We have already looked in previous posts at the war in Afghanistan from its beginnings in 1979, beyond the Soviet pullout and into its civil war phase, up to the Taliban’s conquest over much of the country in 1996. This gives us, in a fair amount of detail, a good understanding of the heterogenous groups first fighting the Soviets in a loose coalition, and then each other, providing the background for the story we have to tell here, of another group which assisted in the jihad of the 1980s, those who volunteered from other countries throughout the Muslim world to help their Afghan brethren defeat the invaders. While these ‘Afghan Arabs’ (yes, the term belies the fact that these were not Afghans and sometimes not Arabs either, but it’s the term people use) were a small minority of those who fought the Soviet Union, and the importance of their contribution is debated (even bin Laden acknowledged that the war was won by ‘poor, barefoot Afghans’) their status and reputation was legendary among Muslims. There is another reason why they are a focus of interest, and that is in the widespread perception that Afghanistan provided the breeding/training ground for the internationalist strand of jihadism that would emerge in the 1990s, often (clumsily, I will argue) lumped together under the label of al-Qaeda.

This post will be an attempt to trace the participation of these non-Afghan fighters in the Afghan war, then look at their evolution as the war was winding down into something else, which will turn against the sole remaining superpower which had helped in the jihad against the Russians. Essentially, we will try and trace the roots of al-Qaeda, but it should be noted at the outset that looking into the genesis of al-Qaeda is a minefield. You quickly realise there are numerous different accounts of its early years, different opinions as to when it was ‘founded’ (if this word even has any real meaning here) and what we even mean when we use the term al-Qaeda (a word meaning, the ‘base’ or ‘foundation’ in Arabic). Rather than favour any single one of these accounts, I am going to try and synthesise what seem to me the more reputable of them, and by necessity keep things somewhat vague where there is absolutely no consensus on an issue.

So there is going to be a lot of ‘in the late 1980s’ and so forth in what follows, at least up until 1998, and the aftermath of the US embassy bombings in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, when something called al-Qaeda begins to emerge from the mists of obscurity in contemporary documents. I think it’s interesting, for a multinational organisation that some claim had existed from the late 1980s onwards, that I can find not a single reference to the name al-Qaeda in any of the major western newspapers until 1998, and the American president Clinton continued to use the term ‘bin Laden network’ for the group even after 1998. This is worth bearing in mind. If anyone out there has fluent Arabic and can do a text search of some database with all the major Arabic-language newspapers and journals, I would be very interested in seeing what the earliest reference to the ‘organisation’ they can find.

Before we get to al-Qaeda, however, it is important to remember that such an organisation did not exist during the war against the Soviet Union. The main organisation for funneling Muslim recruits and money into the country from outside was the Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), usually known in English as the Afghan Services Bureau. This was basically a guest house in Peshawar where Muslims from outside could stay on their way to the battlefield, receive training and indoctrination. It also acted as a publishing centre for theological works, primarily those written by the founder of the MAK, Abdullah Azzam, a Jordanian-Palestinian scholar and jihadist who was the ideological driving force behind the development of an internationalist and militant Islamist movement towards the end of the war, anxious that the momentum should not be lost and the foreign fighters disbanded.

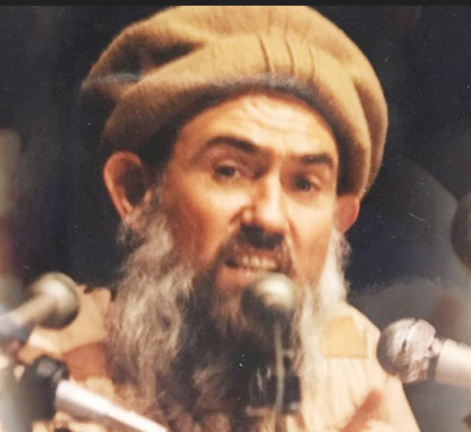

Although bin Laden is often represented as the mastermind behind these developments, in many ways this is anachronistic, a result of the prominent role bin Laden assumed in the 1990s. In fact, it was Azzam (below) who was bin-Laden’s elder mentor for much of the 1980s and some even credit him as coming up with the term al-qaeda al-sulbah (the solid base) in a magazine article he wrote, to refer to the revolutionary vanguard he argued was necessary to lead the Muslim world into rejuvenation and a resurrection of the Caliphate. While this might be an accurate explanation of the origin of the term al-Qaeda, this sounds a little bit too neat to me. Bin Laden himself is supposed to have said the name came about more or less by accident as a result of the term ‘base’ being used to refer to the Salafist training camps in Afghanistan, from which the name stuck. Either way, perhaps the best way to explain the evolution of this movement is to look a bit at the personal histories of the three figures so instrumental in its foundation and development: Azzam, bin-Laden, and Ayman al-Zawahiri, whom we have already met in part two of this blog.

Abdullah Azzam was born in what is now the West Bank, Palestine, in 1941. The 1967 war forced him and his family to flee to Jordan when he was twenty-five years old. He secured a job as a teacher in Jordan (he had already begun his life-long study of Islamic jurisprudence) but abandoned what might have been a relatively-secure (given the circumstances) existence to join the Fedayeen fighters against Israel. While, as we have seen in previous posts, the Palestinian resistance to Israel, led by the PLO was overwhelmingly secular (Hamas would not be founded until 1987), Azzam was unusual in that he combined his attempts to liberate his homeland with membership of the Muslim Brotherhood, at the same time developing militant ideas about reviving Islam that were at odds with the Brotherhood and had more in common with Salafist ideologies. Indeed Azzam found himself at odds with the PLO and was reportedly once brought before a tribunal, accused of insulting Che Guevara, to which he replied that Islam was his religion, and Che Guevara under his foot.

