thought would save them. Settler paramilitary organisations had been around for some years already, manned by ‘ultras’ who had been responsible for numerous atrocities towards Algerian civilians. Now, their violence intensified and involved elements within the army who felt they were being sold out, and several attempts were made to kill De Gaulle when he visited in 1960. Early 1961 saw the foundation of the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), the ‘secret army organisation’, by right-wing former army officers exiled in fascist Spain, and began a campaign of violence in Algeria designed to keep Algeria French.

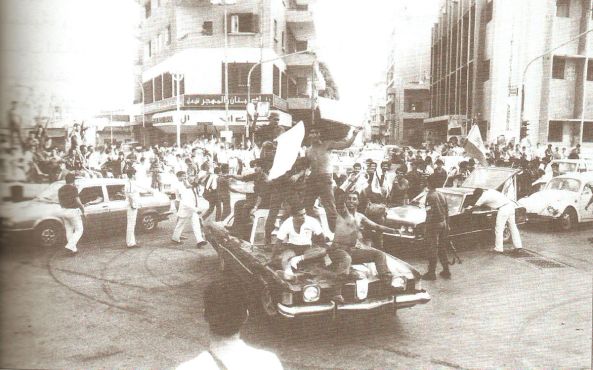

Thus, just as the army thought it had quelled the revolution, the country descended into a downward spiral of violence orchestrated by those who were determined to make sure that the French government offered no concessions that would alter their domination of the natives. This, of course, guaranteed that the crisis could not be defused and made independence inevitable. De Gaulle began to realise this and (probably even more importantly for him) that the Algerian problem threatened to stymie all his attempts to rectify the problems facing France itself in his new Fifth Republic. Another development also forced De Gaulle’s hand, which was in part a response to settler and OAS violence: namely, the mobilisation of the Algerian people. Whereas in the early days, the FLN had been a relatively small group of visionaries who often had to coerce the civilian population into co-operating with their strategy, by the end of 1960, tens of thousands of Algerians were demonstrating on the streets of Algiers, Oran and other towns, not just against the nature and abuses of French rule, but French rule in itself. French soldiers firing indiscriminately into the crowds and killing hundreds only hardened their hearts.

Nor was the violence confined to Algeria. In France itself, where the Algerian émigré community (by 1964, there were almost half a million Algerians in France) was an important source of funding and support for the FLN, protest marches took place, one of which was attacked by the police on 17 October 1961, enthusiastically joined by métro workers, firemen and passers-by. At least 120 (but possibly as many as 300) of these peaceful protesters were beaten to death or thrown in the Seine to drown.

Even after independence, a deeply-poisonous relationship between Algerians and the French occasionally erupted into violence. As late as 1973, the killing of a bus driver by a mentally-ill Algerian in Marseille sparked off a Summer of killing across the south in which thirty-two ‘Algerians’ (many of whom were French citizens of Algerian descent) were left dead, killed by French mobs, whipped up by a media which likened Algerians to a ‘vermin’ and ‘a plague’. Another aspect of this is the effect that large numbers of Pieds-Noir fleeing Algeria as independence became more likely had. There were about a million in 1960, of whom 800,000 more or less left immediately and another 150,000 in the years that followed, so that there were only about 50,000 of them by the end of the 1960s. These overwhelmingly settled in the south of France or Corsica, and many would go on to support the anti-establishment, far-right Front National of Jean-Marie Le Pen, which was founded in 1972 and support for which was strongest in precisely the areas where the Pieds-Noirs settled, disgruntled and resentful towards a French political establishment which had betrayed them, and likewise resentful towards the Arab emigrants in France, with whom they lived side by side, and whom they felt it was their birthright to lord over, which was now taken from them.

This was just another sense in which the poison of the Algerian war was seeping into the body politic of the ‘mother country’, and De Gaulle began to talk of the inevitability of ‘self-determination’ and an Algerian republic. A referendum was held in early 1961 which gave him permission to negotiate with the Algerian provisional government, and negotiations began shortly after. One result of this was an attempt by some of the more right-wing generals in Algeria to launch a coup, designed to remove De Gaulle and prevent the loss of Algeria. It had the opposite effect. De Gaulle went on television to appeal to the nation to stand by him, and in the end most of the army backed him. Having faced down this threat, serious talks with the FLN got underway near the Swiss border at Évian-les-Bains in May, and continued until March the following year, during what the violence of the OAS intensified, against both the FLN and French government targets.