At this stage in the early 1970s, the left-wing umbrella-organisation, the PLO, was the only show on the road as regards resistance to Israel and, feeling such groups dishonoured Islam and neglected the broader cause of Islam in pursuit of Palestinian goals (although these should be central to a wider struggle), Azzam abandoned the fight and returned to his academic work in Egypt and Jordan. Having been fired for his continuing political activism in Jordan, he moved to a university position in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in 1981. It was not long before Azzam, who seems to have been a somewhat restless figure, began to feel disenchanted with those around him who, while they may have agreed on much ideologically, did little or nothing to put their ideas into action. The perfect opportunity was arising far to the east, however, where the war in Afghanistan was intensifying, and he perceived clearly that, while Palestine would always be the more important long-term goal for him, Afghanistan was the more immediate and pressing business at hand. He managed to get himself transferred to a university in Islamabad, Pakistan, from which he began to regularly visit Peshawar, the gateway for foreign jihadists into the Afghan war, a city he often referred to (here’s that term again) as al-qaeda al-sulbah.

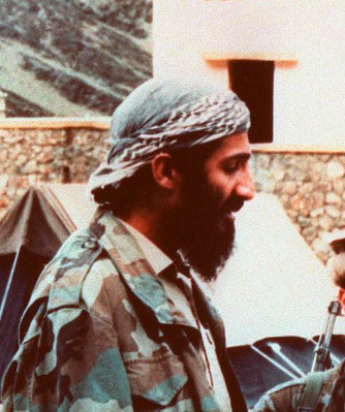

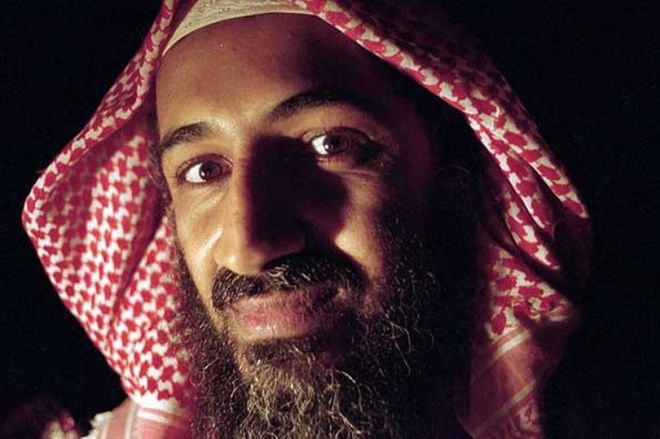

He met Osama bin Laden (below) on one of his many return visits to Jeddah in 1984. Bin Laden’s family owned the guest house where Azzam would stay, preaching and raising money for the cause in Afghanistan and the younger bin Laden was profoundly influenced by Azzam. At this stage, the jihad had the full support of the Saudi state, and Azzam’s call for an influx of Muslim fighters into Afghanistan had been endorsed by the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, effectively the seal of approval from the king himself.

Osama bin Laden was born in 1957, one of over fifty children of the Yemeni construction magnate Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden who died in 1967 in an airplane crash. His mother was a Syrian of Yemeni descent, Hamida al-Attas, who divorced Mohammed soon after Osama’s birth. It is sometimes claimed that she belonged to the Alawite sect, and even that she wasn’t really married to Mohammed bin Laden, being merely his concubine or ‘slave wife’, but this seems to be a fairly crude attempt to denigrate Osama bin Laden himself, and there is no evidence he was treated as a ‘lesser’ member of the extended family, which he surely would have been if this was the case.

Although there is no direct evidence for it, bin Laden’s first meeting with Azzam may have been in the late 1970s, as he attended the University of Jeddah to study business, and probably received religious instruction at the same time Azzam was working there. Most accounts of bin Laden in these years describe a hard-working, conscientious young man, modest almost to the point of shyness, and dedicated to his family, its construction business, and his religious faith. He worked for his father’s company, and not just in the token way the kids of rich people sometimes work, but actually worked on the sites, operating machinery, eating with the workers and earning a reputation for quiet generosity and for helping those less fortunate than himself while, although insanely wealthy, living a markedly austere lifestyle himself. There is no reason to doubt any of the many positive descriptions of bin Laden’s character that come down to us from those who knew him, especially those who have no ideological reason to eulogise him, and indeed have come under significant pressure to disparage and condemn him. There must, after all, be some reason for the tremendous personal loyalty he inspired in those around him, and we don’t need to buy into the simplistic image of an irredeemable monster that is peddled by the tabloid media. The overwhelming evidence is, unsurprisingly, that he had some admirable qualities, and this does not imply sympathy for his ideas or actions.

Another notable aspect of bin Laden’s character was the synthesis of word and deed. Like Azzam, bin Laden knew his theology and, like Azzam, knew that book learning alone was worthless unless acted upon. Conversely, he had tremendous respect for religious scholars, recognising that action without the wisdom to guide action alone was worthless too. If Azzam had been the kind of stay-at-home religious scholar that bin Laden would later criticise for not travelling to Afghanistan and joining the fight, their relationship would not have been as profound as it was, but his equal dedication to lecturing, writing and to fighting on the battlefield was one of the reasons the younger man admired him so much.

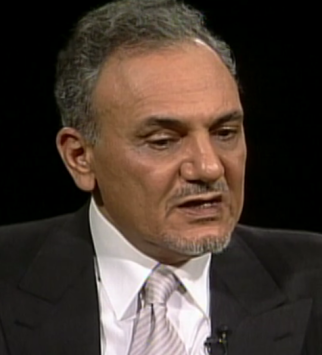

Although the precise date of his arrival in Afghanistan is debated, Osama bin Laden traveled to the war zone within months, perhaps weeks (some even say days but this is probably an exaggeration) of the war’s outbreak in December 1979. In these first few years. he acted mainly a conduit through which money passed from Saudi supporters to the Afghan Mujahideen. He recognised that his family’s financial resources, and those of other Saudis, were the greatest gift he could bestow on the cause at this juncture, and spent his time fundraising among his fellow Saudis and managing the disbursal of these resources back in Afghanistan-Pakistan. As time went on, however, he gradually assumed a more hands-on role as he developed a network of contacts, with the help of Azzam, and honed his military and organisational skills, taking a more and more prominent role in the operations of the MAK. For most of the 1980s, the Saudi government worked hand in glove with bin Laden and the Afghan fighters. Bin Laden’s main point of contact with the Saudi state was Turki al-Faisal, the son of King Faisal (see part 12), the head of its intelligence service, the Al Mukhabarat Al A’amah (General Intelligence Directorate) from 1979 to 2001. This is he in 2002 (for such an important dude, he seems to have been surprisingly camera-shy throughout the 1980s-1990s; I can find no images of him in that period whatsoever):

Bin Laden’s deteriorating relationship with the Saudi state in the early 1990s will be key to understanding his evolution from a jihadist against the communist enemy in Afghanistan, to declaring war on those governments in Muslim countries who he saw as inimical to Islam, and their chief enabler: the United States. Throughout the 1980s, however, he and the Saudi regime were rock solid in their support of the Afghans. You might want to return and look at part ten to refresh your memory as to the various factions fighting the war. Most of the resources from bin Laden and the Saudis were funneled into the factions of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, that is, those with the most fundamentalist and intolerant vision of Islam (and that is saying something, given the competition they were up against). Sayyaf, who had the closest links of all with Saudi Arabia, was the main facilitator in bin Laden building his ‘Afghan Arab’ unit, an objective which indicates something of a rift growing between bin Laden and Azzam from around 1987 onwards, as the two men began to grow apart on these subtle ideological differences.

Azzam had always a champion of promoting unity among the Ummah (the community of all Muslims) and wanted to disperse the non-Afghan volunteers out among the various Afghan groups as a way of fostering this. Bin Laden, however, was keen to found a separate unit of foreign fighters, believing this would better prepare them to return to their own countries after the war and wage war against the secular authorities there. There was also a perception that the ‘Afghan Arabs’ were being used by Afghan commanders as cannon fodder, although I have conversely read in places that there was an opposite concern, that the Afghans were treating the foreign volunteers as guests and refusing to put them in danger, depriving them of valuable combat experience. There was also a concern among Afghan commanders that the foreign volunteers were overzealous in seeking martyrdom, disrupting Afghan units with their recklessness. While prepared to die for the cause if necessary, Afghans were fighting a war to liberate their country and trying not to get themselves killed.

Another potentially-more troublesome rift was that Azzam championed Massoud (whom he described as the best Mujahideen commander) and this led to tensions with bin Laden and his allies. Perhaps the word ‘allies’ is putting it a bit too strongly. We should not exaggerate the differences he had with Azzam. Both men were concerned with preserving the unity of the Afghan forces and tried to avoid taking sides. Bin Laden would continue this attempt during the collapse into inter-factional fighting that followed the defeat of the communists. Azzam and bin Laden remained friends and comrades, and there is certainly no evidence to suggest that bin Laden was involved in the conspiracies that grew up among Azzam’s enemies and eventually led to his assassination in November 1989, only months after the Soviet withdrawal, but before the Afghan communist regime had been defeated.

But before we get to Azzam’s death, however, there is one more faction among the ‘Afghan Arabs’ that we should examine, that led by the Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri.

We have already briefly examined the early career of al-Zawahiri way back in part two when he was among the hundreds of Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) members rounded up and arrested in the aftermath of Sadat’s assassination in 1981. Following this, he was imprisoned and tortured in Mubarak’s prisons for three years, leaving Egypt upon his release in 1984, first for Saudi Arabia and then to Pakistan and Afghanistan, where he had already worked as a relief worker prior to his arrest in Egypt. It was here that he met Azzam and bin Laden. Al-Zawahiri was one of many members of EIJ who left Egypt during the years after Mubarak’s crackdown, as hopes for a religiously-inspired uprising of the people in their country were disappointed.

A potted history of EIJ might be in order here, seeing as they are going to be folded into the broader story of Salafi jihadism as it evolves in the 1990s. For the background to the Egypt of the 1970s in which EIJ had it roots, see part two. As we have seen, al-Zawahiri had already been involved in underground Islamist activity since the death of Sayyd Qutb in 1966. The individual who provided the catalyst for the formation of a jihadist organisation, however, was Muhammad abd-al-Salam Faraj (below left), an engineer and university administrator who wrote a widely-read pamphlet entitled The Neglected Obligation (in English sometimes translated as the ‘The Neglected Duty’, the ‘Forgotten Duty’ or variations thereof), which argued that, not only did the defense of Islam justify the taking up of arms against unjust rulers who were hostile to it, but that this was in fact a duty of all true Muslims. It was a key text in the development of modern jihadism and Faraj further argued that the ‘near-enemy’ (that is, hostile secular regimes in their own countries) were the enemy to be prioritised. An engaging speaker, Faraj soon attracted a cadre of followers recruited from his sermons in mosques. They included al-Zawahiri and, as fate would have it, an army lieutenant named Khalid Islambouli (below right).

Islambouli told Faraj about a military parade planned for 6 October 1981 which President Anwar Sadat would be attending. Hated by the Islamists for the oppressive secular regime he ran, this hatred had intensified since the 1979 peace treaty with Israel. Islambouli and other sympathetic army officers attacked Sadat on the appointed day, killing the president but failing to kill vice-president Mubarak, who would go on to rule the country for three decades. The ensuing trial gave Faraj and Islambouli an opportunity to promote their ideology from the dock, following which they were executed, no doubt satisfying a desire for martyrdom in the process.