One of the main sticking points preventing an agreement was the French demand, alluded to above, that they retain large areas of the Saharan interior, where oil had been found and nuclear weapons could be tested. The increasing brutality of the OAS (they blinded a four year-old child in an assassination attempt on a French minister in February 1962) undermined the efforts of the French to hold out in their demands, however, and in March a ceasefire was declared, with referendum called for April (in France) and July (in Algeria) to ratify the so-called Evian accords, granting independence to Algeria. The French agreed to hand over most of the territory, excepting small areas they could temporarily use for military bases and testing sites; they also secured preferential treatment when it came to trading for Algeria’s oil, as well as guarantees regarding both the rights of Algerian immigrants in France and those of the settlers in Algeria.

Algeria became formally independent on the 5 July, 132 years to the day the French invaded the country. This did not mean an end to the tragedy, however, and in many ways the worst of the killing was still to come. It seems a theme of grudging imperial decline (cf: the Belgians sabotage of the Congo before they left, and the British hasty withdrawal from India that resulted in horrific communal riots and mass killings) that the departing ruler likes to leave as much of a mess as possible behind them, and Algeria was no exception. This could be seen in long term effects, such as the fact that the French took with them the blueprints for the drainage system and refused to share them, so that the Algerian authorities would have to dig up half the city every time they wanted to fix a burst pipe. The more dramatic short-term effect was the flight of the Pieds-Noirs, reprisals towards those who had collaborated with the French, and a campaign of senseless nihilistic violence by the OAS.

Many of the provisions of the Evian accords as they related to protecting the rights of those French left behind in an independent Algeria were rendered obsolete by the speed of events. As noted above, about a million Pieds-Noir fled to France, having no faith in the promises made regarding their lives and property. They can hardly be blamed for scepticism, since events like the Oran massacre, where hundreds of settlers were massacred by mobs after independence, and the FLN (or indeed the French police) didn’t lift a finger to help them, cannot have inspired confidence. Over the Spring and Summer, over 3000 settlers disappeared. You would think the OAS would have seen the writing on the wall in early 1962 and given up, but quite the opposite. They ratcheted up their campaign, exploding over a hundred bombs a day and launching attacks on French police and army. They also sought to prevent Pieds-Noirs from leaving, and had hoped to provoke the FLN into breaking their ceasefire and thus wrecking the prospects of peace, but the FLN kept their discipline and obeyed orders not to retaliate.

It was this discipline and organisation that probably sealed their victory, but as noted, this discipline did not extend to preventing vengeful mobs from massacring civilians, both Pieds-Noir and those who had sided with the French in the war, the so-called Harki (from the Arabic word for a ‘war party’). The fate of the Harki is, in many ways, saddest of all. While the Pieds-Noir were allowed to migrate to France for protection, the French authorities were far less generous towards those Algerians who had fought for them over the past decade, and De Gaulle issued orders that they be prevented from leaving along with the settlers. Although some escaped with the help of sympathetic police and army personnel, the Algerian population took a bitter revenge on the Harkis, killing perhaps 70,000 over the summer, often torturing them beforehand. Much of this was done by the above-mentioned marsiens, who joined the independence struggle late in the day and were now especially brutal in order to signal their loyalty and zeal to the new regime.

That the FLN condoned, even encouraged, this, did not bode well for the future of the independent state. In September, Boumediène’s ‘army of the frontier’ marched into Algiers, and a new round of blood-letting got underway, as the new state sought to consolidate its power and eliminate threats from within, both rival factions of the independence movement and the remnants of pro-colonialist sympathy. But nothing could be more misleading than to portray a united, harmonious FLN now taking the reins of power. As is often the case, when they had a single enemy and objective to rally around, factional struggles could be laid aside in order to focus on the task in hand. Now that was achieved, rivalries and conflicts-of-interest began to emerge as the victors squabbled over the spoils. I have not spent a great deal of time in this post looking closely at the personnel of the FLN and those who would become the leaders of an independent Algeria, because in the next post we will look at these power struggles, as the FLN established a one-party state and the heroic early years of Algeria as a torchbearer for Third World liberation gave way to the stagnation of the 1980s and devastating civil war in the 1990s.

FURTHER READING

Charles Robert Ageron, Modern Algeria: A History from 1830 to the Present (London, 1991; first published in French 1964)

Martin Evans and John Phillips, Algeria : Anger of the Dispossessed (Yale University Press, 2007)

James McDougall, A history of Algeria (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Featured image above: soldiers search women in Algiers during the war of independence.