As previously mentioned, many members of EIJ were imprisoned and rounded up in the period following the assassination, al-Zawahiri among them, but EIJ was not the only jihadist organisation active in Egypt at the time. Another branch (no doubt there was some overlap) developed in the 1970s called al-Jama’a al-Islamiyya (‘the Islamic Group’) particularly among students. Such Islamic groups had initially been tolerated, even encouraged, by Sadat as a counterweight to his enemies on the left. When he perceived that he had let the religious genie out of the bottle and turned on them, they hated him all the more for it. Some (including al-Jama’a itself) have claimed that they were responsible for Sadat’s killing, and personally I cannot conclusively say who did it. Both EIJ and al-Jama’a were inspired by the teachings of a blind religious scholar, Omar Abdel-Rahman (below), who would become particularly associated with al-Jama’a, and was considered by many to be its leader, perhaps more of a spiritual leader after his arrest and imprisonment in the United States in 1993, implicated in a supporting role for the bombing of the World Trade Centre in February of that year, but that is a story for another post.

The 1980s were a decade of dispersal and defeat for the Egyptian jihadists. Bearing in mind this is something of a simplification, many in the EIJ went to Afghanistan while al-Jama’a, once it had regrouped, became more synonymous with the war at home against the Mubarak regime. Loosely organised in the towns and villages among the poorest sections of society, the al-Jama’a was extremely difficult for the Egyptian state to prosecute. Having spent some time in jail after Sadat’s killing, Omar Abdel-Rahman was released in the mid-1980s and provided a talisman for the movement, even after he left for the United States in 1990. They set in motion a cycle of violence in which they provoked the Egyptian state (always happy to oblige) into more and more repressive measures, thus acting (hopefully) as a recruiting tool for their movement. In the early 1990s, hundreds of those considered blasphemous or hostile to their project were assassinated, the most famous example being the writer and critic of armed jihad, Farag Foda in 1992.

The armed campaign within Egypt began to have counter-productive results, however. While repressive measures may have alienated some towards the government, on the whole al-Jama’a‘s actions merely alienated the population towards it. In 1993, a bomb attack blamed on them killed seven and wounded twenty in a poor suburb of Cairo, an area supposed to be their natural constituency. Attacks on tourists damaged the heavily tourist-dependent economy, the most notorious of which was the killing of sixty-two people (all but four of which were tourists) at Luxor, which may have been carried out by a faction within al-Jama’a who wished to scupper attempts by others within the movement to declare a renunciation of violence.

The reason some within al-Jama’a were prepared to do this was because the movement had already been battered hard by the state, thousands of its members having been thrown in jail and the public mood turning against them. The Luxor massacre only intensified this revulsion, which in turn allowed the government to enact much harsher measures against them, which really went into overdrive following a failed assassination attempt on Mubarak in Ethiopia in June 1995. Responsibility for this attempts was also claimed by EIJ, and even bin Laden may have been involved. By this time, al-Zawahiri and bin Laden were in Sudan, and known to be funding and assisting EIJ members who had been exiled. What had happened in the interim to al-Zawahiri and his fellow Egyptians? According to Faraj’s creed, having killed Sadat, the people were supposed to rise up spontaneously and topple the existing order, replacing it with an Islamic state and the imposition of shari’a. When things didn’t pan out this way, and after having spent a few years in prison, many Islamists went to Afghanistan, al-Zawahiri among them. Here, they linked up with the foreign fighters’ being organised by Azzam and bin Laden, al-Zawahiri becoming a sort of counter-influence with bin Laden and no doubt a factor in his shifting away from his mentor and taking his own initiatives.

The Egyptians, many of whom were well-educated (doctors, lawyers, teachers, etc.) became known as the ‘brains’ of the operation and quickly rose to prominent positions in the non-Afghan units. As al-Zawahiri’s importance as an advisor to bin Laden grew, so the ideological fissures in the jihadist movement as a whole become more acute. Azzam had been a great proponent of Muslim unity, to the point that he disapproved of wars against other Muslims, even those regimes in Egypt and Algeria who had shown themselves hostile to Islamists. Azzam’s priority was the building of a new Islamic society based on Koranic models and the worldwide revival of Islam through defensive jihad. So, while in the long term they no doubt looked forward to a distant time when the whole world would convert to Islam, in practice they were not interested in aggressively spreading the religion, merely recovering to the fold of true Islam what they saw as areas that belonged rightly within it. It should be noted that although scholars call this ‘defensive’, it meant to people like Azzam and bin Laden, places like Andalucia in Spain and Mindanao in the Philippines.

In the question of who should constitute the enemy, the influence of Qutb was therefore far less marked in Azzam and, by extension, bin Laden, than in the case of al-Zawahiri and the other Egyptians, who vied for influence over bin Laden (who was, after all, the one holding the purse strings) as the Afghan war grew to a close. This contest culminated in a series of bitter disputes in 1989, as the al-Zawahiri faction accused Azzam of various misdemeanours, ranging from the specific (misappropriating funds) to the outlandish (that he was working for the CIA). Resentment at his support for Massoud and his closeness to bin Laden no doubt played a role too. Warned that his life was in danger in Peshawar and that he should leave town, Azzam ignored this advice and was killed (along with his two sons) by a roadside bomb on the 24 November 1989. Although the context in which I place this event here might suggest al-Zawahiri’s faction had him snuffed out, really pretty much anyone could have done it: al-Zawahiri, Mossad, the Iranians, the Pakistani ISI, the Afghan or Jordanian secret secrvices, you name it, they’re all suspects, and I’m not in a position to determine which of these claims is the more credible. I really do want to try and avoid flirting with conspiracy theories on this blog, so I will leave it at that. He was killed. We don’t really know who did it because the Pakistani authorities didn’t release any of the forensic evidence.

With Azzam gone, you might imagine that the way would now be clear for al-Zawahiri and the Egyptians to exert more complete control over bin Laden and his money, but by now, the Saudi had matured and was very much his own man. Although he would show influences of the Egyptian doctor in his thinking over the coming years, in many respects he would keep alive the ideological legacy of Azzam, especially in concentrating his mind, long-term, on the ‘far enemy’ and the transnational jihad which would be necessary to confront it. The Egyptians, on the other hand, may have fled abroad, but that does not mean they had given up the struggle against the ‘near enemy’ at home. This would be evinced by the 1995 bombing of the Egyptian embassy in Islamabad by EIJ, of which bin Laden reportedly disapproved. As already noted, there was the attempt to assassinate Mubarak in this year too, and in the early 1990s, an observer might be forgiven for thinking that the future of jihad lay in these localised national struggles in Egypt, Algeria, Chechnya, Bosnia, etc. and the attempt to build an Islamic state piece by piece.

We will look at some of these struggles in subsequent posts, because they are absolutely vital (although few in the west appreciate how important they were) to shaping militant Islam in the last few decades. As a general observation, the psychological effect of victory against the Soviet Union should be grasped. Bin Laden’s generation of Muslims was one that had grown up in the shadow of multiple defeats to Israel, the gloss had gone off Nasser’s secular nationalism and the idea that the Muslim world might regenerate itself by adopting the technological innovations of the west and imitating its culture. The pessimism that replaced these hopes had been deep-seated, but the Mujahideen‘s victory in Afghanistan was transformational, seeming to affirm the belief of young men like bin Laden that, instead of trying to copy the west, the way to regenerate the Ummah was to return to the fundamentals of Islam and the example of the prophet Muhammad.

Fighters came home from the glory of victory with their defeatism dispelled and full of hope for the struggle back in their own countries, and the expectation that the oppressed masses (and make no mistake, they were oppressed) would rise up against their corrupt secular rulers. But, as we have seen, in Egypt and elsewhere, this didn’t happen, and disappointment led some to turn towards the ‘far enemy’ or turn towards the civilian population in their own countries in bitterness (we will see a textbook example of this with the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) in Algeria). As popular Islamist uprisings failed to occur, and resurgent secular states turned the screw on the jihadists, it began to appear that Azzam and bin Laden had been right after all: transnational jihad against the ‘far enemy’, the sponsor of their repressive regimes, was the real solution, to confront the real threat to Islam at its source: the United States.

Whether al-Zawahiri and his allies were really thinking along these lines is debatable, however. It was likely pragmatic concerns as much as anything else that dictated they bend to bin Laden’s will as the 1990s went by. Desperately lacking funds, and in the aftermath of increasingly-successful repression by Mubarak’s regime, EIJ deemed it politic to hitch a ride on bin Laden’s project of building up a base for transnational jihad instead of everyone fighting their own individual battles against their respective secular enemies. In 1992, both bin Laden and al-Zawahiri were in Sudan, where they had been given sanctuary by the regime of Omar al-Bashir and the influential Islamic leader Hassan al-Turabi, who was responsible for inviting bin Laden and many other jihadists into the country, both for ideological reasons, and in the hope that some of the wealthier Arabs, mostly Saudis, would invest in the country, which was relatively poor (this was before the discovery of significant qualtities of oil in the late 1990s). We will discuss Sudan in a separate post, but just to note here that many regard al-Turabi as having been not entirely honourable in his dealings with bin Laden (Michael Scheuer, for example, who is very knowledgeable about bin Laden, although I would not always concur with his interpretations), accusing him of draining the Saudi’s bank account and then allowing him to be expelled from the country under pressure from the Americans, having spent a great deal of money to little or no purpose in the country.

What al-Zawahiri was running away from in Sudan is obvious. Not only was Egypt no longer safe for EIJ members, but Mubarak’s security services had their tentacles in all sorts of other countries too, and were getting increasingly effective help from the CIA now that the Americans no longer needed the jihadists to fight the communists on their behalf. Al-Zawahiri’s movements in the early 1990s are a bit mysterious. He traveled around a lot on forged passports. At one point he was arrested in Russia in 1996 and held in prison for six months, but they didn’t know who he really was and released him. Bin Laden’s whereabouts between the end of the Afghan war and Sudan are less mysterious. He had returned to Saudi Arabia a hero, his legend only being burnished by an injury he received at the Battle of Jalalabad in March 1989. He still enjoyed the stamp of approval from the regime and, for his part, appears to have been still been a loyal Saudi subject at this stage.

Tensions soon emerged with the Saudi regime in several areas. First of all, there was their meddling among the Islamist factions in Afghanistan. While bin Laden had tried to use his prestigious position to bring the various groups together in order to prevent a civil war (which would happen anyway) between Rabbani-Massoud on the one hand and Hekmatyar-Sayyaf etc. on the other. Turki al-Faisal, however, strove on behalf of the latter alone, thus perpetuating divisions and hastening the slide to war. Then there was South Yemen where, as we saw in the last posts, the Islamists were emerging as a force to be reckoned with, fighting against the attempts of the southern Marxists to reassert their independence. Bin Laden and other jihadists in Saudi Arabia saw this as a more-or-less identical cause to the one they had fought in Afghanistan: atheistic communists, and camped in the Arabian peninsula of all places. They therefore threw themselves wholeheartedly into fighting them, participating in numerous attacks and assassinations of socialist leaders in the 1990-94 period. To the horror of bin Laden and his followers, however, their own government supported the Yemeni socialists, because they were seeking to undermine Yemeni unity and weaken the northern regime of Ali Abdullah Saleh. For the first time, bin Laden came up against the realpolitick of the Saudi regime when they asked him to stop fighting the socialists in South Yemen. Appalled by this failure to fulfill their religious duty to expel the infidel, he carried on regardless.

But worse was to come, far worse.

On 2 August 1990, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Kuwait. There followed a six-month long standoff in which the United States and its allies (among them Saudi Arabia) demanded that Iraq withdraw or face an international coalition, which would indeed expel the Iraqis from Kuwait in January. The Iraqis let it be known that they would attack Saudi Arabia if they were attacked (which they eventually did) and the kingdom was on high alert, aware that its existing defense forces would be no match for Iraq’s. This was before Iraq was destroyed by two wars and a decade of sanctions; at this time, Saddam Hussein had built its army into a formidable military power, regionally at least. Bin Laden had been warning, both in letters and public talks, about the threat posed by Hussein (whom he regarded as a monstrous secularist) and these warnings had gone largely unheeded. His continuing loyalty to the House of Saud is evinced by his offers to use his family’s resources to construct defensive fortifications and raise a force of veteran jihadists from the Afghan war to man it.

The Saudi government rejected his proposal and, most shocking of all, requested the United States send a force to help defend the kingdom. This is an absolutely crucial moment in understanding the rest of Osama bin Laden’s life and career. Here was the Saudi rulers bringing infidels, armed ones at that, into the land of the holiest sites in Islam, which were supposed to be defended by faithful Muslims alone. Among the Saudi king’s titles is ‘Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques’. This was an egregious violation of everything bin Laden and his fellow fundamentalists held dear, and a shocking betrayal by those whose duty he saw it to uphold the strict Wahhabist conception of Islam he believed in. On top of all this, King Fahd secured theological justification for his decision from the Grand Mufti (the same one who had blessed the foreign fighter’s intervention in Afghanistan), Abdul Aziz bin Baz (below) for the move.

Up to this point, bin Laden had always deferred to religious scholars, even when their dictates seemed to be guided by the interests of preserving the House of Saud rather than the sanctity of Islam. This critique was implicit in the Islamic Awakening (Sahwa) movement, which bin Laden supported when he returned to Saudi Arabia. This was a peaceful activist group which sought to bring the regime into full compliance with Islamic law and curb its more excessive material excesses. To even suggest that the monarchy isn’t already in complete compliance with Islamic law is, however, deeply subversive in Saudi Arabia, and the movement was met by a mobilisation of theologians and scholars by the state. The establishment of American troops in the kingdom was the straw that broke the donkey’s back as far as bin Laden and his companions were concerned, but it should be remembered that it was only with the utmost reluctance that he ‘went rogue’. Henceforth, he publicly denounced these state-sponsored scholars as corrupt propagandists and his farm was raided by the security services, who disarmed his followers.

Bin Laden became an increasingly dissident figure in Saudi society, dangerous from the point of view of the state because of the respect he enjoyed from his leadership in Afghanistan. It would certainly have been tremendously destabilising to have imprisoned or executed him. It is sometimes claimed that they banished bin Laden in 1991, or even that they let him go on condition that he not direct his activities against them. The most plausible story seems to me, however, is that he escaped. Having had his passport taken from him, he managed to get one of his brothers to acquire a ‘one-time’ passport for him to wrap up some business in Pakistan, after which he promised to return. He never did. In 1994, he would be stripped of his citizenship and disowned by his family. After a brief period in Pakistan, he moved to Sudan where, as noted above, by the time he was finished he had lost a fortune in unprofitable business ventures and payments to the regime in exchange for the sanctuary he gave them.

By 1996, the only country to which he could turn for refuge was Afghanistan, by now coming under the rule of the Taliban (see part eleven), who were soon busy forcing women to stay home, banning music, blowing up Buddhist statues and generally cutting the country off from the outside world. The idea that the Taliban and bin Laden and his movement shared the same goals and ideology, however, is very mistaken (although seems to be widespread). While they gave bin Laden and his followers refuge, for reasons which we will examine in a future post on Afghanistan after their takeover, the Taliban had little interest in transnational jihad and were in fact concerned about the kind of trouble bin Laden’s activities might bring upon them. Rightly so, as it would turn out.

In 1996, Afghanistan seemed the only country where the dream of an Islam, assertive in the face of what it saw as an expansionist and hostile west, could be kept alive, but it was only barely kept alive. This is important when we come to the late 1990s and the beginnings of al-Qaeda and its attacks on the United States: the jihadists were in crisis, weakened and harried, their project having run out of steam after the failure to overthrow regimes in Egypt, Algeria and elsewhere. It is all-too-often forgotten in the wake of 9-11 and the blowing up of the al-Qaeda threat out of all proportion, that what was still being referred to as the ‘bin Laden’ network was in pretty desperate straits, hiding out in the wilds of Afghanistan in one of the few places were it might still have a chance of hiding from the U.S. war machine. Of course, this is not to say that they could not inflict damage on property and life. As the 1998 embassy bombings and 9-11 indicate, they certainly had the financial means, the manpower and the will to do this, but none of this mitigates the fact that militant political Islam, that sought to establish regimes based on shari’a, as a movement, was largely a spent force.

Knowing this, men like bin Laden and Zawahiri knew that only by somehow provoking the west into some serious atrocities against the Muslim civilian population could they breath some life back into their failed project. The only way to do this was to commit some atrocity of their own, big enough to get the American’s attention and ignite the kind of apocalyptic ‘Clash of Civilisations’ that they (in common with American neo-Conservatives) were hoping for. It is round about here that we have to start giving consideration to the ‘organisation’ we now call al-Qaeda which would attempt to ignite such a conflict. I place the word ‘organisation’ between inverted commas because some accounts give the impression that a group of that name, with an explicit and definable hierarchical structure, was founded around 1988 when Azzam was still alive, along with bin Laden and Zawahiri, and straightaway began to prepare the Afghan veterans for a coming battle with the United States. Things are far from being that straightforward.

Certainly, as we have already seen, Azzam was talking about something called al-Qaeda or ‘the base/foundation’ in the years prior to his death. It doesn’t necessarily mean that this was an organisation though, at least not from this early stage. You will sometimes see numbered amongst bin Laden’s early attacks on the United States, the bombing of two hotels in Aden, Yemen, where American soldiers were staying on their way to Somalia. There is, however, very little evidence for his involvement. It is likewise with the bombing of the World Trade Centre in 1993, in which his role was at most limited to a distant and tangential financial support for some of those involved, possibly. In the early 1990s, there is nothing resembling a structured international network of jihadists directed from a centralised leadership. That does not mean that the idea of creating such an organisation did not exist. It seems overwhelmingly likely that it did, and that the term al-Qaeda was meant to suggest this aspiration, the base, foundation or basis on which a real movement which could realistically take on the west might one day emerge. The name can be seen as a recognition that this was more of an aspiration or long-term project.

Exactly how long term is difficult to say. Fawaz Gerges, for example, argues that al-Qaeda in the late 1980s and early 1990s meant only a series of maxims, not an actual organisation. This is perhaps an exaggeration, but there is very little evidence it amounted to much more than that. One of the best assessments is that of Jason Burke, who I think has done the most authoritative work (in English at least) on this. By the late 1990s, he argues that:

…bin Laden and his partners were able to create a structure in Afghanistan that attracted new recruits and forged links among preexisting Islamic militant groups…

but…

…they never created a coherent terrorist network in the way commonly conceived. Instead, al Qaeda functioned like a venture capital firm—providing funding, contacts, and expert advice to many different militant groups and individuals from all over the Islamic world.

Jason Burke, Foreign Policy, No. 142 (2004), p.18.

So, basically, rather than resembling a limited company with a board of directors and a CEO, by the late 1990s al-Qaeda was more like a franchise, McDonalds or KFC, with a certain amount of financial and logistic support given to those jihadists who wanted to perform a deed regarded as faithful to their cause. At times, indeed, it would seem as if certain groups and individuals were acting independently and simply using the name al-Qaeda (and the same is true more recently of ISIS) to lend gravity to what are basically lone-wolf actions. In this sense, al-Qaeda and ISIS have borne more similarity to the Animal Liberation Front than any conventional paramilitary group, in that anyone can carry out an action (there is no leadership) in the name of the ALF as long as they follow some basic guidelines, among which it must be mentioned to their credit is that no-one should be harmed, and indeed the ALF have never killed anyone.

As I suggested at the start of this post, I am sceptical of claims that al-Qaeda existed in any meaningful sense before, at very least, the late 1990s. The bombing of American embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam on 7 August 1998 is a crucial turning point in this respect. It is only after these that the security services and the media start talking about something called al-Qaeda. This doesn’t even mean that the people who carried out the bombings thought of themselves as members of an organisation of that name, even at this stage. One of the bombers, Khalfan Khamis Mohamed, denied having even heard of anything called al-Qaeda. The most plausible explanation for al-Qaeda‘s sudden emergence (it seems pretty weird, after all, that you go from nobody talking about them to them being this international network of highly-competent militants, practically overnight) is given once again by Burke:

It was the FBI, during investigation of the 1998 U.S. Embassy bombing in East Africa, which dubbed the loosely-linked group of activists that Osama bin Laden and his aides had formed as “al Qaeda.” This decision was partly due to institutional conservatism and partly because the FBI had to apply conventional antiterrorism laws to an adversary that was in no sense a traditional terrorist or criminal organization.

Jason Burke, Foreign Policy, No. 142 (2004), p.18.

That is, in order to have any realistic chance of indicting and convicting bin Laden and other instigators of these acts, the FBI needed to work within existing laws regarding criminal conspiracy. These necessitated the prosecutors providing evidence of the existence of an organization, in order to prosecute its leader, even if that person could not be linked directly to the ‘crime’. Of course, they needed witnesses for this, to testify that bin Laden was indeed the one pulling the strings from his hideout in Afghanistan. Enter an obscure figure called Jamal al-Fadl. He is so obscure that this is the best picture I could find of him:

This is a court picture from the trial which began in February 2001 of those who had carried out the embassy bombings, and (in absentia) bin Laden, al-Zawahiri and others who had financed them. Al-Fadl was a Sudanese jihadist who had joined bin Laden’s network in Afghanistan in the late 1980s. He was apparently a senior member of the ‘organisation’ in the following years but grew resentful of receiving a smaller salary than others and embezzled around $110,000 from them. Having been caught, he then went around to various security agencies hoping to be given refuge and a reward for offering them information. Finally the American embassy in Eritrea took him up on his offer and he went to the United States in 1996. It was a case of being in the right place at the right time for al-Fadl. When, two years later, the FBI badly needed someone who could join the dots for them and help construct a picture of al-Qaeda as a complex and tightly-structured organisation, al-Fadl was ready and waiting to do the job for them.

He gave them exactly what they wanted, because he had every reason to exaggerate the complexity and scope of al-Qaeda. The same was true of L’Houssaine Kherchtou, a Moroccan who was involved in the embassy bombings and gave detailed evidence of the ‘organisation’ in return for immunity from prosecution and witness protection. This is pretty much ‘the evidence’ for the existence of an international terrorist organisation called ‘al-Qaeda’ having existed since the late 1980s, and it is deeply flawed. In the aftermath of the 1998 bombings, and even more so after 9 September 2001, the exigency of building a prosecution against bin Laden and co. had become a more important priority than the actual truth of what al-Qaeda was and how long it had been around. The problem is that the flimsiness of the evidence it was based on was forgotten and subsequent accounts have reported the findings of the trial as if it was solid primary evidence.

Once again, none of this is to deny the fact that some kind of a network clearly existed prior to 1998 (and likely for some years) that had as its aim the extension of the war to the United States. Bin Laden made this clear in a public declaration of war on the United States in August 1996, published in the London-based newspaper Al-Quds al-Arabi, making clear that he had shifted his focus on corrupt regimes like Saudi Arabia, to their main sponsor. There was also the well-attested creation of the ‘World Islamic Front’ in February 1998, a union of al-Zawahiri’s Egyptian faction of EIJ and bin Laden’s network (whether we wish to refer to it as al-Qaeda at this stage or not) along with a few smaller jihadist groups. The fatwa in question contained sentences like: ‘The ruling to kill the Americans and their allies — civilians and military — is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it…’ You get the drift: the kind of thing you would imagine a formidable anti-American jihadist organisation to declare.

Six months before the embassy bombings, however, these grand declarations were greeted in the west with the semi-indifference they probably deserved at the time. Even afterwards, in 2000, Fawaz Gerges, an expert in this field was writing:

Despite Washington’s exaggerated rhetoric about the threat to Western interests still represented by Bin Ladin [. . .] his organization, Al-Qa‘ida, is by now a shadow of its former self. Shunned by the vast majority of Middle Eastern governments, with a $5 million US bounty on his head, Bin Ladin, has in practice been confined to Afghanistan, constantly on the run from US, Egyptian, and Saudi Arabian intelligence services. Furthermore, consumed by internecine rivalry on the one hand, and hemmed in by the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt on the other, Bin Ladin’s resources are depleting rapidly. Washington plays into his hands by inflating his importance. Bin Ladin is exceptionally isolated, and is preoccupied mainly with survival, not attacking American targets. Since the blasts in Africa, not a single American life has been lost to al-Qa’ida.

Fawaz Gerges, ‘The end of the Islamist insurgency in Egypt?: Costs and prospects’, in The Middle East Journal, 54:4 (2000) 597-8.

Writing a year before 9-11, Gerges would appear to have been spectacularly wrong. But if you think about it a little more, it seems to me that he was essentially correct in all but one (dramatically important) respect. He failed to note that even a relatively small and battered group like this could still carry out an attack like 9-11, and rely on the reaction of the United States to spark off a decades-long war. The terrifying fact of the matter is that any dedicated small group with a pile of cash could have carried out 9-11: the ALF, ETA, the IRA, any of these paramilitary groups could, if they put their minds to it and weren’t bothered by mass civilian casualties. This was certainly true at that time, before the stricter security protocols that 9-11 brought about were introduced.

Nothing about 9-11 changed the fundamental geopolitical situation, but so traumatic was the event to Americans that they felt the need to believe that it ‘changed everything’. This compounded the tragedy. The American government’s response made sure it ‘changed everything’, not the attack itself, and this is exactly what bin Laden and his allies had been hoping for. Ironically, by declaring a ‘War on Terror’ against an amorphous network of desperadoes as if it was a coherent ‘army’, sophisticated and hierarchical, there is a good argument to be made that the United States brought such an organisation closer to actually existing. After 9-11, many jihadist groups started calling themselves ‘al-Qaeda in the something or other’. A glance through some of the names of these groups claiming to be branches of al-Qaeda (below) suggests they are actually more-or-less independent organisations seeking to claim some of the street cred which bin-Laden’s group acquired among jihadists from the exaggerated threat they were presented as after 9-11. Again, bin Laden was only to happy to be blamed, and presented as some kind of omnipotent and mercurial Bond villain.

Al-Qaeda in Iraq (2004)

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (2007)

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (2009)

Al-Qaeda in Somalia (2010)

Al-Qaeda in the Levant (2012)

Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (2014)

If al-Qaeda was a franchise, the American state department drummed up some great business for them.

It might be asked why they did this? To analyse the American military-industrial complex is beyond the scope of this post, but it’s pretty obvious to any impartial observer that the military, security services and large swathes of the political classes have a vested interest in keeping the public in a heightened state of fear from an external threat. Adam Curtis’ fantastic series The Power of Nightmares suggests that, with the apparent failure of ideology and dreams of a better future to inspire people politically, politicians have found a useable replacement in fear of a vague, implacable and irrational enemy, who ‘hate us for our freedoms‘. It should also be noted that the threat from Islam and Muslims begins to come to the fore just as the communist bloc is collapsing and they could no longer use that particular bogeyman.

Besides, this there is the extremely lucrative arms industry, which would collapse without a good war to keep it going (even better, one with a vaguely-defined and shifting enemy and no obvious objectives, just like the ‘War on Terror’, which can be extended indefinitely). This is worth $1.69 trillion a year (2016), a quarter of which ends up in the Middle East or North Africa. The US, the UK and France are responsible for around 70% of all exports of major conventional weapons to the Middle East. You can read more fun facts here. There are literally armies of people whose very livelihoods depend on the existence of something like al-Qaeda or ISIS. This included not only actual military or law-enforcement personnel, but a legion of academics (whose numbers have swelled since 9-11) who follow the money when it comes to the many postgraduates programmes and postdoctural fellowships which abound in the subject of terrorism and security. These, the very people we look to for authoritative answers about this subject, are institutionally disinclined to offer an alternative narrative to the one we were stuck with, even though it is highly dubious. They are no more likely to question it than a member of the theology department is likely to question the value of studying the bible, or someone in a business school is likely to critique capitalism.

Given all this, if we ask ourselves whether the world’s most powerful intelligence-gathering agencies misunderstood the nature of al-Qaeda or whether they deliberately distorted the picture to create an organisation where one hardly existed, the ‘exaggeration’ thesis seems more plausible than the idea that they got it wrong. This is not to say that there was no threat (clearly there was) or that these intelligence agencies knew about 9-11 beforehand or anything. Simply that the nature of the threat was manipulated in order to justify attacks on entire countries that had little or nothing to do with the atrocities bin Laden sponsored. Where, you might ask, does exaggeration shade into outright lying? Round about here:

Rather than go into the attacks on the World Trade Centre in 1993 and 2001, or the embassy bombings of 1998, I will examine them in some detail in a future post. Before we do that, however, we have to look at some of the conflicts that have been alluded to in this post, where the fight was taken up by jihadists in the 1990s to the ‘near enemy’ in Algeria, Chechnya and Bosnia, discrete national stories that have been forgotten in the haste to paint a picture of all-encompassing global conflict between ‘the west’ and ‘the Muslims’, but which, if anything, are more significant.

Featured image above: Eyes of Osama Bin Laden.

After the previous posts on the Afghan war, my intention was originally to examine the participation of foreign fighters in that war and their subsequent attempts to launch jihad in various other countries in the 1990s. I will defer this story for another post, however, as I wish first to backtrack somewhat to where we were after

After the previous posts on the Afghan war, my intention was originally to examine the participation of foreign fighters in that war and their subsequent attempts to launch jihad in various other countries in the 1990s. I will defer this story for another post, however, as I wish first to backtrack somewhat to where we were after